Why is the overwhelmed MSF in charge of the Ebola fight?

A ‘perfect storm’ of issues has left the world unprepared to deal with a worsening catastrophe

An MSF medical worker, wearing protective clothing relays patient details and updates behind a barrier to a colleague at an MSF facility in Kailahun, on August 15, 2014. Kailahun along with Kenama district is at the epicentre of the world’s worst Ebola outbreak. The World Health Organisation (WHO) revealed that the latest death toll from the Ebola virus in Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria had claimed more than1000 lives. Health Organisations are looking into the possible use of experimental drugs to combat the latest outbreak in West Africa. CREDIT: Carl de Souza/AFP/Getty Images

Share

Last March, Dr. Tim Jagatic, a family doctor with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) from Windsor, Ont., went to help fight the Ebola virus in Guinea, where the deadly hemorrhagic fever first broke out in December. A colleague told him, “We’re seeing the tip of the iceberg.” By July, when 660 people had died of Ebola, Jagatic was working in Sierra Leone. He told Maclean’s, “We are overwhelmed. Our resources are stretched to the limit. We need to double our staff, right here, right now.”

For many months, MSF made similar warnings and desperate pleas for international intervention in the West African Ebola outbreak. But it was like shouting into a void. MSF, a non-profit organization, has been left to do most of the patient care for people with Ebola. Since the epidemic began, it has treated 3,200 patients at six field hospitals, hired and trained 2,800 local people and deployed 248 international staff. The U.S., by contrast, has pledged 4,000 troops to help fight the outbreak; 348 have arrived. MSF says it will spend $66 million on the on the effort this year. Around 90 per cent of their budget comes from private donors. Canada has contributed $65 million to anti-Ebola measures, including $1.7 million to MSF.

Now, with the virus spreading beyond its control, the group is starting to buckle, according to Dr. Joanne Liu, a Canadian pediatrician and the international president of MSF. “It’s not possible for us to deploy more. This should not lie in the hands of a private NGO,” she says. “We used the words ‘unprecedented’ and ‘out of control’ in the spring. Nobody budged. If people had have been deployed right away, we would have prevented what is going on.”

