There’s a new strain of COVID-19. Will the vaccines work against it?

Vaxx Populi: The mutations identified in England affect the virus’s crucial spike protein, but so far scientists expect the vaccines will protect against the new variant.

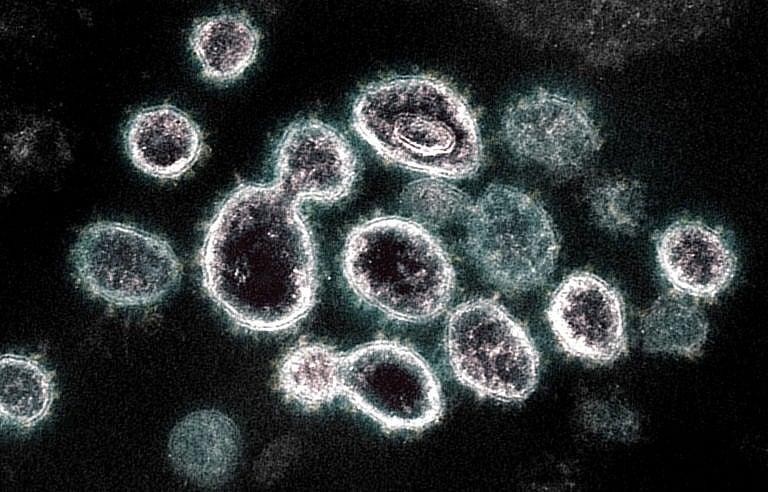

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. (Photo by: IMAGE POINT FR/NIH/NIAID/BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Share

On Dec. 14, British Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced that the government “has identified a new variant of coronavirus, which may be associated with the faster spread in the southwest of England.” Hancock said that more than 1,000 cases of this new-variant COVID-19 have already been detected in southeastern England, and similar variants have been identified in other countries recently, as well.

What we know about COVID-19 mutations

Finding a new strain isn’t unexpected, says Dr. Lynora Saxinger, an infectious diseases physician in Edmonton and assoc prof at University of Alberta. “Whenever a virus is spreading through populations it does accumulate some mutations, and you see strains emerge that can be different,” Saxinger told Maclean’s. Since being detected, the SARS-CoV-2 has accumulated one or two mutations a month around the world, the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium explained in a press release, with the vast majority of those genetic changes having no apparent effect in the virus.

RELATED: Can I get the COVID-19 vaccine if I have allergies?

That relative stability is what makes the coronavirus so unlike the seasonal influenza, says Saxinger: “Influenza literally changes its clothes. It has a whole wardrobe of outfits and it can swap them around every year, and then every year you’re trying to guess what it’s going to wear and making a vaccine for that.” In contrast, this coronavirus “doesn’t have a whole bunch of modules to swap in and out, and so far the spike protein antigens that are targeted by the vaccine don’t appear to be something that’s changing very much.” (A spike protein is what the coronavirus uses to enter human cells.)

Will the vaccines work against the new strain?

Because the mutations in the British variants do affect that crucial spike protein, there is concern the new vaccines may not work against this new strain. Researchers are investigating “at pace,” the U.K. consortium announced. Still, it stated, “There is currently no evidence that this variant (or any other studied to date)… will render vaccines less effective.”

RELATED: How realistic are government timelines for vaccine rollout?

Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist with the Federation of American Scientists, concurs. “We should assume it [the new strain] probably won’t [impact current vaccines] since the vaccine trains the body to develop immunity to the entire spike protein, and not just one part.” Dr. Lynora Saxinger is also fairly confident, saying, “I don’t think there’s any real big concerns that we’re going to have to come up with a new vaccine formula or repeat vaccination any time very soon.”

As Canada rolls out the country’s most complex vaccination project to date, Maclean’s presents Vaxx Populi, an ongoing series in which Patricia Treble tackles the most pressing questions related to the new COVID-19 vaccines. Send us a question you’d like answered at [email protected].