The making of Penny Oleksiak

From 2016: At nine Penny Oleksiak could barely swim. At the Rio Olympics, she won four medals, set one Olympic record and five Canadian records. Oh, and she’s just getting started.

Penny Oleksiak. (Photograph by Gabriel Rinaldi/Redux Pictures)

Share

Penny Oleksiak dips her hand into her red Team Canada backpack and retrieves four wool work-socks. Put aside the question of what kind of person brings winter foot-wrappers to the Summer Olympics, and focus instead on what’s inside them. Grabbing the green and yellow ribbons, she pulls the medals out one-by-one, laying the two bronze on her thighs, then the silver, and finally gold.

She drapes them around her neck. It’s the first time she has worn all four at once. “They’re so heavy!” she exclaims. The Rio baubles weigh 500 grams each. As she walks across the room they clink together, making a sound like wind chimes.

The Maclean’s photographer wants something iconic. He grabs his phone and shows her that picture of the great American champion Mark Spitz, with his cheesy moustache and seven golds from Munich 1972. I ask if she knows who Spitz is. “Not really,” Oleksiak admits with an embarrassed little laugh. “But I think I’ve seen the photo.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”2016MedalCount”]

The 16-year-old Torontonian can be forgiven for not knowing swimming history: She’s been too busy making it. Oleksiak finishes her first Olympics, which was also her first major international meet, with the most medals ever won by a Canadian at a single Summer Games. Her gold in the 100-m freestyle was the country’s first in the pool since Mark Tewksbury’s backstroke win at Barcelona ’92. The bronze she won along with her teammates in the 4 x 100-m free relay on the Games’ opening night, is the first swim medal by Canadian women since Atlanta 1996. She and Taylor Ruck, another barely-16-year-old Canadian relay swimmer, became the first Olympic medallists born in the 2000s. With Oleksiak leading the way, adding a silver in the 100-m butterfly and chipping in for another bronze in the 4 x 200 free, Canada’s swim team left Rio with a total of six medals. That’s two more than the country won in the pool over the previous three Summer Games combined.

Still, ask Oleksiak what the biggest highlight of her Olympics was—standing on the top of the podium as “O Canada” played, or getting a shout-out from Drake on Instagram—and she is legitimately torn. “It’s kind of hard to choose. Because Drake reaching out to me means a lot. He’s such a Canadian icon and there’s a lot of kids that look up to him,” she says. “But winning the gold means a lot to me too.”

Oleksiak swam nine times in Rio, setting one Olympic record and five Canadian records in the process. Winning four medals resulted in lots of late victory ceremonies and press conferences, too-wired-to-sleep nights and early-morning media commitments. She stifles a yawn, and admits that she’s looking forward to getting back home, where she hopes to “lay low” and enjoy what’s left of her summer. (Given that she’s the odds-on favourite to carry Canada’s flag in the closing ceremonies Aug. 21, her departure is likely to be delayed.) She wants to start in on some driving lessons, and figures that her mom and dad, Alison and Richard, owe her a dog, since her big brother Jamie, now a member of the Dallas Stars, got one for making the Canadian World Junior hockey team in 2012.

She’s heard that someone is planning a parade for her and the other Olympians from the east end of Toronto, and there’s talk that she might get the key to the entire city, but she’s not sure what else is in store. She has a newly acquired agent, who is working with her mom to sift through whatever endorsement offers come her way. Will her life be different from now on? “I’ve thought about it a little bit, but I don’t think it’s changed too much,” she says. “I’m just going to go home and try to live my life normally, I guess.” Before leaving for Rio, she went shopping at Lululemon and got turned down when she asked for a discount because she was a member of Team Canada. Now there’s a giant billboard with her face on it alongside the Gardiner Expressway in downtown Toronto.

There is one big obligation in her immediate future—a math exam that she put off in the spring so she could concentrate on training. Her face falls when she’s reminded of it. “I actually talked to my mom about it today. I think we’re going to hold off on it,” she says, hopefully. “I don’t want to study. I just want to chill out. I don’t want to do my exam. I’m just going to try and avoid it.”

