The doomed 30-year battle to stop a pandemic

Paul Wells: For decades, researchers and officials obsessed with planning to stop an outbreak. Then along came COVID-19 and we were sitting ducks. What went wrong?

George W. Bush (Mark Wilson/Getty Images),

Donald Trump (Tasos Katopodis/UPI/Bloomberg/Getty Images), and

Trudeau (Courtesy of Adam Scotti/PMO)

Share

With hindsight, it’s hard to rewatch video and read the transcripts of Trudeau cabinet ministers, speaking to reporters on their way into and out of Question Period on March 10, without a feeling of dread and frustration.

One reporter buttonholed the Prime Minister as he headed into the makeshift Commons chamber in Parliament’s West Block. “On the subject of COVID-19 there are many Canadians coming back from overseas who are very surprised to see there are almost no questions at the airport, almost no posters. Is there laxity?”

“On the contrary,” Justin Trudeau replied. “We’re giving all the instructions necessary to Canadians to stay safe. We have enormous confidence in the efforts people are making because we’re giving them the necessary information. We’re following all the recommendations of experts and scientists.”

Less than a week later, horrified provincial governments in Nova Scotia and Alberta, and the mayor of Montreal, would start sending their own employees to airports to compensate for federal failure to move at-risk passengers straight to quarantine.

François-Philippe Champagne, the foreign minister, said he’d been on the phone that morning with his counterpart in Italy, which was being pummelled with one of the most severe coronavirus outbreaks to that point. That sure made another reporter’s ears perk up. “Are you considering something like Italy?”

“No, no, no, no,” Champagne said. “The situation in Italy is quite different than the one we have.” Was he being careful himself to avoid catching or spreading infection as he traveled? “I pay more attention,” he said, “but you know, it’s in my DNA to shake hands.”

Nine days later Champagne announced he was self-isolating after experiencing mild symptoms following international travel. Fortunately he tested negative for the virus. On March 10 Italy passed 10,000 diagnosed cases of the viral outbreak with 631 deaths. Canada would pass both those numbers within 31 days.

As Patty Hajdu, the health minister, was speaking, one reporter coughed into her balled-up fist. That sparked nervous laughter all around, and Hajdu reminded everyone that it’s safest to cough into one’s elbow and to stand two metres apart, which nobody in the Commons lobby was doing. “But I will also remind Canadians that right now the risk is low,” she added, twice.

A briefing note prepared that day for Hajdu and released later to the Commons health committee made precisely the same argument about low risk. The memo noted there were only 12 COVID-19 cases in Canada. But that wasn’t true. In fact there were 97 cases by March 10. An elaborate government apparatus was feeding the lead minister on a mounting public-health crisis information that was two weeks out of date.

March 10 was a Tuesday. On Thursday evening Trudeau was expecting the premiers in town for a first ministers’ meeting. A draft agenda sent to provincial premiers and obtained by Maclean’s set aside all of 25 minutes on Friday morning to discuss the coronavirus, followed by equivalent or longer sessions on February’s protester disruption of rail transport; economic competitiveness; climate change; northern priorities; and health care. A bewildered reporter called around: surely the agenda was changing as the crisis gained momentum? No it wasn’t, provincial sources said.

In the end there would be no meeting. Premiers started cancelling their flights. On Thursday Trudeau announced he was self-isolating after his wife Sophie returned from London with a fever. On Friday her diagnosis came back positive. The House of Commons passed three bills without reading them and adjourned indefinitely. The rest is the story of your own life, because that was when just about everyone in the OECD with the option to do so started working from home and avoiding the neighbours.

You will be disappointed or relieved to learn that, despite this grim little stroll down memory lane, this is not a story that attempts to blame Justin Trudeau for a global pandemic. The “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” to use the devious beastie’s formal name, had already jumped plenty of international firewalls before it started to wreak havoc in Canada. The most lurid example of system failure and leadership abdication, with a human cost proportionately far higher than in Canada, was taking place next door in Donald Trump’s United States.

The harsh beam of hindsight finds evidence of laxity is easy to spot all over. Question Period on March 10 was devoted, not to diligent opposition attempts to kick the tires on a federal plan to contain the outbreak, but to a dreary blame game over whose budget deficits were worse, Justin Trudeau or Stephen Harper.

Two days later Ontario premier Doug Ford would tell spring-break vacationers to “have fun” and “go away.”

Four days after that, New York City mayor Bill De Blasio, whose predecessors spent 20 years dealing with the consequences of sudden shocking mayhem, worked out at the Park Slope YMCA as though none of this were happening. A former top De Blasio aide, Jonathan Rose, wrote on Twitter that the mayor’s gym trip was “pathetic. Self-involved. Inexcusable.”

