How Doug Ford could help us get electoral reform

Stephen Maher: A majority PC government in Ontario, led by an unqualified Ford, could be a powerful example of the need to change our electoral system

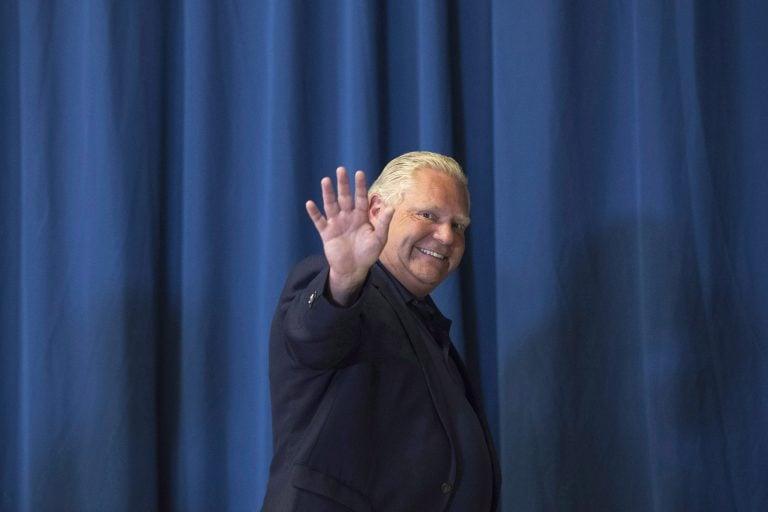

Progressive Conservative party leader Doug Ford waves to the media during a campaign stop in Kingston, Ont., on Sunday on June 3, 2018. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Lars Hagberg)

Share

[widgets_on_pages id=”ontario_2018_election_live”]

As this goat rodeo of an election comes to its chaotic and dismaying conclusion, it looks like 39 per cent of Ontario voters are about to hand the Progressive Conservatives a majority in spite of that party’s sustained and surprisingly creative effort to demonstrate that it should not be trusted to run a tractor pull, let alone an $830-billion economy.

The disorderly pageant of ineptitude reached another low point on Tuesday morning when Doug Ford stood in front of reporters and failed to respond substantively to unproven but detailed and disturbing allegations in a lawsuit filed by Renata Ford, widow of Rob. Renata says Doug is mismanaging the label company his father built, running it into the ground, and denying Rob’s kids their inheritance or a proper accounting.

Ford could have refuted the claim that the company lost $2 million in 2016 and $1.5 million in 2017, for instance, but did not. He called the allegations in the lawsuit “false and without merit.”

In the same news conference he promised “massive investments” in health care, a 10-cent-a-litre gas tax cut, plus a 20-per-cent middle class income tax cut, a combination that would inevitably drive the province deeper into debt than it already is after many years of costly Liberal scandals.

The Progressive Conservatives, who ought to stand for fiscal discipline, have not released a costed platform, although Ford had said they would, which may mean he was not able to do so because that’s not the kind of thing he is capable of doing.

READ MORE: Ontario election 2018 platform guide: Where the parties stand on everything

His lack of qualification for the job at hand is unusual at this level of politics, and I am mystified why PCs didn’t give the job to Christine Elliott, who could have cruised to an easy majority win.

There is nothing in Ford’s political career—one four-year term on Toronto city council—to show that he has the discipline or skill to put together a costed platform, let alone run Ontario, and it is hard to know what to think of his track record as a businessman.

If the polls are wrong, or Ontarians take a last look at Ford and decide to hedge their bets, the other party that might win—Andrea Horwath’s NDP—looks similarly ill-equipped to ensure the future prosperity of the province.

While Horwath is more of a known quantity than Ford, she has always behaved like a doctrinaire representative of the labour movement, and during the campaign she repeatedly missed opportunities to show that she is concerned with the challenges Ontario businesses face, or signal that she might ever say no to public sector unions she would face across the negotiating table.

And unlike Ford, who has an impressive team, Horwath has no high-profile, experienced candidates, and many with the kind of fervent left wing views that only thrive on college campuses.

That leaves the Liberals, whose leader is so unpopular that she was forced, partway through the campaign, to pre-emptively declare defeat, apparently in the hopes that it would allow some of her strongest candidates to campaign without reference to her.

There will be a lot of nose-holding when Ontario voters go to the polls on Thursday.

In the circumstances, the best we can hope for is a minority, led by Ford or Horwath, for a year or so, to allow someone to run the province on a short leash while the parties all compete to come up with better packages in the next election.

Instead, we are likely going to get a Ford government, even though most voters dislike and fear him.

Our first-past-the-post electoral system routinely gives majority mandates to governments elected with 40 per cent of the vote, massively distorting the will of the voters.

The worst example in our history was the 1993 federal election, when Jean Chretien got a majority with 41 per cent of the vote, the Bloc Quebecois got 54 seats with 14 per cent of the vote and the Progressive Conservatives got two seats with 16 per cent of the vote. That distortion greatly strengthened the Bloc and weakened the Tories, who were punished for having wide but shallow support.

The only reason why we have not changed our system is that the people who have the power to make the change—governments—get more power than they deserve under the current arrangement.

We have an excellent recent example of that in Ottawa. Justin Trudeau promised that the last election would be the last one carried out under the first-past-the-post system and then cravenly reversed himself, spouting nonsense.

This is part of a long history of Canadian governments finding ways not to deliver electoral reform.

In British Columbia this fall, that might change, when the NDP-Green coalition government runs a referendum that, if it passes, would bring proportional representation to that province.

Or Quebec may be the first. All the opposition parties there have agreed that the next government will change the system, and the Liberals face a challenging election in October.

If Ford is running Ontario while these debates are taking place, and if he is the kind of premier I am afraid he will be, he will serve as a powerful symbol for the need to change the system.

CORRECTION, June 6, 2018: This column has been changed to correct an error concerning the distribution of seats in the 1993 and 1997 federal elections.