Canada’s best-ever Summer Olympian has yet to finish Grade 10.

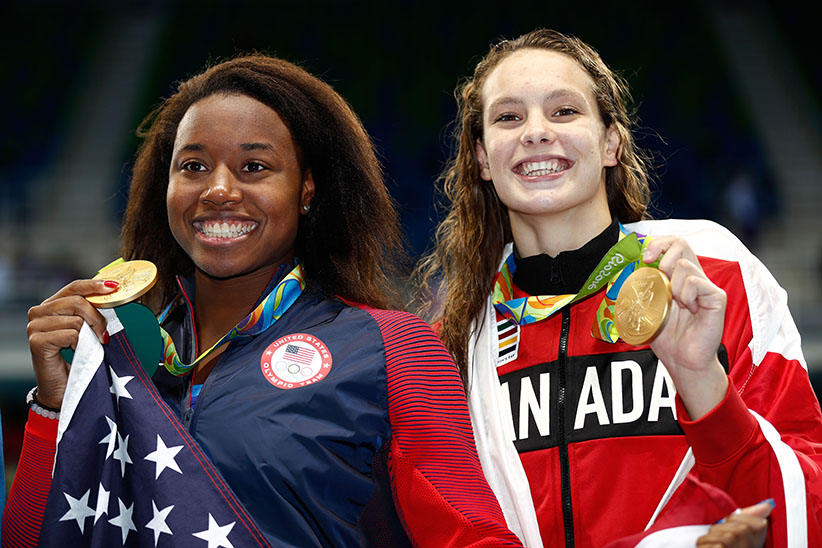

The air is pretty thin up in row “U,” the next-to-last seats at Rio’s Olympic pool, but that’s not why the Oleksiak family was having trouble breathing. At the 50-m turn of the women’s 100-m freestyle race, Penny was in seventh place, almost a full second behind the leader and world record holder, Cate Campbell of Australia. Then she surged in the back-half, piston-kicking, arms slicing the water like scythes, reeling in her competitors one by one until she touched the wall. It took a while to establish what had happened—a tie for gold with Simone Manuel of the United States. Penny’s sister, Hayley, 22, dropped to her knees, screaming, and hugged their mother. Jamie, 23, who had paid to bring the family to Brazil after Oleksiak unexpectedly made the team at the Canadian trial in April, claims he slipped into shock, unaware that his little sister was Olympic champion until the others told him. “It was a thousand emotions at once, it was so overwhelming,” he said, a couple of minutes after she climbed the top step of the podium. “Leave it to Penny to make it a roller coaster, you know what I mean?”

Down in lane 5, Oleksiak stared straight ahead at the wall for more than 20 seconds before finally daring to turn around and take a peek at the scoreboard. “I can’t remember the noise. I just remember seeing flags and people clapping,” she says. “Then I turned around and saw the number and everything hit me at once. I heard everyone screaming. It was kind of like a movie.”

Her family moved down to the good seats for the victory ceremony. As she made her way around the pool, gold dangling around her neck and a Canadian flag in hand, she climbed up to them, embracing and crying with her mom, dad and Hayley, and settling for a stiff and awkward hug with her hulking brother. “We don’t hug a lot and whenever we do it’s like my mother saying, ‘Penny, hug your brother, he’s like, leaving for a year,’ ” she explained. “And I go, ‘OK, bye.’ ”

Richard’s not much of a talker. But Alison, fighting the official Rio Olympic head cold as well as her own emotions, tried to put it all into words. “She’s such a tough nut. Very mentally tough,” she said. “For your children to have a passion about something and be able to do something they love, and then to do something like this—we just feel so blessed. I don’t know what we did. We’re just in shock.”

Oleksiak, the youngest of five kids, comes from a particularly sporty family. Both her mom and her dad were college athletes. Her eldest brother Jake played NCAA hockey, and Hayley is a rower at Northeastern University in Boston. But Penny didn’t really learn to swim until she was nine, splashing around and playing Marco Polo with Hayley and other kids in a neighbour’s pool. That fall, she tried to join three different competitive clubs in Toronto, but failed because she couldn’t complete the requisite two laps of the pool.

