Michel Drapeau: Ghomeshi, rape in the military and what must change

Michel Drapeau says Lucy DeCoutere would have fared worse under a military tribunal

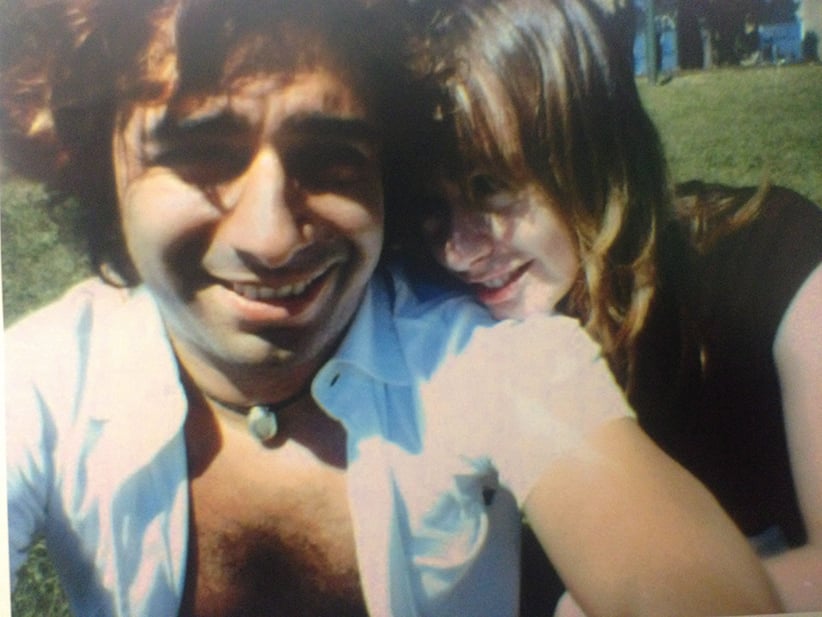

Lucy DeCoutere and Jian Ghomeshi and shown together in 2003 in this exhibit photograph from Jian Ghomeshi’s trial. (CP)

Share

Michel Drapeau is a retired colonel and an Ottawa-based lawyer specializing in military affairs. He believes the spectacle of the Jian Ghomeshi trial—particularly, the gruelling cross-examination of Ghomeshi’s alleged victims—will impede other victims from coming forward. Nonetheless, he says those alleged victims are far better off in the civilian judicial system than in the military equivalent, where they are deprived of certain basic rights.

Q: We have an interesting situation here, in that Lucy DeCoutere, the only witness against Ghomeshi to be publicly named, is a member of the military within a civil trial. In your opinion, how is that resonating within the military right now?

A: I’ve been part of this particular argument, that certain sexual crimes should be prosecuted before civilian tribunals. These crimes are not only tried by the military, but they are investigated by the military. If DeCoutere had gone through a military tribunal, she would have had to report her alleged assault to her chain of command. It would have been investigated by the military police, and prosecuted before a military tribunal.

It’s almost as though she’s better off that she was allegedly assaulted by a civilian.

I would think so. She has [an Ontario] Court judge who has probably had a significant amount of training and experience. And when she goes back to work, the people who were sitting in the courtroom, and the people judging her—they won’t be part of her work family. You can draw a parallel with Stéphanie Raymond, who was assaulted by her superior, a warrant officer, at the end of a Christmas lunch in 2011. She’d been out of the forces for almost two years by the time the military trial came. When it took place in the Quebec City armory, she was the only civilian in the court. The judge, the prosecutors, the defence, the court officers, the accused himself: all were military. The panel was all male in their late forties, all with a senior rank.

I think we need to say it first: the victim of any crime in a military procedure is excluded from the Victims Bill of Rights. Victims in most provinces and under federal legislation receive a whole bundle of rights, including right to information. None of them are available to military tribunals.

How do you think the civil system is in dealing with crimes of a sexual nature?

All victims of sexual assaults in the military should be referred to the civilian system. I’m not just talking about the courts, but the time when a 911 call is made. Normally, in the civil system, the police officers sent tend to belong to a special squad. They are trained to get the sort of information required in these types of cases. They get the Crown attorney involved. In the military, I regret to say, there are not enough to create a critical mass where there is a trained, competent efficient force on every base to do that. It simply doesn’t exist. It’s a disincentive for victims to come forward.

You mentioned that the cross-examination of the alleged victims in the Ghomeshi case will prevent other victims within the military from coming forward. But I wonder: witnesses need to be cross-examined. What would you have people do?

Nothing different. My only comment is, 75 to 80 per cent of victims, not just in the military but in among civilians as well, don’t report the crime. They have a variety of reasons. They have guilt. For others it’s a question of privacy, or they want to turn the page. They don’t want any more attacks on their dignity. Some of them will go through and retract. Only a very small number actually go to trial. Most alleged victims have never been inside a courtroom. They have no idea what they’re in for.

If the Ghomeshi trial has been of any use, it’s to open our eyes. In our system of laws, where the accused has constitutional rights, the defence attorney has an obligation to raise every issue that may create a doubt. That means a very robust and adversarial cross-examination. I don’t think many victims of sexual crimes are prepared for it.

Is this adversarial type of defence a good or a bad thing?

It’s somewhere in between. From a professional standpoint, if I were representing an accused, you certainly don’t want to sentence anybody who is not guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. I think there needs to be better preparation from the Crown. I think that any victims in these very sensitive areas from here on in should have their own counsel—not to represent him or her at trial, but to provide proper guidance, assistance and information as to what they’re in for. And if nothing else, to be saying to that person that they’re absolutely sure they’ve told everything there is to be told to the police and the Crown attorneys so that they’re not taken by surprise.