Alberta’s election, and the ugly politics in store for Canada

Jen Gerson: A vacuous, exhausting, divisive campaign where casting your opponents as bigots wasn’t enough to win.

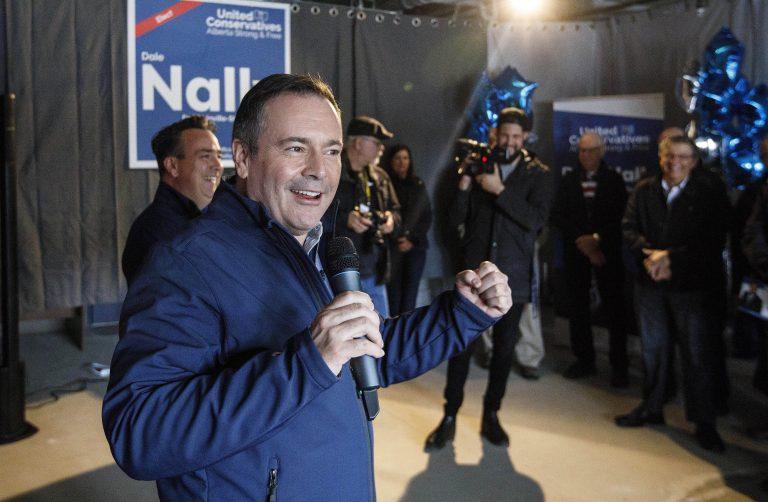

United Conservative Party leader Jason Kenney speaks at a rally before the election, in St. Albert, Alta., on Monday April 15, 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jason Franson

Share

If you look up the Alberta government’s own economic review and indicators, you eventually land on a page filled with headlines like this; Alberta labour market softening, Alberta inflation cools, Trade sector stabilizing following recent weaknesses, shipments fall with lower energy prices, Alberta employment starts 2019 on a weak note.

Some bad news, some middling news, the occasional crack of progress. It goes on and on like this. Page after page. For years.

What those mild headlines hide is the human cost of stagnation; a spike in the suicide rate, an opioid crisis. Working-age men and women taking to road medians to beg throughout this winter’s polar vortex—a particularly nasty season in which -20C seemed to cling to the province for weeks.

These are not the sort of conditions that tend to be friendly to incumbent governments.

The United Conservative Party has polled with double-digit leads since Jason Kenney won its leadership in 2017—and has held strong support ever since. Under Kenney’s leadership, the vote split on the right is now a thing of history.

READ MORE: Can Alberta stay conservative enough for Jason Kenney?

If there was even the smallest chance of overcoming all this, the NDP would have needed to run a perfect campaign. The NDP did not run a perfect campaign. Hoping to replicate the last-minute electoral shift of 2012, in which the Wildrose Party’s near-certain victory seemed scuttled by the now infamous revelation that two of its candidates made homophobic and racist remarks, Rachel Notley’s party relied on a stream of damaging leaks about candidates and nominees from the UCP.

Many of the “bozo eruptions” of 2019 made the Wildrose predecessors seem tame by comparison. While some warranted genuine scrutiny and did reflect poorly on the UCP, others proved thin upon closer inspection. The NDP and its allies seemed unable to discern the difference. As a result, there were so many that the eruptions, paradoxically, became easier to dismiss as wholesale character assassination.

When these stories stopped chipping away at UCP support, the NDP didn’t seem to have another plan.

It simply wasn’t enough for the NDP to paint the UCP as a party of bigots and homophobes; the party needed to speak to the fears of centrist voters craving a credible vision for the economy. Albertans, frustrated by regulatory quagmire coming out of Ottawa, were looking for a genuine passion for the fight for pipeline access, and a defender of the oil and gas sector.

Notley is considered to be far more likeable than Jason Kenney, even among conservative voters. But Albertans weren’t looking for someone likable. This province voted for a leader who will howl and kick and bite. If it’s fair to criticize the NDP for running a particularly personal and divisive campaign, it should also be noted that the UCP message wasn’t one of hope and sunshine, either.

Kenney often nodded darkly to the Notley-Trudeau “alliance.” There is a Manchurian Candidate undertone to this allegation; it suggests that Notley’s comparative lack of pugnaciousness, her willingness to work with Ottawa on climate change, for example, was an indication of her true loyalties. She attended anti-oil sands rallies in the past, after all, and opposed Northern Gateway and Keystone XL; some of her supporters and MLAs actively opposed the dirty “tar sands” before the NDP came to power.

This interpretation requires we skip over a few key points; that Notley had no say in Keystone XL, and opposed it because she said she supported more refining jobs in Alberta at the time. That Northern Gateway was a dead letter by the time she came to office.

It also requires us to ignore the fact that the federal government spent $4.5 billion on the TransMountain pipeline and subsequent expansion, consultations for which are expected to be completed in May. That last note is dismissed by the conspiracy theory—now cant in much of Alberta—that the federal purchase was really a very roundabout way of killing the expansion. Nevermind that the entire project would have been dead if the federal Liberals had done nothing and simply allowed Kinder Morgan to walk away, as the company threatened to do.

This drift toward bellicose conspiracism was present in Kenney’s own acceptance speech on Tuesday night. Knowing the country was listening, he promised to launch lawsuits and inquiries into the host of foreign-funded environmentalists who have worked assiduously to landlock Alberta’s oil.

“To the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Tides Foundation, Lead Now, the David Suzuki Foundation and all of the others: Your days of pushing around Albertans with impunity just ended. We Albertans are patient and fair minded, but we have had enough of your campaign of defamation and double standards.”

This line garnered massive applause. It has the uncommon advantage of uniting the province against a common enemy (or, rather, several common enemies. That growing list includes B.C. and Ottawa, which will soon sue us, or be sued by us, respectively.)

Whether all of this will spark a wave of new investment in the oil and gas sector is up for debate, but Alberta’s legal sector can certainly expect a renaissance. Process servers and lawyers in dire need of billable hours take note: Alberta is open for business. This provincial election has been a dry run for the federal one in October. It was an incumbent progressive defending a surprise win against an ascendent, populist conservatism.

Yet Rachel Notley is a much stronger politician than Justin Trudeau. And Jason Kenney is a more able and talented contender than Andrew Scheer. This was a pairing of two of the strongest politicians in the country. Instead of a clash of titans, what we saw was a campaign so vacuous, exhausting and divisive that even the kindly volunteer running my suburban polling station—the sort of soul who forms the very sinew of a healthy democracy—said he was exasperated by the whole affair and happy for the campaign to be over.

It’s a sign of nothing good to come.

Casting your opponents as bigots isn’t enough to win. And if there are any downsides to running a campaign that appeals to a desire to lash out at the world, well, Alberta is about to find out.