In Libya, Lockerbie bomber’s death brings sigh of relief, leaves questions unanswered

Maclean’s reports from Tripoli

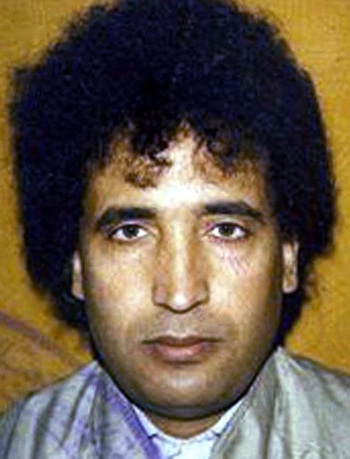

FILE This Thursday, Aug. 20, 2009 file photo shows Libyan Abdel Baset al-Megrahi, who was found guilty of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, center, being helped down the airplane steps on his arrival at an airport in Tripoli, Libya. Abdel Baset al-Megrahi, a Libyan intelligence officer who was the only person ever convicted in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, died Sunday May 20, 2012 nearly three years after he was released from a Scottish prison to the outrage of the relatives of the attack’s 270 victims. He was 60. (AP Photo)

Share

TRIPOLI — For most Libyans, the death from prostate cancer of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi, closes an embarrassing chapter–the only man convicted of the 1988 Lockerbie bombing, which killed 270 people, was a reminder of a past they would rather forget.

The circumstances of Megrahi’s long-anticipated death–when he left prison in August 2009 he had been given just three months to live–were a far cry from the hero’s welcome he received on his arrival in Colonel Moammar Gadhafi’s Libya.

Since Gadhafi’s overthrow in the third revolution of the Arab Spring, Megrahi and his immediate family had maintained a low profile and were increasingly ostracized, even by elders of their own tribe, the Megraha. They remained holed up in a luxury villa in Tripoli, lavished on them by the former dictator. Its thick walls kept out journalists eager to record one last interview with the ailing bomber.

Megrahi was reportedly worried about mistreatment by the rebels, and his family concerned that the new Libyan authorities might strike a deal to have him a returned to jail in the U.K. or dispatched to the U.S. for trial, as some U.S. lawmakers have demanded.

While dismissing any talk of extraditing him, the new government in Tripoli had started pressuring the dying Libyan intelligence officer to reveal information that would help them launch cases against senior figures in the Gaddafi regime. And that pressure was only likely to mount.

With Megrahi’s death, his cousin, Gadhafi’s spy chief Abdullah al-Senussi, remains one of the few persons alive who could shed light on the reasons for the Lockerbie bombing and exactly how it was carried out. Senussi has been under arrest in Mauritania since March, and is facing extradition to Libya, though he is wanted by the International Criminal Court in The Hague as well.

Megrahi, for his part, never pleaded guilty. In his last TV interview, filmed in December 2011, he once again insisted he had nothing to with the Lockerbie bombing. “I am an innocent man. I am about to die and I ask now to be left in peace with my family,” he said.

But while U.S. families reportedly remain convinced of Megrahi’s guilt, some British relations have cast doubt on the conviction. Dr. Jim Swire, who lost his daughter, Flora, has called for a comprehensive public inquiry, arguing, “I have been satisfied for some years that this man was nothing to do with the death of my daughter.”

Yesterday, his brother insisted Megrahi was a “scapegoat” for the old Libyan regime. “He has died and has left us with the feeling of injustice,” he told Agence France Presse. “Everyone knows that the Kadhafi regime blamed its mistakes on others.”

Scapegoat or not, nearly 25 years later, many of the questions around the Lockerbie bombing remained unanswered. Now, the man with most of the answers is likely the one sitting in a Mauritania jail.