Is To Kill A Mockingbird still relevant to Ontario students?

Carl E. James: In our country’s racially diverse generation of students, we should consider whether ‘classics’ that repeatedly use the ‘N’ word are reasonable in our classrooms

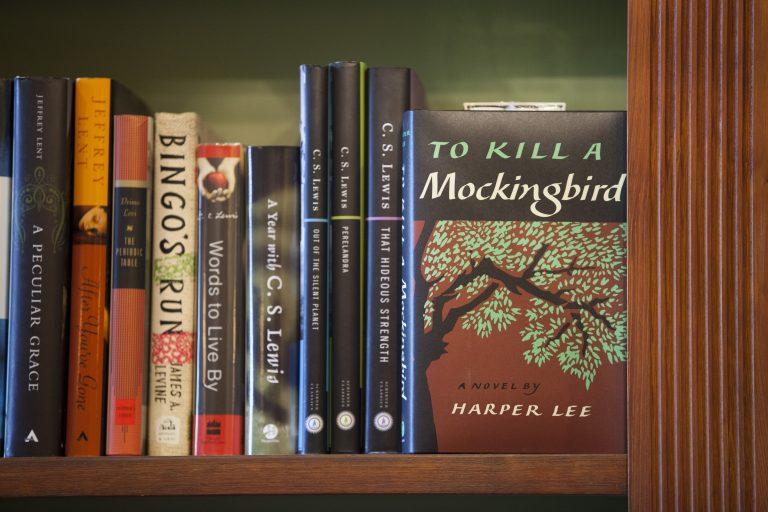

A new printing of the book ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ by author Harper Lee, is on display at Faulkner House Books, on May 28, 2015 in New Orleans, Louisiana.(Melanie Stetson Freeman/The Christian Science Monitor/Getty Images)

Share

Carl E. James is a York University professor. In 2016, he was appointed York University’s Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community and Diaspora. In his role, he seeks to address the issues and concerns of marginalized people through community engagement.

First published in 1960, Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, has been widely used over the years in Canadian classrooms and elsewhere in the world. The book is considered a “classic” among the English literary canon, but like every other teaching material, I believe it should be continuously assessed in relation to historical and contemporary contexts, and to the cultural backgrounds of the students engaging with it.

In today’s more culturally and racially diverse generation of students, we must examine the extent to which the educational materials like To Kill A Mockingbird, that might have been tolerable or reasonable years earlier, remains so now, given the word “nigger” is littered throughout the text.

Set in the southern United States where Jim Crow laws operated to maintain anti-Black racism, the ‘N’ word was commonly used to refer to African Americans then.

The book’s narration of the white liberal logic centres on Atticus Finch, a white liberal protagonist lawyer whose progressive values compels him—against great personal odds—to save Tom Robinson, a Black man, who has been falsely accused of raping a white woman in the fictional Alabama town of Maycomb. Scout Finch, Atticus’s daughter, narrates the book by providing commentary on the impact of the trial.

For a story that focuses on racial injustice, it’s telling that we hardly hear the Black character’s thoughts on the matter.

MORE: Why race and immigration are a gathering storm in Canadian politics

In more than 20 years as a researcher and professor at York University, where my scholarly interests include bolstering educational and occupational access to marginalized youth, I’m particularly interested in the schooling experiences of Black and racialized students at all levels of the education system. What I have found—and over the decades it remains true—is that the poor academic performance and educational outcomes of Black students in Canada can be attributed to the historic and systemic nature of anti-Black racism embedded in Canadian society, which inform our educational institutions.

While some changes in inclusivity have taken place in our contemporary school systems, Black youth still experience a teaching-learning process that’s not responsive to their needs, concerns and ambitions. The current system has serious shortcomings: it leaves a gaping hole in Black Canadians’ history and in history text books, which should start with the history of Indigenous peoples and tell of slavery in Canada; it disciplines Black students more harshly than their peers; it streams them into courses below their ability and skill levels; and discourages them for attending postsecondary institutions (especially university).

Significant also is the fact that Black students from the elementary to the post-secondary level, must contend with the cruelty of low expectations and the normalization of poor outcomes. If we’re to create educational systems that support the personal and academic development of all students, and encourage a sense of belonging amongst all learners, then we should recognize that educational choices—including that of teaching materials—are not neutral.

MORE: Every child left behind: How education cuts fuel inequality

Research I conducted in spring 2018 with 44 Black students attending schools in Ontario’s Peel District School Board revealed that one of students’ main concerns at school was the use of the ‘N’ word, which one student told us, “people are getting too comfortable with saying.” The students said that the ‘N’ word stereotypes them as “bad news,” that it presents them as the kind of people to “stay away from,” and as such they’re hurt, offended and angered by its use.

In her New York Times book review of author Tom Santopietro’s book Why ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ Matters, African-American essayist Roxane Gay said that the Black people in To Kill A Mockingbird are “narrative devices, not fully realized human beings.”

“Robinson and the family’s housekeeper, Calpurnia,” Gay goes on to write, “are mostly there as figures onto which the white people around them can project various thoughts and feelings.”

So even in the story of their own oppression, the book’s Black characters remain on the margins. The novel ends with Tom Robinson’s murder as he tried to escape prison, but it’s Atticus Finch that readers celebrate and remember with empathy and admiration. This implies to students that Black people’s attempts to address the anti-Black racism they suffer can only be done with the help of a white liberal, who represents the white power structure.

For Black students who experience racism in their educational lives, the novel might not only be a reminder of those experiences but a suppression of their humanity and silencing of their voices.

In the late 1990s, after African Nova Scotians protested the use of To Kill A Mockingbird, it was removed from the authorized learning resources list for use in Nova Scotia public schools. In 1996, the book was replaced by Ernest J. Gaines’s novel, A Lesson Before Dying, which was determined to be a more suitable learning resource that educators can use to address the topics and themes found in Harper Lee’s novel. I would recommend Black Boy by Richard Wright, a memoir and personal account of the racism Wright faced as a poor Black boy in America.

Asking teachers to critically consider the use of educational materials that likely have a negative effect on students is certainly not de facto banning a book, but scrutinizing all learning materials for their current cultural relevance.