You don’t even need to focus on politicians to find examples of limited foresight. On March 9, the day before the ministers scrummed in Ottawa, the Globe and Mail ran an opinion article by Richard Schabas, who was Ontario’s chief medical officer of health for a decade and who, therefore, seemed to know a thing or two. The article’s headline was “Strictly by the numbers, the coronavirus does not register as a dire global crisis.” The tone of weary amusement continued throughout. COVID-19 was “The Incredible Shrinking Pandemic.” Schabas wrote: “Is COVID-19 a global crisis? Certainly for people who can’t add.”

Once the scale of the human, economic and social catastrophe became apparent, in the second half of March, it became sport for reporters to dig through the academic record to find examples of attempts by researchers and public-health officials to warn governments that this sort of thing might happen.

The New York Times reported on a months-long simulation by the U.S. department of health and human services—from January to August of last year—imagining a respiratory virus that appears in China, spreads by air traffic and arrives in the U.S. The simulation, code-named “Crimson Contagion,” found in-fighting among federal departments, brutal competition among states for medical equipment and sloppy implementation of social-distancing measures across jurisdictions.

The Globe and Mail found a “Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector” from 2006, prepared with impressive federal-provincial input and co-authored by Canada’s future Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam, and ran it under the headline, “Ottawa had a playbook for a coronavirus-like pandemic 14 years ago. What went wrong?”

And it’s definitely fair to ask about these unheeded early warnings. But what I found when I started reading the academic literature on emerging diseases is that there are simply too many of these simulations and draft plans to count. We’ll go over a few more before this story is done. Each reads in hindsight like a lost opportunity to build defences against calamity. Each was intended as warning and help by its authors.

As a distinct academic discipline, attempts to imagine and arm against unfamiliar new infections are about three decades old. The term “emerging viruses” was coined in 1990. Researchers and governments worked to learn about these unfamiliar threats, to develop global early-warning systems, and to develop an international rulebook for triggering government response. Authorities had plenty of chances to test their responses against nasty real-world surprises. SARS in Toronto in 2003. Swine flu in Mexico in 2009.

In the end it didn’t help much.

Kenneth Bernard is a retired rear admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service, which issues rank and uniforms to senior officials up to the Surgeon General. He ran pandemic preparedness operations under presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. “What you’re seeing now is not the result of massive intellectual input into appropriate response,” he said in a telephone interview. “What you’re seeing now is, ‘Oh my God. What’s going on? We’ve got to close everything down until we can figure this out.’ That’s not a sophisticated intellectual response. That’s a, ‘The ship is sinking, plug the hole’ kind of response.

“And it’s really important to see that. I mean, this is not what people would have planned to do.” Here he paused to chuckle bitterly. “Shutting down the world economy and putting millions of people out of work and dropping our GDP by 15 per cent is not anybody’s idea of a good plan. It’s what you do when you get caught off-guard and you have nothing else in your toolkit.”

***

In the decades after its founding in 1948 the World Health Organization concentrated on familiar, implacable diseases that had killed tens of millions of people over centuries, especially in developing countries: cholera, plague, yellow fever, smallpox. The tools often were, and remain, prosaic: vaccination, sanitation, mosquito and rat control. Progress was slow—disease always musters bigger armies than doctors can—but often measurable. In 1980 the World Health Assembly declared smallpox had been eradicated.

But there were new diseases. There always have been, as viruses mutate and human development transforms landscapes, giving old bugs new opportunity. But by the 1970s it was becoming clear that such events were happening more frequently. Rift Valley Fever killed hundreds in Egypt in 1977 and Kenya in 1998. Dengue, a mosquito-born virus probably thousands of years old, found huge numbers of new human hosts after the Second World War sent armies through the South Pacific. Hantavirus killed hundreds of U.S. and Korean soldiers in the Korean War.

