Bill Blair: The former top cop in charge of Canada’s pot file

That a former police chief is shaping marijuana legislation might suggest a bewildering about-face. But, as Shannon Proudfoot explains, that’s not how it works with Bill Blair.

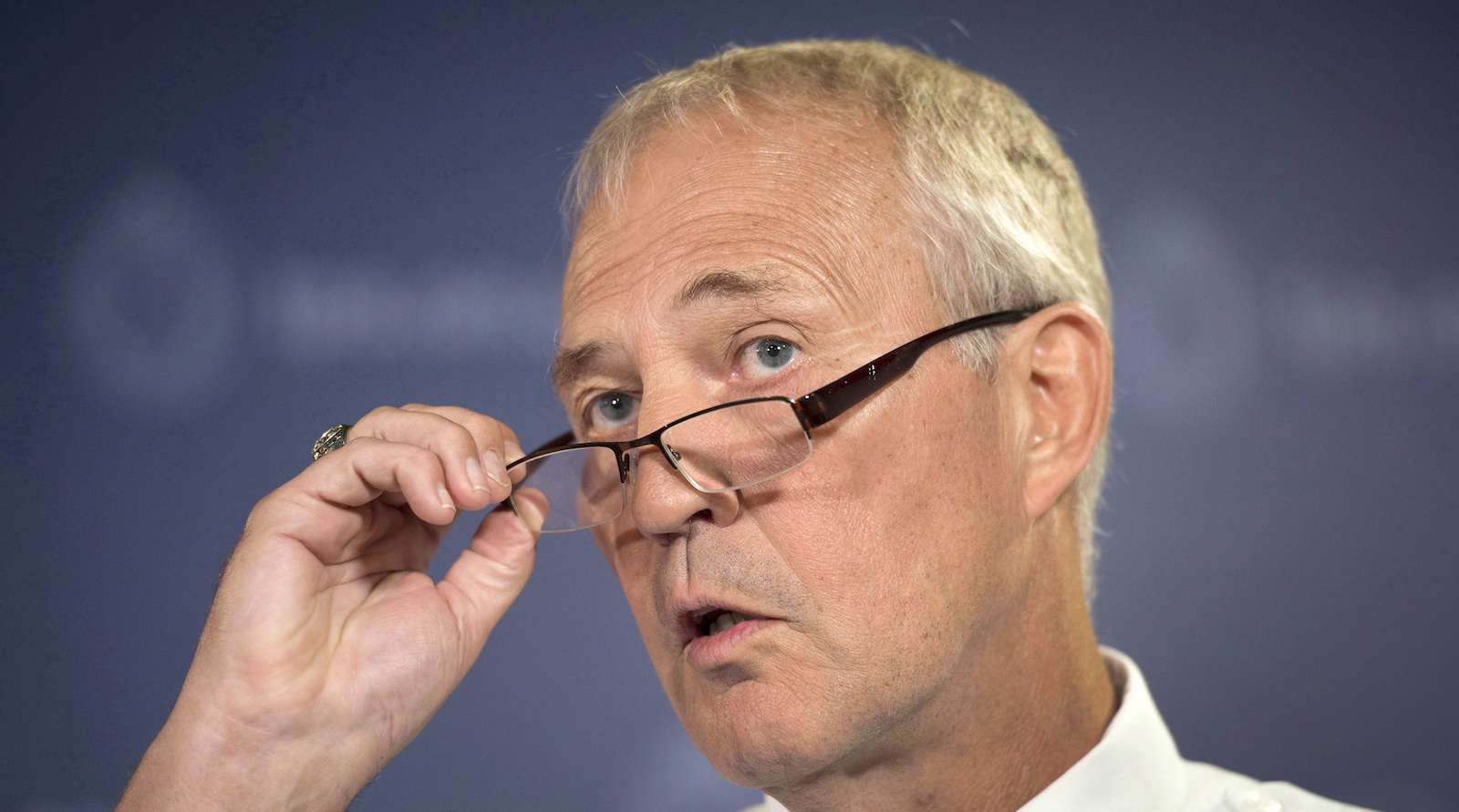

Former Toronto chief of police and current liberal MP representing the Scarborough Southwest constituency speaks with Maclean’s magazine to discuss preliminary structures of legalizing marijuana in Canada. (Photograph by Cole Garside)

Share

When Bill Blair worked undercover as a Toronto cop, his wife, Susanne, got accustomed to seeing him at home only every few days. If they had an appointment at the police credit union, she would use his pager to tell him when to meet her. Blair undercover is an interesting notion, because his natural appearance is such that he might as well wear a name tag that says, “Hello! My name is: a cop.” But for years on end, he would grow long hair and a scraggly beard, wearing a leather jacket and the attitude he said was the real secret to passing.