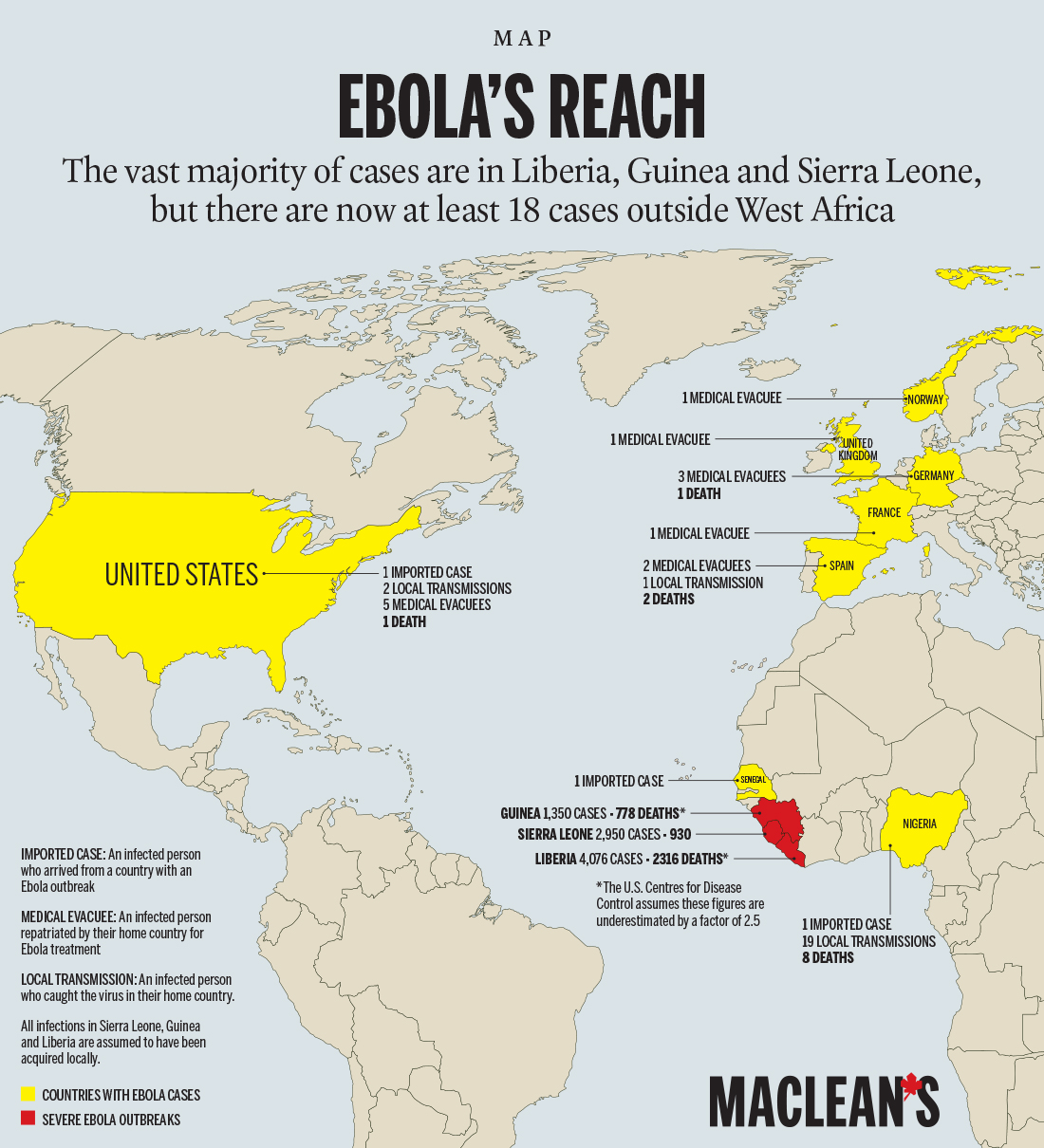

What’s going on is her idea of a worst-case scenario. Ebola is out of control in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone; official estimates say it has killed 4,447 and sickened 8,914 people. But the actual number of those infected is thought to be 2½ times higher, and it’s doubling every three to five weeks. Recent research puts the mortality rate at 70 per cent. To get it under control, about 70 per cent of the sick need to be protected from contact with others. As of late last month, as few as 20 per cent were being isolated in some areas. If the epidemic were to continue at the current rate, the World Health Organization (WHO) says there will be up to 10,000 new cases per week by December. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control predicts 1.4 million cases by early next year. Many others are dying of common ailments because hospitals are overwhelmed.

Ebola is now spreading to other countries, too. Unbeknownst to anyone, the virus was hiding in the liver and lymph nodes of Thomas Eric Duncan, 42, when he touched down in Texas from Monrovia, Liberia, on Sept. 20. His case revealed a lack of preparedness: When Duncan turned up in a Dallas emergency room complaining of fever, he was initially sent home. He returned two days later, much sicker, and died on Oct. 8—but not before passing Ebola to two nurses who treated him. In Spain, a nursing assistant who cared for two Ebola patients also tested positive and is gravely ill. Hers was the first case of person-to-person transmission outside of Africa.

Related:

- How safe are we from Ebola?

- An outbreak of red tape in the Ebola fight

- Everything you need to know about Ebola

While the virus can be contained relatively easily by Western health agencies, in West Africa, MSF has been completely overrun. “I’ve never had to turn away people infected with hemorrhagic fever and send them home because my centres are filled,” Liu says. “I’ve never had to open a centre for 30 minutes in the morning just to fill the beds of people who died overnight. I’ve never had to build a crematorium in the middle of my mission and burn 100 bodies in the same day. All my teams are telling us it is hell on Earth right now.” She finally felt that someone was listening after her remarks to the United Nations on Sept. 2, when she declared the world was losing the war against Ebola and pleaded for military and civilian aid. But, by Oct. 1, she was still unhappy with the progress.