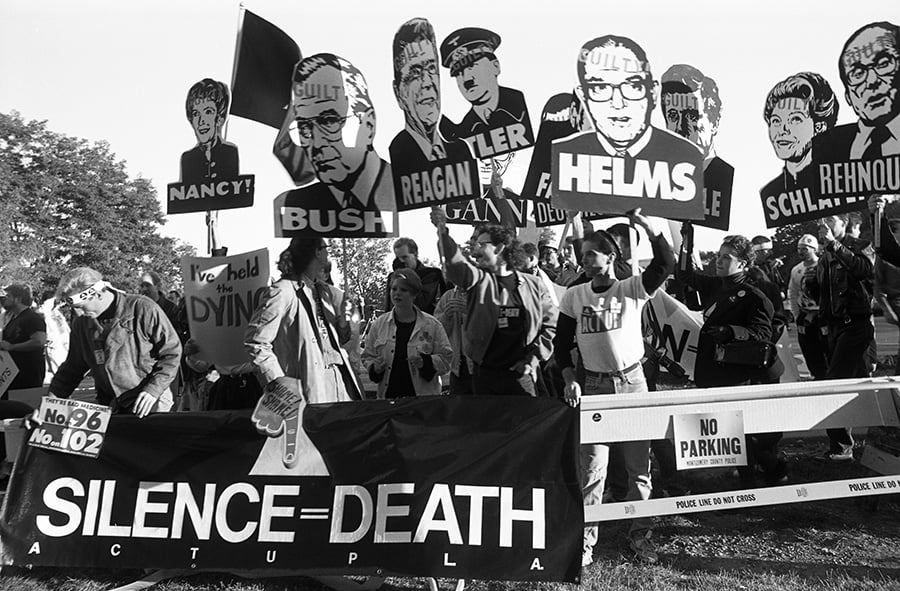

But the outbreak that changed everything was HIV, with hundreds of thousands of known cases of AIDS by the end of the 1980s, and a ballooning death toll, en route to more than 30 million deaths by the present day. As it spread through North America and Europe, HIV alarmed public-health officials and medical researchers, who started to wonder what contagions might be next.

In May 1989 the U.S. National Institutes of Health funded a conference on “Emerging Viruses: The Evolution of Viruses and Viral Diseases” in Washington D.C. The goal was to discuss reasons for all the new bugs, systems for spotting them early, and mechanisms for slowing their advance. But the opening keynote speech, by Joshua Lederberg, struck a prescient note of pessimism.

Lederberg had shared a Nobel prize for medicine in 1958 for showing that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. He had been a science advisor to U.S. presidents in various capacities since 1950, at a time when research and development had helped cement America’s role as, at least, one of two pre-eminent global superpowers.

“Some may say that AIDS has made us ever vigilant for new viruses,” Lederberg said. “I wish that were true. Others have said that we could do little better than to sit back and wait for the avalanche. I am afraid that this point of view is much closer to the reaction of public policy and the major health establishments of the world, even to this day, to the prospects of emergent disease.”

The conference’s organizer and chairman was Stephen S. Morse, who today is a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University. Morse coined the term “emerging viruses” for the sources of these new diseases. Sometimes the viruses really are new, the product of quick and constant mutation as these primitive squibs of genetic material make countless sloppy copies of themselves in their hosts. Sometimes the viruses are ancient but have simply found new hosts or new conditions to thrive.

“Surprisingly often, disease emergence is caused by human actions,” Morse wrote in a 1995 paper for the first issue of a new peer-reviewed journal published by the Centres for Disease Control, Emerging Infections Diseases. The faster human populations expanded into new lands and innovated new ways of building, farming and fighting, the more frequently new or unfamiliar infections appeared. “Perhaps most surprisingly,” Morse wrote, “pandemic influenza appears to have an agricultural origin, integrated pig-duck farming in China.” Waterfowl are often hosts to influenza viruses that can’t harm humans. Pigs can play host to both human and avian flu. Farming pigs and ducks together is an efficient way to pass new flu strains from birds to people.

But Morse, a flu specialist, was hardly blind to the threats from other agents. HIV had probably come from Zaire. Trouble could come from anywhere. “If we are to protect ourselves against emerging diseases, the essential first step is effect global disease surveillance to give early warning,” he wrote.

Government interest being spotty, it fell to the scientists to create the early-warning system themselves. In 1994 a virologist named John Payne Woodall, working under the auspices of the Federation of American Scientists—a descendent of the group that had launched the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb—launched a Program to Monitor Emerging Diseases, or ProMED. Woodall died in 2016. Stephen Morse was one of his colleagues in the launch of ProMED. The project began as a network of 60 hospitals and research institutions around the world that could spot new outbreaks, identify their likely cause, and spread the word.

It was a shoestring operation. In 1994 it wasn’t even obvious how the fledgling trap line would communicate. “The Russians had fax machines but they didn’t have money for fax paper,” Morse recalled in a telephone interview from New York, where he was isolating with his wife. “The Japanese wanted to use Telex.”

In the end the group decided to use email, a bold choice for a time when acoustic telephone couplers were the preferred method for connecting to the internet, if indeed an institution was connected at all. “Email was a very painful thing. It was almost a form of punishment.”

ProMED has never evolved far past its modest origins. But because it provides global reach, local analytical capacity in hundreds of locations, and is free and publicly available to all, it has remained a valuable sentinel network. It was notices on ProMED that first alerted the world to the 2003 SARS outbreak, and it was a posting on ProMED on Dec. 30, 2019—about chatter on the Chinese social network Weibo—that first spread word of a novel coronavirus, soon identified as the cause of COVID-19, outside China.

