It takes a village: How Canada got its first native-born pandas

It takes a village: How Canada got its first native-born pandas

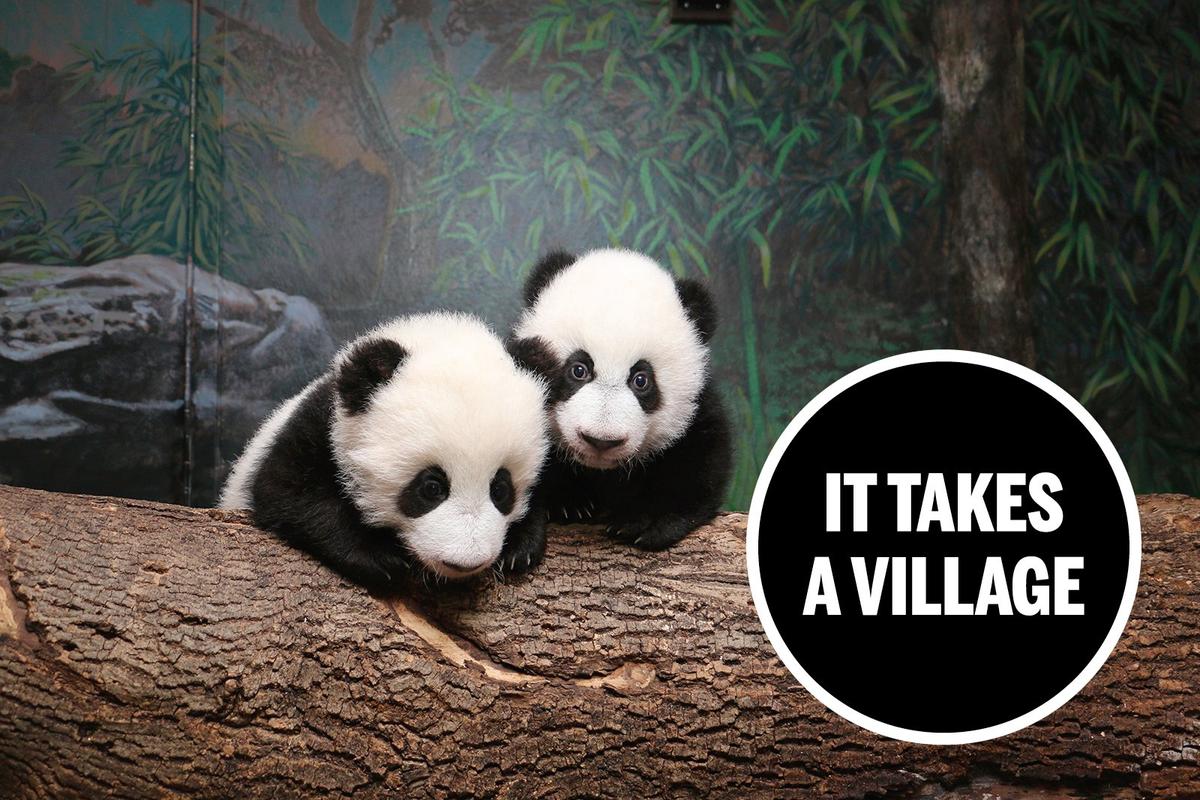

Inside the Toronto Zoo’s heroic, expensive—often downright bizarre—effort to raise twin panda babies

By Meagan Campbell

At the naming ceremony for baby pandas Jia Panpan and Jia Yueyue in Toronto this week, actual trumpets sounded. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau snuck in a visit to the zoo’s panda house just before his White House appearance; Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne skipped question period for the event, and Toronto Mayor John Tory said in a speech that all of Toronto is watching the cubs take their “wobbly steps.”

They are Very Important Pandas.

“Canadian Hope” and “Canadian Joy,” as their names translate from Mandarin, fortify diplomatic ties between Canada and China, our second-largest trading partner. They are also table stakes for the Toronto Zoo,* a multi-million-dollar bet that the twins will drive a surge in admissions, reigniting the pandamania that began when two adult pandas, Er Shun and Da Mao, arrived in 2013. The public frenzy hardly seems extreme, compared to the behind-the-scenes efforts to create and nurture them—a heroic, expensive and often bizarre journey through panda husbandry, government regulation and zoo economics.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau meets Canadian Hope and Canadian Joy prior to the panda-naming ceremony at the Toronto Zoo. March 7, 2016. (Adam Scotti/PMO)

Pandas are formidably difficult to breed.For starters, females ovulate once a year, with a fertility window between 24 and 72 hours. The sperm eventually had to come from China in accordance with Canadian food inspection and airline standards. Staff then had to work 24-7 to swap the twins in and out of the mother’s arms because she would naturally kill or abandon the smaller one.

