The Canadian judge who keeps the Olympics clean

Former sprinter Hugh Fraser moonlights as an adjudicator with the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Rio

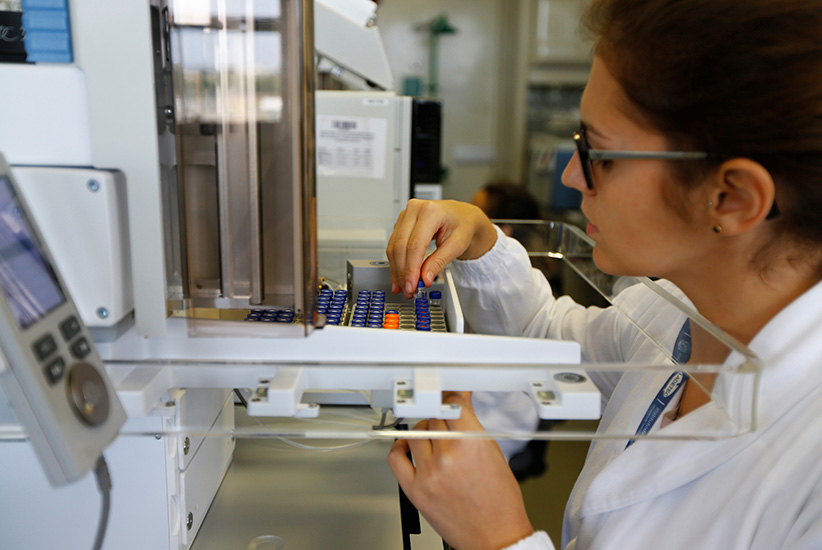

A woman works at the Brazilian Laboratory of Doping Control during its inauguration before the 2016 Rio Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, May 9, 2016. (Ricardo Moraes/Reuters)

Share

The call can come at any time. Day or night. Last week, it was while Hugh Fraser sat in the stands with his wife and daughter watching the heats for the men’s 100 m. But after two Olympics and two Commonwealth Games serving as an adjudicator with the Court of Arbitration for Sport—the final hope for athletes who run afoul of sports’ rules and regulations—he is used to it. The lawyers must be “Faster, Higher, Stronger,” too.

In 1976, Fraser represented Canada as a sprinter at the Montreal Games, competing in the 200 m and 4 x 100-m relay. (A hamstring injury kept him out of the individual 100 m, where his personal best was a still-respectable 10.10 seconds.) Turning pro wasn’t an option in those days, so afterwards, he hung up his spikes and went to the University of Ottawa law school. He became an athlete’s advocate, then served as counsel for the Dubin Inquiry into the Ben Johnson steroid scandal. Since 1993, Fraser has been a judge at the Ontario Court of Justice, overseeing criminal trials.

Atlanta 1996 was his initial lawyers’ Olympics. The Swiss-based CAS, as it is known, decided it needed on-site expertise at the Games and asked him to join its first ad-hoc court. The disputes to be ruled upon were sometimes petty—a fight over who should be the flag-bearer for a very small Olympic team, the athlete or the coach. (Sensibly, the arbitrators sided with the competitor.) They were sometimes life-altering. A swimmer tested positive the day before her race. The hearing began at 11 p.m. By 2 a.m., there was a ruling—that an eligibility* violation had been inadvertent. “At the end, we said the result was that she was in. They had to go knock on her and tell her, by the way, your heat’s at 9:30,” says Fraser. “Ultimately she went on and won the final.”

So far, Rio has proven to be “much, much busier,” than the other Games he has been involved in, says Fraser. Not necessarily because there have been more positive tests—he can’t speak in specifics about his cases, and many of the findings and names of the athletes involved are never made public, he notes—but because the CAS has broader responsibilities. The ad-hoc court now handles appeals of positive re-tests from past Games, too—a task that used to fall to the International Olympic Committee—as well as all the fallout from the decision to ban many of Russia’s athletes due to confirmed or suspected participation in a state-sponsored doping program. As such, the CAS brought 18 arbitrators to Rio instead of the usual six, and split the court into two divisions—one handling things that have happened in Brazil, the other the problems that arose elsewhere. Their rulings are based on Swiss law and a codified set of sports regulations, but the process is familiar enough for judges and lawyers from all over the world to participate.

As with his job back home, Fraser strives to keep an open mind. From his own past as a sprinter, he knows that Olympic cheaters have been around for a long time. “We used to joke about it,” says the still trim 64-year-old. “You’d look at the other athletes in the village and you knew. It was common conversation even at that time.” But sometimes, the doping positives really are the result of an innocent mistake. “I think there are some sad cases where people are taking supplements, maybe a hundred different vitamins or whatever, and there’s four of them that have been tainted.” It’s a system that needs to be flexible enough to deal with all of the extremes, from government spies switching out bottles of urine, to the athlete that takes bad bee pollen or ginseng.

The old athlete bristles a bit at the distrust that some of the public and media now have for record-setting performances. “I have these conversations with people I meet all the time. They assume these athletes must be on products. I cheer because I am a lifelong sports fan,” says Fraser, whose son Mark, 29, is a defenceman for the Edmonton Oilers “I ask, ‘Do you watch hockey? Do you watch football? Do you watch baseball?’ You know that not 100 per cent of those players are clean. It exists in all sports. Why have that extra layer of cynicism for the Olympics?”

Are Olympians cleaner than the pros? Yes, Fraser maintains. “Not because Olympic athletes are special, but because of the efforts to tackle it.”

There will always be cheaters, he says. What’s important is that the rest of us don’t accept it without a fight.

CORRECTION, Aug. 23, 2016: This story originally reported on a 1996 Court of Arbitration for Sport ruling that disqualified a swimmer for doping. In fact, the swimmer was ineligible for qualification due to late registration for the Olympics.