Early word of a new global infectious threat would prove useful again and again. But it would never be enough. “Global resources to emergency response,” Morse wrote in an 1996 paper describing the launch of ProMED, “are very limited at present.” Without response plans and the resources to implement them, populations would remain sitting ducks.

Getting governments to understand the danger took time. And as a very sturdy rule, each new government needed to re-learn the lesson.

You’ve already met Kenneth Bernard, the plainspoken former White House official. His training and interest in infectious disease made him uniquely qualified for a series of national-security jobs that, at first, he didn’t really understand. Through the 1980s he worked in the international viral-disease division of the CDC. He studied international public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the sort of school that could only exist in the former seat of a global colonial empire. He worked as a consultant to the Peace Corps and became, in his words, “basically the desk officer in charge of the U.S. relationship with the WHO.” He worked in Geneva at the U.S. mission to the UN, where the WHO has its world headquarters.

As that assignment was wrapping up, Bernard was told by Donna Shalala, Bill Clinton’s secretary of Health and Human Services, to report to the National Security Council across the street from the White House.

“At first, no one had much of an idea why I was there,” Bernard wrote in a 2018 Washington Post article. But eventually Clinton’s national security advisor, “Sandy” Berger, explained global health threats could kill more people and destroy more government power than most wars. To write disease off as a “soft” issue, Berger wrote, “is to be blind to hard realities.”

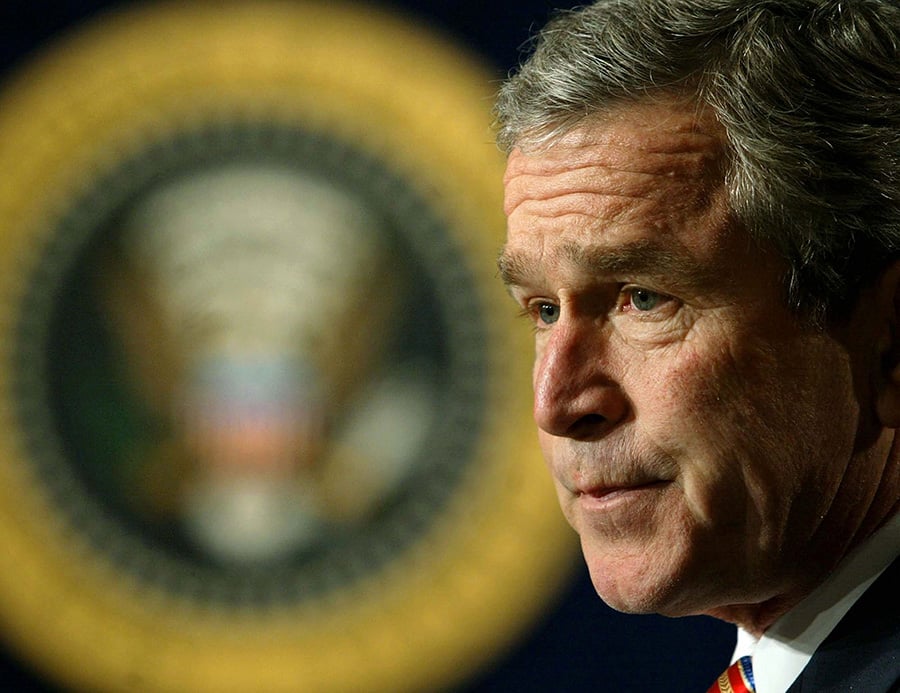

Obvious enough to Sandy Berger. Less so to his successors. In 2001 George W. Bush took office and shut down the Health and Security Office, which Ken Bernard had built at the National Security Council.

Bernard found work with Bill Frist, a heart and lung transplant surgeon who was serving as a Republican Senator for Tennessee. But he wouldn’t spend long in the wilderness, because in 2001 al-Qaeda terrorists slaughtered thousands at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and then somebody mailed anthrax spores all over Washington, killing five people.

Suddenly the connection between infectious disease and national security, sporadically visible to Clinton, became neon-bright to Bush. A hostile enemy could weaponize infection. Or an infection could kill hundreds of thousands without human help. Tom Ridge, the first secretary of homeland security, called Bernard back to the National Security Council where he built a big and well-funded office for health security.

So when the U.S. published its National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza on Nov. 1, 2005, under a dark-hued red-white-and-blue cover, it was with an opening letter from the president himself. “My fellow Americans,” Bush wrote. “Once again, nature has presented us with a daunting challenge: the possibility of an influenza pandemic.”