When the cubs were born in October—making them the first giant pandas born in Canada and two of nearly 1,900* left on Earth—the support team included an artificial insemination expert, animal behaviourist, veterinarian, curator, translator and roster of other panda team members. Behind these cubs are two federal governments, three airlines, seven* full-time keepers and the fifth-largest zoo in the world. “Everything with pandas is intensive,” says the zoo’s reproductive specialist, Gaby Mastromonaco. “The whole package is tricky from beginning to end—but not impossible.”

The World Wildlife Fund reasons that humans should do everything possible to save pandas because we are the ones who have driven them to near extinction by deforesting much of their habitat—and “because we can.” As the icon of the WWF, pandas are the poster children of conservation efforts. “If you don’t have the animal that catches attention, you won’t have the others at all,” says panda keeper Brent Huffman. Mastromonaco agrees. “In the end, if we can’t save pandas,” she says, “there’s no hope for anything else.”

Mao Zedong, founding chairman of the People’s Republic of China, began gifting pandas to the Soviet Union, North Korea and France to build strategic friendships in the 1960s. Later, China began charging for 10-year loans to support conservation efforts and demonstrate China’s economic power. “When you hear things like ‘panda diplomacy,’ ” says Canadian ambassador to China Guy Saint-Jacques, “it’s true that China uses the panda loan for diplomatic purposes.”

Researchers at Oxford University have recently identified a third wave of panda diplomacy, in which loans coincide with trade deals involving technology and natural resources. The Chinese term guanxi describes panda loans as deals based on networking, influence and trust.

So when two adult pandas first arrived in Toronto on a retrofitted FedEx plane dubbed “the Panda Express,” it’s no surprise they were greeted by then-prime minister Stephen Harper and his wife. And that there was a red carpet on the tarmac.

Er Shun, the female panda and Da Mao, the male, were chosen for their sexual compatibility, and the plan was for them to breed naturally. As pandas normally live alone, zookeepers waited until Er Shun’s hormone levels were prime for mating and introduced her to Da Mao at a gate called “the howdy door.” On her peak fertility day, Er Shun waved her bum, seducing Da Mao into her pen, but then decided against the plan. “Er Shun was like, ‘You’re a little panda. You’re not doing it for me,’ ” explains Maria Franke, the zoo’s curator of mammals. On their second date a year later, Er Shun showed interest, but then charged and barked at him.*

As the Toronto Zoo only has the pandas on loan from China for five years, staff decided to artificially inseminate Er Shun before time ran out. Mastromonaco electro-ejaculated Da Mao, inserting an electrical probe in his rectum to stimulate his prostate glands, but the zoo wanted to increase the chance of pregnancy by also collecting sperm from other males. So Franke emailed the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding in China to ask if they would send sperm, which it had never done for another country. Normally, the base requires foreign countries to fly females to Chengdu to be inseminated on site, but it finally agreed that sending sperm could be more efficient. “It was ridiculously amazing that they said yes,” says Franke.

Yet panda semen doesn’t travel well. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency denied a permit for the Chengdu semen because although a certified vet had overseen the process, the vet hadn’t watched the semen be sealed in a canister. So before even trying to fly the sperm overseas, Toronto had to ask Chengdu to electro-ejaculate two pandas again, at the height of Chengdu’s own breeding season. “That’s a lot to ask for,” says Franke.

The first giant panda cubs born in Canada, during tinier times at the Toronto Zoo. Oct. 22, 2015. (Toronto Zoo)

Next obstacle: the airport. To prevent the sperm from spoiling, an artificial insemination expert packaged it with hen’s egg yolk and sealed it in negative 180-degree nitrogen vapour, then attempted to carry it on the plane. Although the zoo had pre-approval from Air Canada and Air China, the bullet-shaped tank of nitrogen vapour, panda sperm and egg yolk didn’t clear security. “There were some phone calls,” says Mastromonaco.

The Canadian ambassador to China stepped in. Part of his job evaluation as a diplomat, Guy Saint-Jacques said, was helping the panda process.“That was part of my performance agreement. This coming at the end of the appraisal period, I wanted to make sure it was a big success.” A diplomatic officer helped smooth the waters when it emerged that a vocabulary issue could scuttle the trip— there is no word in Mandarin for “dry vapour,” and Beijing airport security had assumed the vapour was liquid.

Back in Toronto, Er Shun’s hormone levels were spiking, which meant she was quickly approaching her fertility window. Gabriel Magnus, an animal behaviourist, noticed changes. “She [was] a totally different animal,” he describes. “It [was], ‘I don’t care about bamboo. I don’t care about anything you want to feed me. I want to reproduce.’ ”

When the insemination expert finally arrived in the middle of a May night, Franke met him at the airport in a zoo van, then transferred the sperm into a tank with an alarm to detect any change in temperature that could spoil the sample. According to Franke, “It was more difficult to get the sperm here than the actual pandas.”

