Dear sister: ‘I wonder if my silence played a hand in your suffering’

‘I had been conditioned to believe that racism was no longer real. So my approach to bullying and abuse has been to suck it up,’ writes Téa Mutonji in a letter to her sister. ‘Now, I wonder if I should have spoken out so that, seven years later, you didn’t experience it too.’

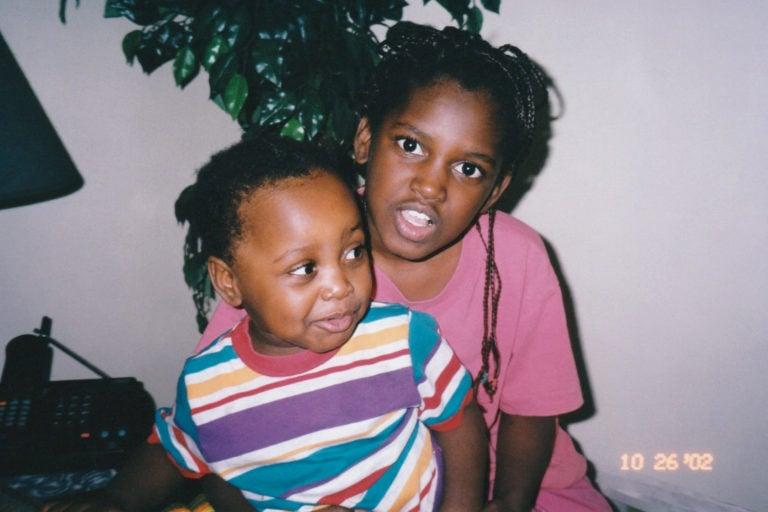

Téa Mutonji with her sister, Ornella (Nella) Mutonji

Share

Do you remember that night when you were in Grade 11 and you complained about the racism at our high school? I was living in a rooming house in Scarborough, Ont., 40 minutes away from our home in Oshawa. I didn’t know what to do so I bought The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, a novel about a Black girl in a predominantly white school.

Another time, you mentioned that you were experiencing symptoms of anxiety, depression and paranoia. “It’s because of the way people look at me,” you said. So, I left Depression & Other Magic Tricks by Sabrina Benaim on your bed. What you described were experiences I shared, but I hadn’t yet begun to unpack them. I didn’t know how to help you.

We’ve had a different set of circumstances—my friends are mostly white and your friends are mostly Black. But racism doesn’t have limits. I thought that since you had friends you could relate to, in terms of race, culture and religion, it would exempt you from the kind of pain I experienced—the effects of racism lingered in my psyche, my sense of self, my desires.

[contextly_sidebar id=”eq3RkkcMcb5wf19hjJaHw2jkEk8hfl0o”]

I had been conditioned to believe that racism was no longer real. So my approach to bullying and abuse has been to suck it up. For years, being silent was my form of survival. Now, I wonder if my silence played a hand in your suffering; if I should have spoken out so that, seven years later, you didn’t experience it too. When you and your friends hang out in your room, I hear the way you support each other and use humour to get through your struggles . . . that gives me hope.

Talking with you and watching you reminds me that we, Black people—Black women—aren’t the problem. White supremacy just makes this difficult to believe. It hinders the growth and wellness of our children everywhere. I admire the way you treat your Blackness with compassion, despite feeling targeted. You’re resilient. You don’t back down. You can’t be pushed around. I’m older than you, yet you were the one who taught me that being silent can make me complicit.

Do you know what happens to us when we’ve been programmed to accept the way the world looks at us? Exhaustion. We are taught to suppress our feelings and play the role of the “strong Black girl.” And when we talk about our deteriorating mental health, we are seen as weak; or worse, as people who are piggybacking on ancestral trauma.

READ: Hal Johnson: ‘Yes, there is systemic racism in Canada’

At what point does exhaustion turn into something else—depression, phobia, uncontrollable fear? And how often is that properly diagnosed? I know you don’t have the answers to these questions. I only ask in the hope that these questions will guide you toward aggressive self-care. I don’t mean bubble baths and scented candles; I mean tenderness, rest and community.

Oppression, microaggression, systemic racism and gaslighting can lead to depression, racial PTSD and shame. This is something I’ve only recently learned about. Through this, I’ve had to consider the failure within Black communities in acknowledging our collective mental health crisis. This also means recognizing the role I played in invalidating your struggles. If I ever made you feel like you weren’t deserving of my care, I’m sorry, Nella. The books, the poetry, the movie nights were not enough.

Since I moved back home this spring, I’ve seen that you’ve turned into your own woman—passionate, talented, outspoken. You see that the world is full of potential. You imagine a place where little Black girls have equal opportunities. Through your art, your storytelling and your love for history, you proclaim yourself as worthy. But I want you to know that moving in order to find a more forgiving city isn’t the answer. We, Black women—Black people—don’t need forgiveness. We have nothing to be forgiven for. What we need is each other.

What you’ve experienced here in Oshawa, you might also experience in a more diverse city. The pain you feel, the resentment, the fatigue, those are real and valid responses to the world we live in. It has nothing to do with your Blackness, which is beautiful, bold and magical. So, take your mental health seriously. Be your own advocate. Give yourself permission to get angry and to break down. And if you find yourself in a tiny apartment in downtown Toronto, afraid of the world around, call me. I promise that this time, I’ll know what to do.

This article appears in print in the August 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Dear sister…” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

The piece is part of Maclean’s Before You Go series, which collects unique, heartfelt letters from Canadians taking the time to say “Thanks, I love you” to special people in their lives—because we shouldn’t have to wait until it’s too late to tell our loved ones how we really feel. Read more essays here. If you would like to see your own letters or reflections published, send us an email here. For more details about submitting your own, click here.