The Bush strategy was followed by an implementation plan and serious budgets to back it up. By 2007 Morse was able to write that, in contrast with “the optimistic neglect that often characterized past planning,” there was now real progress. The Bush administration provided funding and technical assistance to the WHO to improve surveillance. The U.S. example spurred other countries to develop their own pandemic plans. Work on vaccine production and antiviral medication, which might slow the spread of an infection, accelerated.

But researchers were starting to realize that if vaccines weren’t ready and antivirals didn’t work, the only way to blunt an outbreak would be what they called “nonpharmaceutical initiatives,” or NPIs: physical measures to stop the spread, including school and business closures, coughing or sneezing into elbows, and so forth. The CDC had a planning document on NPIs. It said they’d need to be applied quickly, targeted for greatest effect, and layered, which meant several such measures would need to be used simultaneously.

Still, the CDC recognized as far back as 2007, people wouldn’t like any of this. Widespread isolation would impose “significant challenges and social costs.” But that was no reason not to do them. Local communities would do them anyway, as they had during the 1918-19 flu pandemic. But left to their own devices, towns and states would implement NPIs in an “uncoordinated, untimely, and inconsistent manner.” That would cost the economy as much as a planned isolation strategy, the CDC wrote, but with dramatically reduced effectiveness.”

The other danger, perhaps even bigger, was that the Bush administration had launched a sprint but that Nature might prefer a marathon. What if the next outbreak wasn’t a year away, but a decade? “Perhaps most important of all is sustainability,” Morse wrote. “The public will eventually lose interest in an imminent threat that does not immediately materialize.”

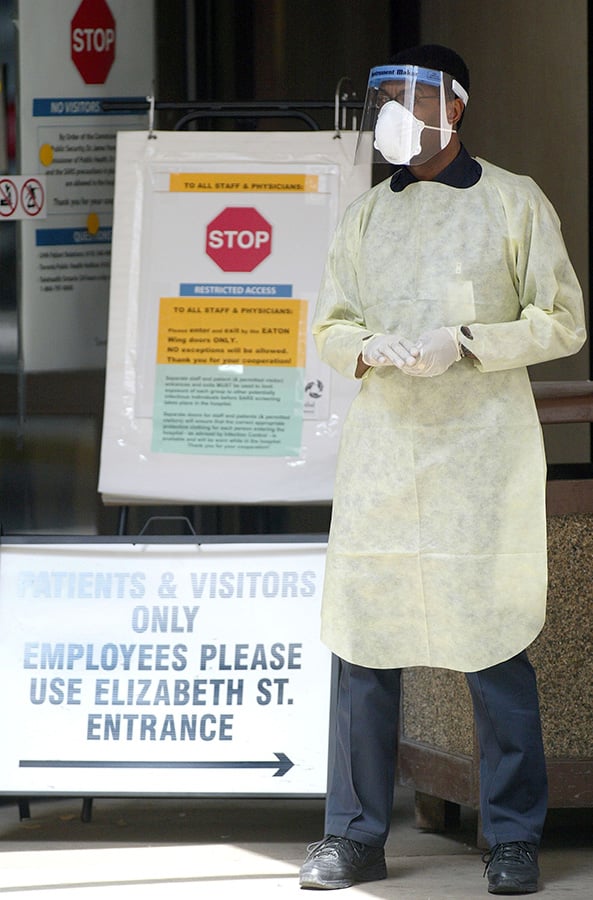

Canada was going through much the same thought process at the same time. Partly the post-9/11 ferment in the U.S. inspired emulation. But by far the bigger spur was a short, terrible outbreak that gave a generation of public-health physicians their reflexes: the 2003 SARS outbreak in Toronto.

SARS was a terrible ordeal, but in some ways an excellent foretaste of what was to come: an influenza caused by a novel coronavirus from China that spread through sneezes and coughs. City authorities in Toronto fought a mighty battle to contain the outbreak and the economic shock that resulted when the WHO advised against non-essential travel to Toronto. In the end the virus killed 44 people.

David Naylor was the dean of medicine at the University of Toronto when Anne McLellan, Jean Chrétien’s minister of health, appointed him to lead an inquiry into the SARS outbreak. He would go on to become the university’s president. Naylor’s report, “Learning from SARS: Renewal of public health in Canada” called for sweeping change to bolster Canada’s ability to respond to future outbreaks. Its centrepiece recommendation was the establishment of a new Canadian Agency for Public Health. That one got followed. The rest of the report, less so.