Sperm at the ready, the zookeepers kept a close watch on Er Shun’s hormone levels. May 14, just two days after the sperm arrived, was game day. By the time they ran the latest urine samples, it was 5 p.m. To hit Er Shun’s peak fertility time, they only had 24 hours.

The panda cubs get their daily measurements. Oct. 31, 2015. (Toronto Zoo)

Er Shun is called a “giant” panda for a reason. She weighs 219 lb., with molars larger than those of any carnivore and jaws designed to split bamboo, so before Mastromonaco stuck anything into the bear’s uterus, a team of vets and vet technicians * hit her with a dart to put her to sleep. “They’re cute, but they’re bears,” she says. “They wouldn’t appreciate where the straw went. Neither would you.”

The keepers didn’t have time to transport Er Shun to an operating room, so they wheeled a table into the kitchen of the panda house. “I was kind of pumped,” says Mastromonaco. “You don’t realize it’s two o’clock in the morning.” She and three helpers pulled Er Shun onto the table: “We’re resourceful here. Anything up to a rhino we can manage.”

Having warmed up the sperm (which had been so cold in that nitrogen vapour it was considered to have been in suspended animation) and sucked it into a syringe, Mastromonaco injected the fluid into Er Shun—first the sperm from Da Mao, and, later in the morning, from the males in Chengdu. Timing was crucial. “I felt that if I lost that moment, it was all on me,” she explains.

Pandas don’t show pregnancy signs until the end of a three- to six-month “diapause.” The wait began.

To perform abdominal ultrasounds, one keeper popped apples into Er Shun’s mouth, while a veterinarian searched with an ultrasound wand for a foetus the size of a Smartie in the mother’s giant, waterbed gut. Er Shun co-operated, even sticking out her arm to give blood as long as the apples kept coming. She went about her days as usual, maintaining the ideal sleep-eat balance. As all the stakeholders held their breath, Er Shun kept her pregnancy to herself. Pandas, says Franke, “keep you hanging on.”

One of the giant panda cubs is pictured with mom at the Toronto Zoo. (Toronto Zoo)

During a routine ultrasound one September morning, a vet detected a thumping noise, then a second one. Mastromonaco exclaimed: “Is that true?!” A second simultaneous ultrasound confirmed the news. “When we saw that, we had to pinch each other,” says Mastromonaco. “The twins were a bonus. A singleton would have been good, too.”

Although artificial insemination gives pandas an approximate 50 per cent chance of having twins, only one other set has been born and currently live in North America, born at the Atlanta Zoo in 2013. In Toronto’s case, the “twins” could have different fathers. The research base in Chengdu requires that lineage remain unchecked until the cubs return to China in 2023 (the plan is for them to move from Toronto to the Calgary Zoo in 2018.)

Despite the elation, the day they learned Er Shun was pregnant was the start of ongoing stress for the zoo. Panda babies are extremely vulnerable; the female panda at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington was pregnant twice with twins, but the first time one baby was stillborn, and the second time the smaller twin died within a week due to an underdeveloped lung. Further, mothers can purposefully crush their cubs or abandon them after the birth, especially when they have more than one at a time, so leading up to Er Shun’s due date in October, keepers accustomed Er Shun to motherhood by touching her nipples and introducing ultrasounds.

The six-week-old cubs resting at the Toronto Zoo. (Toronto Zoo)

By Thanksgiving, says Mastromonaco, “we were all on panda watch.” On Oct. 13,* after just 45 days of pregnancy, Er Shun was ready to give birth—in the middle of the night. John Tracogna, the CEO of the Toronto Zoo, was at home in bed. “I was sort of sleeping with one eye open,” he says.

At 3:30 am, and again at 3:45 am, Er Shun gave birth to babies that measured one-900th the size of their mother. “If you blink you miss it,” says Mastromonaco, describing the speed of delivery. The cubs were blind, about the size of a stick of butter and shaped like “pink wiggly things,” Magnus describes. As is normal for panda cubs, they were born so undeveloped that the zoo staff couldn’t tell their genders. (The zoo now knows that Jia Panpan is male, Jia Yueyue is a girl.)

When Tracogna’s phone rang, he says, “my heart began to race, knowing this could be the call.”

“I cried tears of joy,” says Bei Wang, the diplomatic officer who negotiated the sperm’s air travel, “because when you become a mom, it’s very emotional.”

Although Er Shun was born a twin herself, she would naturally choose to raise only the largest cub and leave the smaller to die (in this case, Jia Yueyue). For the first months, panda keepers had to approach from the back, hold a bowl of honey to her face, feel around for a cub and pull it from her arms. Then they would substitute the second cub—for the first four months, Er Shun only ever took care of one cub at a time. The process, called “twin swapping,” didn’t exactly trick Er Shun into believing she only had one cub but rather ensured each got equal milk. Sometimes, the mother bear got protective and charged the keepers. “There were a few swaps,” says Huffman, “where Er Shun would leave the baby, looking like she wanted bamboo, but if she saw someone reaching in to take the baby, she’d rush over and put an end to that.”