The UN has launched a new mission (and a new acronym, UNMEER, the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response). It’s asking for $1 billion. Many countries have promised cash, supplies or medical staff. Canada has pledged two mobile labs in addition to $35 million in aid. But Liu called on the country to consider deploying DART, the military’s disaster response unit. Militaries can move massive numbers of personnel quickly, maybe fast enough to get ahead of the virus, and their people are organized, brave and easy to train, she says.

Britain is sending 750 troops to Sierra Leone; the U.S. has promised up to 4,000 to build treatment centres, mainly in Liberia. The New York Times reported earlier this month on delays plaguing the U.S. mission, with construction equipment breaking down and safety gear sitting idle in an airport hangar. Liu thinks if all the countries made good on all their promises within a month, they could turn the tide of the outbreak.

Operating largely in the background is the WHO, the UN public health agency. Why, many wonder, hasn’t it stepped up to relieve MSF? The WHO has a team of 200 in the outbreak zone, but its mission is to coordinate the various groups involved in the response, provide training, monitor the disease and get researchers together to solve problems. It is “a last-resort responder,” says WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic. “The truth is, the WHO does not have capacity to take on completely the treatment side. That’s why we’re appealing for the member states to see how we can get foreign medical help, because we recognize that MSF is very stretched to the limit.”

Various charities, including MSF, are essential in emergencies, but can create chaos without proper leadership and coordination, says Kelley Lee, a global health professor at Simon Fraser University. The WHO has failed to provide that leadership, she explains, for a “perfect storm” of reasons: an ineffective WHO African regional office, political and economic instability in the area and, most of all, because it doesn’t have the money it needs to do its job. The WHO’s regular budget has promised “zero real growth” since the 1980s, only increasing spending to account for inflation. It tightened its belt further in the late ’90s and froze the budget in absolute terms.

Lee puts the majority of the blame not on the WHO, but the rich countries that fund it. They want to control where their aid dollars are spent, so they use their own agencies and, increasingly, place conditions on the money they do give to the WHO. Seventy-seven per cent of the agency’s $4-billion program budget comes from voluntary contributions earmarked by donors, up from 49 per cent in 1997. The West hasn’t really felt the effects of the WHO’s money woes. But, once in a while—and this is one of those times—the consequences are clear. “Outbreaks are reported every week. Amid limited resources, decisions must be made on which can be left to burn out. [Past] Ebola outbreaks have been deadly but contained. There wasn’t an expectation that this would become a public health emergency,” Lee says.

With international help slow to arrive, more and more health workers are felled by the virus and the emergency gets that much worse. No one illustrates this better than Nancy Yoko. She spoke to Maclean’s in early August, just after she took over as head nurse of the Ebola treatment unit at Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone. The previous nurse in charge had died of Ebola. The hospital was filthy and chaotic for months, and more than 20 staff died in a short period before MSF and the WHO stepped in to help establish basic infection control. Yoko was a commanding presence in a deteriorating situation. She stomped around the treatment unit in her rubber boots and scrubs, barking orders. She would also sing and pray with her patients and impatiently declare, “I’m okay, I’m fine, I’m safe,” to anyone who inquired about her health. Yoko believe she was safe from Ebola; she was trained in infection control and constantly washed her hands with chlorine. In her interview she said, “We’ve lost a lot of our colleagues and friends. I will not catch it, and I will stay in this hospital until we get Ebola finished in this country. I have faith.”

After working 14-hour days continuously since May, Yoko caught the virus and died in less than a week. On top of the typical fever, pain and profuse vomiting, she was confused and delirious near the end.

It’s too late for Yoko now, but MSF president Liu is hoping for a game-changing vaccine that will protect health workers and others at risk. That will take many months, and there’s no time to wait. In the meantime, health authorities are sprinting to catch up with a virus that has outrun them, so far, by miles.

-with a file from Jo Dunlop in Sierra Leone