It’s not as though Naylor didn’t see it coming. In 1993, HIV led Health Canada to organize a meeting of Canadian and international experts on emerging infectious diseases at Lac Tremblant in Quebec. That earlier meeting had called for “a national strategy for surveillance and control of emerging and resurgent infections” and “the capacity and flexibility to investigate outbreaks.” A decade later, Naylor wrote wryly, “very similar recommendations are repeated in our report.”

The system Naylor and his colleagues envisioned would be robustly funded, ready at all times—“SARS has illustrated that we are constantly a short flight away from serious epidemics”—and constantly checked. In a federation like Canada, roles needed clarification or communication would break down. The report called for “integrated protocols for outbreak management, followed by training exercises to test the protocols and assure a high degree of preparedness.”

And for a while, the post-SARS momentum in Canada continued. Prime minister Paul Martin appointed Carolyn Bennett as Canada’s first Minister of Public Health, and by the end of that government’s short tenure, the Public Health Agency of Canada was ready to begin its work. One of its first products, in the fall of 2006, was the 550-page report the Globe and Mail reported on in March of this year, “The Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector.”

It’s an extraordinarily comprehensive document. Health administrators are told to scout long in advance for “non-traditional sites”—schools, gymnasiums, day-care centres—in case the health-care system is overrun. There are separate plans for Indigenous communities. There’s a planning checklist whose section headings stand as stark warnings: “The health care system may be overwhelmed.” “The usual supply lines will be disrupted.” “A pandemic vaccine may be unavailable.” And, for any reader who thinks this whole story is about what’s already happened instead of what might happen next, “The pandemic will occur in waves.”

But perhaps the most important words in the document appear in the fine print on the copyright page. “The Plan is provided for information purposes to support consistent and comprehensive planning… by governments and other stakeholders.”

It wasn’t enough to have a plan. Governments needed habits honed through practice and thorough self-evaluation. And over time, other, more familiar habits of government got in the way.

***

“I was struck when I was health minister and I would go to international meetings,” Jane Philpott, who was Justin Trudeau’s health minister from 2015 to 2017 said in a telephone interview. “Pandemic preparedness appeared on [the agenda for] every single international health ministers’ meeting. Or at least every one I ever went to. I went to G7, G20, Commonwealth, OECD. There was always about half a day spent on pandemic preparedness.”

Half a day is serious real estate in any international meeting. It suggests a very high priority on planning against a bad outbreak. And Philpott’s memory is accurate. The first item on the communiqué from the 2016 G7 health ministers’ meeting in Kobe, Japan is preparation for global public health emergencies.

At the G20 health ministers’ meeting in Berlin eight months later, ministers went through an elaborate simulation to play-act their responses to an outbreak. They were shown a video with archival footage of smallpox patients and Ebola crews in goggles and rubber suits. “Fear. Panic. Freefall,” a voice on the video proclaims. “Where will the next epidemic occur? What price will we pay?” A 40-page manual walked ministers through a set of decision-making exercises.

But then they all went home. When Philpott got back to Canada, she wasn’t pressed on contagion planning by MPs in the House of Commons or reporters in the lobby outside. “I don’t think Canada’s alone in being a government where, when the health minister comes back from the international health ministers’ meeting, there isn’t a great thirst among the media or anybody else to know what you talked about. Or what you’re going to do with what you learned there. So it’s not a body of knowledge that gets shared or resourced.”

This was a common thread in comments by everyone Maclean’s talked to with experience in public health: that over the long term there is never much political incentive to concentrate on planning for a contagious outbreak. There are moments of perceived danger, but an outbreak rarely comes when the authorities are expecting one. And eventually, for perfectly human reasons, attention flags, just as experts always warned it would.

Pierre-Gerlier Forest is the director of the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. Before that he ran the Institute for Health and Social Policy at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and the arms-length Pierre Trudeau Foundation in Montreal. And before that, he was Chief Scientist at Health Canada during the period when Martin and Harper were standing up the Public Health Agency of Canada. All along he has been an informal advisor to a succession of federal health ministers. He’s stayed in touch with the health department where he worked from 2004 to 2006, and as the coronavirus outbreak spread in February, he was reminded how unfamiliar many officials there were with the field of infectious disease in general.

“The bandwidth for science” at the federal health department “is quite narrow,” Forest said. “Nearly nonexistent at Health Canada and very narrow at the [Public Health] Agency itself. They didn’t know who they should follow on Twitter. They didn’t know which experts to connect to in the U.S. to know how they should react. They had nothing of the sort. And in part this is a capacity issue. It’s not their fault, it’s the fact that we have let the agency invest in very different activities, maybe since the start.”