Once the keepers removed the twin from her arms, they would place it immediately in a Tupperware bin with a blanket and move it to an old incubator donated by the Hospital for Sick Children. “As soon as it came out, it got burrito-ed up,” explains Huffman.

A panda cub weighs in at the Toronto Zoo—a daily ritual. Jan. 10, 2016. (Toronto Zoo)

Shortly after, the keepers handed Er Shun the other cub. Four keepers, including two from Chengdu, repeat the process continually, each working eight-hour shifts. Since the cubs couldn’t thermo-regulate, they needed to be constantly held by Er Shun when they were with her. For the first four months of life, every time a cub left the mother’s arms and didn’t begin to cry, a watchful keeper had to imitate the cry (a baby panda sounds like a bleating goat) to prompt her to pick them back up. In some zoos, where the panda is completely raised by humans, the keepers dress up in panda costumes—so the cubs “grow up knowing they’re pandas and don’t think they’re people,” Huffman says. Now that the cubs are nearly six months old, they can sleep with Er Shun, sometimes both at once—they’re too big to crush, and furry enough to thermo-regulate. The keepers continue supplementing Er Shun’s breast milk with warm baby bottles, a mixture of human baby formula (Enfamil A+) and puppy formula, a recipe borrowed from Chengdu. “It’s not a bamboo smoothie,” Mastromonaco quips.

Instead of changing diapers, Huffman has the unenviable job of stimulating the cubs to pee and defecate by rubbing around their genitals—a task usually performed by the mother when she is with them. One at a time, Huffman holds the cub on his lap, with a garbage can between his legs. “When you get their right place,” he says, “their eyes just close, and they let it all out.” At nearly six months old, they are slowly learning to relieve themselves independently.

Pandas have weak immune systems, so with a squeegee, hose and squirt bottle, Huffman sterilizes the nursery—the plywood playpen, foam kiddie mats and rubber chew toys—along with the entire quarantined panda house. Huffman wears a surgical mask and gown, boils the bottles to sanitize them before nursing, and disinfects his boots in a footbath. The blankets in the playpen are steam cleaned.

A growing panda cub undergoes a health check with a vet. Feb. 9, 2016. (Toronto Zoo)

As the cubs grow, the keepers run exercise sessions with them. “We’re not encouraging them to climb on us or chew on us,” says Huffman, “because they’re bears and the bigger they get, the worse those habits are.” However, “It’s hard not to encourage it because it is so adorable.”

Most of the zoo staff members have never worked with pandas before. “I don’t think anyone is saying, ‘When I grow up, I’m going to inseminate a panda,’ ” says Mastromonaco. “There’s no textbook for us.”

To use the experience for future conservation efforts, the panda team evaluates the cubs at least three times per day and films them with a video camera in the playpen.

The knowledge hasn’t come cheap. The zoo will have to pay $200,000 in fees to China for the cubs’ birth ($100,000 each), and will soon spend another $200,000 per year to cover the cubs’ bamboo, on top of the annual $1.5-million cost of the adults. China doesn’t permit zoos to charge extra for visitors to see panda exhibits, and zoos in Atlanta, San Diego, Washington and Memphis have found that the cost of cubs outweighs the attraction for visitors within the first three years.

That clock starts ticking this weekend, when the cubs meet their adoring public for the first time. Animal behaviourist Gabriel Magnus has watched 10,000 hours of footage of all four pandas. He sat in the panda house, watching the panda-cam every day (he says he was never bored) as the tiny, naked pink things grew into the crowd-pleasers they have become. And you know what? He’s a little sad.

“I was there for that, and there’s this little part of me . . . ” his voice trails off. “It’s like they’re never going to be two [years old] again, and they’re going to go off to university.”

Feeding time for the cubs at the Toronto Zoo. Feb. 18, 2016. (Toronto Zoo)

EDITOR’S NOTE:

The print version of this story referred to the Toronto Zoo’s 2015 financial statement, which has not been released to the public, and speculated it would show impressive losses. On Mar. 10, Jennifer Tracey, the senior director of marketing, communications and partnerships, said the zoo had a balanced budget for 2015, achieved through a “number of initiatives” as well as money from a reserve fund, which was bolstered after a profitable year in 2013 and has a balance of more than $1 million.

CORRECTION, 17 March 2016: This story originally misstated the size of the twin pandas’ team of keepers; the pandas’ date of birth; the identity of the zoo official who hit Da Mao with a dart; and a detail surrounding Er Shun and Da Mao’s initial courtship. Maclean’s regrets the errors.