Gary Nolden, who finally took her on at the Midland Pool in Scarborough, remembers that she couldn’t breaststroke to save her life. “It was a combination of freestyle with breaststroke pull and a fly kick—it was just a mess.” But there was always plenty of determination. When she was 10, Oleksiak got involved in a contest with a bunch of 14- and 15-year-old boys to see who could do the most push-ups on the edge of the pool deck. She kept going until her arms gave out and she fell face-first into the cement, breaking her front tooth in half. A day later, after a trip to the dentist, she was back in the pool doing her lengths. By the time she was 11, Nolden knew she was special. “Every time she swam she got faster. Every time she showed up at the pool, she was an inch taller,” he says. (Oleksiak, who is currently six foot one, having sprouted three inches in the last year, has been the tallest kid in her class ever since she started school. “I was always in the back row of every class picture,” she says.)

Oleksiak first caught the eye of Canada’s high-performance program that same year. One Wednesday night, she was swimming at the University of Toronto pool with her club, alongside members of the national team, when Ben Titley, the head Olympic coach in Rio, saw something intriguing. “It was her size, her limb length, the way she just moved through the water. I do remember thinking, ‘Whoa, what the hell is going on here?’ ” Titley, an Englishman, had been one of Great Britain’s Olympic coaches in Athens, Beijing and London. It was his first week on the job in Canada. He asked Bob Hayes, a Toronto Swim Club coach, if he could pull Oleksiak out of the water and introduce himself. “I said, ‘Hi I’m Ben,’ and I shook her hand, and I said, ‘Holy s–t! Her hand is the same size as mine!’ ” They talked about her favourite strokes. “I noticed that she has the features of a large person, so I asked, how tall is your dad? And she laughed and pointed to the stands and there’s Richard, this six-foot-nine giant sitting up there,” Titley recalls. “And I said, ‘OK, that’s good. Do you have any brothers or sisters that play sports?’ And she laughs, and says, ‘Yes, my brother’s an NHL defenceman, and he’s like six-foot-seven.’ ”

Titley began working with her, sporadically at first, then once a month, then once a week. As a 14-year-old at the 2014 Canadian Age Group Championships, Oleksiak won 10 individual medals—five gold, three silver and two bronze—setting a personal best in each and every race, and then tacked on three relay golds. At the 2015 FINA World Junior Championships, she won six medals. A year ago, she started training full-time with Titley and the other high-performance athletes at the new Toronto Pan Am Sports Centre. In April at the Olympic trials, the still 15-year-old won gold in 100-m butterfly and 100-m freestyle, as well as a silver in the 200 free, punching her ticket to Rio. The principal at her school, Monarch Park Collegiate, offered her* congratulations over the PA system first thing on the Monday morning.

For all her raw talent, Oleksiak’s sudden dominance on the world’s biggest stage is something of a shock to both her coaches and competitors. “It might sound strange to people back home who say, ‘Oh, she’s Canada’s best swimmer.’ Well, that’s happened in the last three months,” says Titley. “The nine months prior to that, she was the one chasing Chantal [Van Landeghem], chasing a Sandrine [Mainville], chasing an Audrey Lacroix.” The idea was to make the teenager tap into her competitive instincts and push her limits through a daily dose of humility. “Getting beat was normal,” says Titley.

But it wasn’t just Oleksiak who rose to the occasion in Rio. Kylie Masse of Windsor, Ont., won a 100-m backstroke bronze, setting a new Canadian record. Then Hilary Caldwell came third in the 200-m backstroke, giving Canada its first two medals in the discipline since 1992. When the relay bronzes are factored in—whether you swim the preliminary, or the final, everyone on a winning squad gets a bauble—11 of the 19 women on Team Canada are returning home with Olympic medals.