A public health agency, after all, has a myriad of responsibilities. It normally helps lead the fight against obesity, smoking, poor nutrition and sedentary lifestyles—each a real threat to wellbeing, whether there’s a ravaging pandemic this year or not. PHAC has also been preoccupied for five years with a wave of opioid overdose deaths that pummelled Canada and the United States. Opioids have killed 10 times as many Canadians since 2016 as the coronavirus had, as of mid-April. The bug is killing people more quickly, but the drugs have had longer to do their worst. When Philpott appointed Theresa Tam, who is actually an infectious disease specialist, to lead PHAC in 2016, the only specific health challenge mentioned in the news release was opioids.

And the public-health agency isn’t even at the centre of most federal health ministers’ field of view, Forest said. “They tend to think when they’re appointed that they’re the minister of the Canada Health Act,” which enforces universality and public access in provincial health-care systems in return for federal transfer payments. “They think they’re taking charge of Canadian health care. And it’s very hard to get them to understand that their real mandate, their constitutional role, is public health.”

Justin Trudeau’s mandate letters to his three health ministers so far—Philpott, Ginette Petitpas Taylor and Hajdu—are public. None mentioned preparation for an infectious disease outbreak. But this is hardly a Liberal oversight. There was no mention of pandemic preparedness in the 2019 federal Conservative platform. There were a total of nine federal leaders’ debates in the 2015 and 2019 elections; journalists didn’t ask a single question about preparing for a global flu outbreak in any of them.

But of course they didn’t: there’s always something obvious going wrong right now that needs attention. As a military commander, Dwight Eisenhower used to divide tasks along two dimensions, how urgent they were and how important they were. The things that are urgent and important—country-wide rail protests, saving NAFTA—always threaten to swallow all of a government’s attention. The things that are urgent but less important can be delegated to more junior staff. The things that are neither urgent nor important can be ignored.

The things that are important but not urgent need to be written into a schedule, then guarded against encroachment. Too often they get swamped by today’s crisis. This helps explain why ambitious politicians in Canada rarely learn French even though they know it would improve their viability for national leadership. They’re too busy putting out fires. And it explains why federal officials so often seemed to be reading from an unfamiliar manual as they dealt with the coronavirus. It’s because they were.

I called Kenneth Bernard, the guy who ran disease security offices in the Clinton and Bush administrations, because of that 2018 article he published in the Washington Post. It ran after Donald Trump and his national security advisor, John Bolton, shut down the Office of Global Health Security at the National Security Council. Trump defenders say the capabilities of the office were simply shuffled elsewhere in government. People who actually worked with the office say it hasn’t been the same since. “We worked very well with that office,” Anthony Fauci, the distinguished epidemiologist who advises Trump, told a congressional committee in March. ”It would be nice if the office was still there.”

But Bernard’s point was that Trump wasn’t the first to shut down such an operation. George W. Bush shut down Clinton’s disease security shop, then opened his own after 9/11. Obama shut down Bush’s operation, then opened his own, under a biologist and career national-security civil servant named Beth Cameron, after 2012.

This Groundhog Day pattern of erasing earlier gains must be frustrating, but Bernard believes it’s human nature. “No one in the national-security realm likes dealing with public-health officials. They just don’t want to do it. If they’d wanted to do it, they would have become doctors or epidemiologists. But national-security people like bi-national, confrontational politics. They like chest-thumping, big-boy stuff. They don’t deal with little things like climate or human rights.”

Bernard asked me whether I’ve ever had serious surgery done. No, I said, but family members have. “All right. Take the personality of your big-time surgeon and tell them that they’re now going to become a pediatrician for six months. Can you imagine that personality sitting, talking to moms and screaming kids all day long? I can’t.”

He mentioned Bill Frist, the Tennessee Republican Senator he had briefly worked for. “Bill Frist, he’s a wonderful man. But, you know, he’s a surgeon. ‘I came, I saw, I cut, I cured.’ That kind of thing. And the same thing goes on with the whole community of national-security people. This isn’t their cup of tea. Planning for a pandemic is not a national-security person’s ideal way to spend the day.”

Sure, but most heads of government don’t have careers in national security behind them. Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trudeau—they’re civilians without a soldier’s chip on their shoulder about public health. Why can’t the pandemic experts hold those leaders’ attention either?

“Public-health people have for years ruined their own advocacy,” Bernard said. “And the way they did that was, in an attempt to be relevant, or to prove that they’re relevant, they would tell their bosses, ‘Look, these are complicated issues, these public-health issues. You need to have me in the room. I need to be the one who makes the decision. Because these are health issues, and you know, the average lawyer, politician, can’t make these important decisions.’ Which of course is bullshit. But the public health people kind of advanced that, because it made them more important in the room.

