‘Self-sufficient and unassuming’: What it means to be Gen X

Sharon Bala: “Half a century on, Gen X remains undefined, evading categorization, unwilling even to raise our hands during roll call. Children of the Silent Generation, perhaps it’s fitting that ours is invisible.”

Sharon Bala in her St John’s home (Photograph by Heather Nolan)

Share

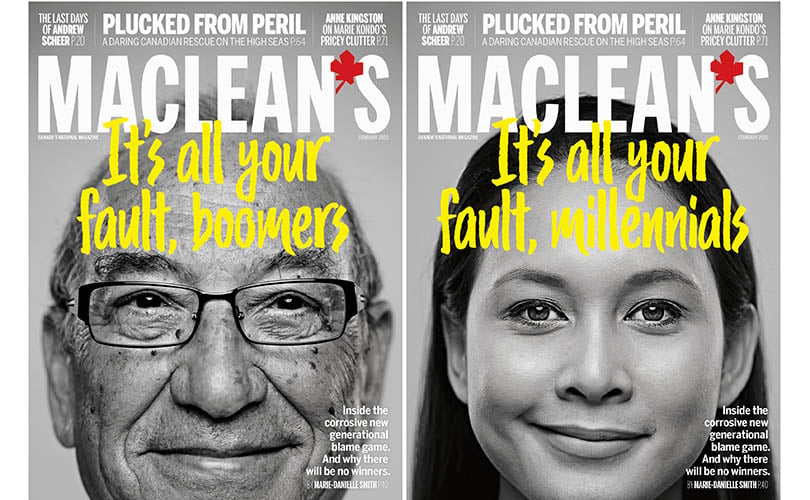

This essay is from the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine, which charts the current conflict between boomers and millennials—one of the defining struggles of our age. The issue has two different covers. Here’s why.

When the editors planned this two-cover magazine, they must have forgotten Gen X. Sandwiched between the bombastic boomers and shouty millennials, we’re the overlooked middle child, a small cohort no one bothered to properly name. While the siblings duke it out, and Gen Z bounces on the ropes chanting “OK boomer,” we lay low with the popcorn.

But recently, Z has grown wise to our game. They’ve started calling us “Karen.” (Which, can I just say? I expected more gender neutrality from you, Z.) Karen, if you aren’t up on your memes, is a blonde mom with a Volvo and acrylics, “currently at your workplace speaking to your manager.” So when Maclean’s came calling, other writers demurred, refusing to cop to it. “What’s Gen X,” those slackers hedged with a shrug. “I dunno.”

The conventional narrative of our generation goes like this: we’re the original latchkey kids. Two parents in the workplace and soaring divorce rates saw us shuttling between households, left to raise ourselves in a halcyon sugar high of Pop-Tarts and benign neglect. The result was a self-sufficient and unassuming generation. We go about our business quietly, refusing to take credit, refusing even to write a half-cocked apologia in a national magazine. This notion of Gen X is a neat and tidy box, but not all of us find it cozy.

COVER STORY: Inside the corrosive new generational blame game

Gen X is diverse, the first cohort with a strong contingent of colour thanks to Canadian immigration policy changes in the ’60s and ’70s that opened the door to newcomers from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. And for those of us who were raised by immigrant parents, latchkeys and Pop-Tarts, the rebellious, devil-may-care teens of a John Hughes movie bore exactly zero resemblance to our lives.

While their counterparts were dropping coins in a jukebox or acid on their tongues, immigrant parents were plotting escapes from politically and economically unstable countries. Naturally, they never let us out of sight, clutched their hair, and just as often a slipper, while meting out discipline over some slight infraction. Those of us with live-in grandparents waiting to pounce the second we walked in the door suffered under the added tyranny of a multi-generational regime. Oh to be a dazed and confused slacker! Try bringing a 95 per cent score on a math test home to an immigrant parent. Where’s the other five per cent? Where’s my slipper?