“It’s made me that much more antsy, seeing all these girls swimming so well. I want my part in it,” the 25-year-old Caldwell said the night before she went out and sealed the deal. “We’ve had all these Canadian girls on the podium, so if they can do it, I can do it.”

John Atkinson, high performance director for Swimming Canada, talks about the multiplier effect of all of those swimmers going back to their clubs and inspiring 11-, 12- and 13 year-olds to strive for Tokyo 2020, or the 2024 Summer Games. Since taking over the Canadian program in March 2013, he’s been preaching three things: improvement of times, progression through heats to finals, and finally, conversion to the podium. All were on abundant display in Rio. He points to the example of the women’s 4 x 200-m freestyle relay team. A year ago at the FINA world championships in Russia, they finished 11th, with a time of 7:57. At the Olympic pool, they timed 7:45 and won bronze. “They actually improved by 11.92 seconds in a year,” he says proudly.

The performance of Canada’s men wasn’t quite so inspiring. The much smaller squad—just nine swimmers qualified—failed to reach the podium, although Santo Condorelli came heartbreakingly close, finishing fourth in the 100-m free by 0.03 seconds. Overall, Canada won the fifth-most medals in Rio’s pool. But the women were second, behind only the mighty United States. Atkinson hopes that swimmers like Condorelli, 21, 18-year-old Javier Acevedo and Markus Thormeyer, also 18, can help the men catch up by 2020.

For the moment, Oleksiak is Canada’s undisputed superstar. She came into her first real senior international competition and not only established that she belonged, but that she counts among the very best in the world. “There’s no fear. She just gets in and races,” says Atkinson.

The original plan was to have Oleksiak come to Rio and get used to the bright lights and media attention. The challenge for next year was to become competitive. Winning medals was supposed to start happening in 2018, two years out from the Tokyo Olympics. “What’s happened is, with her extremely long legs, she’s leaped a couple of steps,” Titley says wryly.

Those who are in charge of Canadian swimming know they have something rare and special. Titley has coached a number of world record holders and admits that there are things this 16-year-old does in the pool that he has never seen before. The challenge is that while Oleksiak is now an Olympic champion in the record books, she is still very much a teenager at heart.

Titley, who is 39, spent a lot of a time at these Games listening to Drake and Chance the Rapper as he endeavoured to connect with Penny and his other young swimmers. “I didn’t even know who those people were. I didn’t know any of that music stuff,” he says. “But I had to get down with it, or whatever. I’ll just stand there and bob my head. And they’ll find it funny that I’m into it. I don’t care, but they do.”

He worries that Oleksiak might start reading all the nice things people are writing about her and believe them. That she’ll develop bad habits, or hang out with the wrong people and become one of those flash-in-the-pan medallists who beat the world once, then never find the magic again. “For me that’s not acceptable,” says Titley. “This kid needs to be getting results for Canada over at least the next two, and maybe three Olympic Games.” Alison and Richard, who seem to be the only ones to call their daughter by her full name, Penelope, are worried about just the opposite: that she’ll become too obsessed and professional and miss out on friends, school and life.

On the first night of the Games, following the 4 x 100-m bronze, all five members of the team stepped out to meet the media. Sandrine Mainville, 24, Chantal Van Landeghem, 22, and the two 16-year-old wonder twins, Ruck and Oleksiak, who had swum the final and got to stand together on the podium for the victory ceremony. And Michelle Williams, who didn’t. The 25-year-old from Toronto cried when she was dropped in favour of Penny after the heats, but came out to cheer on her teammates regardless. As the photographers grouped the women together for a picture, Oleksiak quietly took the bronze from around her own neck and draped it over Williams’s shoulders.

The kid is going to be all right.

In the giant tent of a training room, just outside the swim stadium, Team Canada ended up right next to Team USA. Penny Oleksiak, Olympic medallist, was a little too shy to go and introduce herself. “I caught myself looking over and being, ‘Oh my goodness, it’s Nathan Adrian, or Michael Phelps, or Katie Ledecky’,” she says. “Then I’d make eye contact with them and I’d have to walk away. I don’t know why.” Reflecting for a second, she does, actually. “They’re all people I look up to.”