“What has happened is, when you take an issue and you tell this political person, the prime minister or the minister or whoever it is at the top, ‘This is a really important issue but you really can’t make the decision without my input because you really don’t understand this well enough,’ what do the people do at the top? They relegate the issue to a secondary place.”

“And the reason they do that is just human nature and psychology. ‘If it was important, I’d be making the decision. I’m the prime minister. Right? So if you’re telling me that I should not be making the decision, you’re telling me it’s not important.’”

This sounds like more of a systemic analysis than simply chalking it up to the President of the United States being in the wrong job, I said.

“Yes, well, the guy is in the wrong job,” Bernard said. “He did a terrible job in the first month of this. He closed down travel from China, which was good. He continues, in every news conference you hear, to take credit for doing that. The problem was, he assumed that would solve the problem. Which is idiotic. The fact is, there was no chance to stop the influx of coronavirus into the United States. You couldn’t just close travel from Wuhan, that’s ridiculous. Look what happened. The East Coast of the United States got its virus from Europe. They’ve already shown that. The big New York outbreak came from Europe, not from Wuhan.”

What, concretely, could governments have done better? Bernard, Morse, Forest and others said it comes down to testing and contact tracing in the early days of the outbreak, when it was still possible to track individual paths of infection and contagion.

In the U.S., Bernard said, “The lack of testing was almost a crime against humanity. I mean, it’s just unbelievable, the problem of delaying and getting adequate testing coming out of CDC. How that happened—everybody can go back and try to point fingers at who screwed up. But the fact exists that in the absence of widespread adequate testing like they had in Singapore and South Korea and such, there’s just no way to control this without locking everybody down like we’ve done.”

“What data are you going to use to determine whether somebody needs to stay home or not? Or has the disease or not? I’m just flabbergasted at the incompetence of the people who were charged with rolling out a test for this.”

Stephen Morse, who has been working to build a global early-warning and response mechanism for 30 years, is amazed by how little international coordination happened in the early days of the outbreak. “With SARS there was a fair amount of global cooperation,” he said. “It was under the aegis of the WHO but a fair amount was self-directed, countries spontaneously working closely together. This has completely gone out the window with this event. Every country, including European countries in the EU, was essentially on their own. This was a great surprise to me.”

Kenneth Bernard said he’s less surprised. “No, it’s completely predictable. This was like, it’s going to happen sometime. I hope it doesn’t happen soon. And I hope when it happens it’s not bad. But we’re not prepared.”

Right up until the real outbreak began last December, people who worried about outbreaks for a living were continuing to write their plans. On Oct. 18 at the Pierre, a luxury hotel across Fifth Avenue from Central Park in New York City, 15 global leaders from government, business and non-governmental organizations went through a four-hour role-playing exercise to simulate a global outbreak of a new coronavirus. The exercise, called Event 201, so thoroughly foreshadowed the current pandemic that it became popular later for conspiracy theorists to claim afterward that the event’s sponsors, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, had actually planned the catastrophe for evil purposes.

But paranoia isn’t actually needed here. In Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 movie Contagion, somebody asks Laurence Fishburne’s CDC director whether it’s possible to weaponize bird flu. “Someone doesn’t have to weaponize bird flu,” he says. “The birds are doing that.”

After the Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016, the World Bank and the WHO jointly set up a body called the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, to examine whether the world was ready for the next outbreak. The board, at arm’s length from both of its founding organizations, is led by former Norwegian prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland and by Elhadjh As Sy, Secretary General of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. It’s supposed to produce annual reports about pandemic preparedness.

The board’s first report came out last September and it was scathing. After three decades of reports and simulations, “current efforts remain grossly insufficient,” it said.

The people who spend their days studying the threat kept writing reports for political leaders. But a plan for deep cooperation among competitive jurisdictions against an unfamiliar infectious agent is of no use if it gets stuck in a filing cabinet. It’s like sending a Steinway piano and a book of Beethoven piano sonatas to the government every few years. If nobody studies and practices, that piano is never going to sound like Beethoven.

“Plans that don’t get funded and implemented and operationalized are shelfware,” Kenneth Bernard said. “They’re just term papers.”

Editor’s note:

We hope you enjoyed reading this article, and that it added to your understanding of the coronavirus pandemic in Canada.

But quality journalism is not free. It’s built on the hard work and dedication of professional reporters, editors and production staff. We understand this crisis is likely taking a financial toll on you and your family, so we do not make this ask lightly. If you are able to afford it, a Maclean’s print subscription costs $6 for the first six months — and in supporting us, you will help fund quality Canadian journalism in this historic moment.

Our magazine has endured for 115 years by investing in important stories and great writing. If you can, please make a contribution to our continued future and subscribe here.

Thank you.

Alison Uncles

Editor-in-Chief, Maclean’s