If Gen X shares certain traits, an innovative streak, say, or the propensity to duck and cover, then the crucible that forged us was out in the world, not in our homes.

When I was eight, my teacher conducted a thought experiment. “Let’s say the Soviets decide to nuke the Americans,” he said, pointing at a map and arcing the imaginary missile over Baffin Island. “If their calculations are slightly off, where do you think that warhead will land?” Forty kids flinched in unison, eyes swiveling to the ceiling.

The Cold War fizzled out with the ’80s. (Though, like shoulder pads, it’s made an unwelcome return.) Apartheid followed. Germany got back together but everyone else called it quits. The USSR. Eastern Europe. Yugoslavia. All the geography we memorized in school became redundant overnight.

The Gulf War began and with it the 24-hour news cycle. Later, we watched as O.J. Simpson pulled a runner in his white Ford Bronco. The police chase and the trial were broadcast into our living rooms in real time, the world’s first reality TV. Draw a straight line from the ill-fitting glove to the Kardashian empire.

ANNE KINGSTON: Why intergenerational warfare is a mug’s game

Work hard, stay in school, and the future will be yours, the grown-ups promised. But our entry into adulthood was rocky, stymied by two recessions—one in 1981 and then another in the summer of 1990—when unemployment hit double digits. McJobbed, we rebounded back to our parents’ basements, forced into a protracted adolescence, lives on hold while our elders denounced us as disaffected and lazy. (Thank goodness millennials turned up with their avocados to deflect the heat.) When the corporate ladder turned into a step stool, our progress blocked by boomers who refused to retire, many of us leapt off, opting to work for ourselves.

Still, we got off easy. Between cyberbullying and the climate catastrophe, is it any wonder millennials are ready to cancel everything and Gen Z is saddling up to save the world? Zed. The terminal generation. Which Gen X nihilist gifted them that name?

In our salad days, Gen X were activists too. We planted trees and advocated for the environment, equality and gay rights, forced institutions and culture to make space for women, queer people, and those of colour. And yet now that we’re the adults in charge, many of us with children and skin in the long game, we are doing little to dial back climate change. Some of us are scornful of action or are outright deniers (Karen). Having flown under the radar so long, it’s as if we expect to slip out unnoticed right before the end.

MORE ESSAYS:

‘We had good intentions but we fell short’: What it means to be a baby boomer

‘Directionless and lost’: What it means to be a millennial

‘Don’t you see yourself in us?’: What it means to be Gen Z

The question remains: what is this generation? Half a century on, Gen X remains undefined, evading categorization, unwilling even to raise our hands during roll call. Children of the Silent Generation, perhaps it’s fitting that ours is invisible.

Now, here’s where I come clean. I’m not really Gen X. According to several highly scientific internet quizzes, I belong to the Xennial micro-generation, a subset born on the cusp of the ’80s, caught in the stranglehold between cohorts. We are said to be entrepreneurial and tech savvy, a natural outcome of our analog childhoods and digital adulthoods. Dwelling in the sweet spot between Gen X cynicism and millennial optimism, we represent the best of both worlds. Some of us can even afford to buy houses and eat our avocado toast in them too, if only in an economically depressed east-coast city.

Anyway, I’m beginning to think this whole essay is balderdash. No one agrees when Gen X begins or ends: institutions from the Pew Center to Statistics Canada say 1960 to 1980. Regardless, the notion that millions of individuals can be reduced to a few traits is absurd. In the next issue: twelve writers interrogate their star signs! (I’m Aries in case anyone’s looking for another 1,000 words.)

How often are you carded? Does your community have access to clean drinking water?

Education, wealth, geography, skin colour—those are the factors that shape outlook and personality. As far as I can tell, the only people who put stock in this generational claptrap are headhunters and marketing managers. No surprise Gen X refuses to play along.

This essay appears in print in the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Meet the slackers.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.