Other swimmers paid attention to her, though. Chad Le Clos, the South African who beat Phelps for gold in the 200-m butterfly in London, and inspired the #Phelpsface memes this time around, introduced himself and they chatted a bit. In fact, the whole world took notice of the Canadian women at this meet. Kierra Smith of Kelowna, B.C., who finished sixth in the 200-m breaststroke finals, shared a story about meeting Missy Franklin, who won four golds for the Americans in 2012 as a precocious 17-year-old. “She sat down with us at dinner the other night and said, ‘You guys are doing so great,’ the 22-year-old Smith told reporters. “I was like, it’s Missy Franklin! I was so excited. She noticed us!”

Oleksiak swears she’s not going to get a swelled head about it all. She’s got her friends back home—the ones she was snapchatting with into the wee hours of the morning after her races, despite promising Titley she wouldn’t touch her phone—to keep her grounded. They call her Pennyroo, like a kangaroo, or Groot. “Have you ever seen Guardians of the Galaxy?” asks Gabe Schnurr, part of her circle at Monarch Park. “Groot is the tree-looking thing. It’s a character made of just roots. She’s pretty awkward.” They tease her about how accident-prone she is: always rolling ankles, breaking a toe by walking into a door in early 2015, and then shattering her elbow when her bike tire got stuck in Toronto streetcar track, just weeks before the world junior championships. “She got really strong with her legs from iso[lation] training after the biking incident, and really strong with her arms from the toe incident,” says Alexis Bragman, a friend from the Toronto Swim Club. Lately, they’ve been sharing all sorts of revealing stories with the media. Like the time her huge appetite and competitive instincts collided in an eating contest with a bunch of male friends at McDonald’s and she devoured seven chicken sandwiches. Or how during a Secret Santa session she once gave another member of the swim club a video of her obliterating his personal best.

On the national team, Oleksiak is the baby, just like at home. (Before the Olympics, her teammates called her “the child,” although the nickname no longer seems appropriate.) Last winter, when she was falling behind at school and Alison was threatening to keep her away from the pool, they rallied around to tutor her. Sandrine Mainville, from Boucherville, Que., helped Penny with her French homework. Rich Funk, a breaststroker from Edmonton, helped her with math and science. She has more than one family.

What makes Oleksiak so dangerous in the pool is her closing speed, that capacity to keep going fast toward the end of a race, when everyone else is getting tired and slowing down. That’s what she’s been practising all these months, going hard for 50 or 150 m, then going even harder from the final turn to the wall. That’s what won the gold. “I just put my head down and go as fast as I can,” she says. It’s an elusive skill, one that is shared by all great swim champions. But that alone isn’t enough to win you four medals at the Olympics. Something else has to sustain you through those endless hours of training, in and out of the pool.

For Oleksiak, it might be as simple as the fact that she hates to be beat. She was that way as a little kid doing bike races with her sister. And still today at the Rio pool, where she emerged scowling and downcast after the 4 x 100 medley relay team set a new Canadian record, but ended up fifth overall, her only non-podium finish of the Games. “It’s just because we had the opportunity to medal and the girls on the team fully deserved a medal and I just kind of feel like I let them down,” she says the next morning, when we sit down to talk. “I think I should have been able to catch up or something.” At 16, she’s already a leader.

Penny Oleksiak loves to swim. “Being underwater is kind of weird. There’s no noise. It’s very quiet. I like just having that silence,” she says. “When you’re racing you can’t hear anyone and you’re just in your head. It’s pretty cool to know that everything is just you and it’s just a mental game.”

Whether she understands it or not, Rio has changed a lot of things. She’s famous, and a champion. No one will underestimate her in the future, they will only want more.

But there will always that be precious alone time in the pool—as Canada watches and cheers, whether she can hear us, or not.

—with Aaron Hutchins

CORRECTION, Aug. 21, 2016: This story originally misstated the gender of Penny Oleksiak’s school principal.