He also developed the ability to sleep standing up. He would meet Susanne—smiley, soft-spoken and as petite as he is towering—at the bank, and she would tell him to have a little nap until she nudged him. Blair would lock his knees, close his eyes and drop off. That’s when Susanne would notice the sidelong glances at this rough character by her side. One time, she couldn’t take it anymore and turned to the nearest bystander: “People, we’re in the police credit union,” she said. “He might be a policeman?”

Blair is, in some ways, once again incognito. He retired in April 2015 after 10 years as Toronto’s police chief, and immediately announced he would run for the Liberals in Scarborough Southwest. He won easily, garnering 52 per cent of the vote, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau subsequently named Blair parliamentary secretary to the minister of justice, tasked with shepherding through marijuana legalization. The nine-member task force that reports to him will release a report in November, and the government has said it will introduce new legislation in spring 2017. That a former top cop—a cop’s cop, at that, and the son of a cop—is handling the pot file in Canada suggests a certain reluctance, or even a bewildering about-face. But that’s not quite how it works with Blair.

He spent the early years of his career walking a beat in one of Toronto’s toughest neighbourhoods, and later pioneered what would come to be known as “community policing,” exporting that approach across the city once he occupied the chief’s office. Even before he made the switch to politics, Blair had decided that legalization and regulation of marijuana was the way to go. He says that was one of the things he and Trudeau discussed and found themselves aligned on in their first meeting. It turns out the quintessential cop bringing Canada’s most popular illegal drug out of the shadows is less a sharp left turn than a logical extension of his career so far. “I find people make a lot of assumptions about how I’ll think about something based on their traditional view of my role as a police chief,” he says. Once again, Bill Blair is in a position where he’s not exactly who he seems to be.

The joke in his family is that they’ve been breaking up fights and putting out fires in Toronto for the last century: his father, John, spent his career as a uniformed cop, and his grandfather—also John—was a firefighter. But Blair didn’t intend to become a police officer. He went to university, thinking he was headed for law school, and took a job with the police force while he was in school because money was tight and he figured he could learn a bit about criminal justice. It turned out he was good at it and loved the work, and so it became a 39-year career.

Related: Legalized pot is on the way

When Blair was new to it, he was out with his dad one day, both of them in uniform, when they came across a drunk man sprawled on the sidewalk. Blair, flush with new-cop adrenalin, just saw someone doing something wrong and ordered the man to be on his way. His dad waved him aside, reached down for the man’s hand and said, with great deference, “Come on, Friendly, let me help you up.” It was an encapsulation of the elder Blair’s gentle nature, and a revelation to his son: “I remember looking at my dad and thinking, ‘That’s the way you’re supposed to do it.’ ”

On his father’s advice, Blair began his career in 51 Division, which included the large and troubled public housing development of Regent Park. Blair and another young cop were assigned a foot patrol there; it was, in police parlance, a “very busy place.” Blair initially saw his job as tracking down bad guys and enforcing the law, but as he got to know the neighbourhood, he came to see the residents as decent people who just wanted a safe place for their families. His role was to make that happen. “We were the cops in the park,” he says. “It just became our place. Our park.”

After that, Blair did stints in drug enforcement, organized crime and undercover assignments. Susanne ran the show at home with their three kids, Matthew, Jonathan and Rachel. If she paged him, he knew it meant something important like a school concert—where he would slip in the back door of the gym, flash a thumbs-up and spirit himself away again—or a serious injury. When their oldest was about six, he tripped on a rug one evening and split his forehead open. Susanne left a message on her husband’s pager: “Matthew’s hurt himself. He’s okay, but he’s going to need stitches. If you’re not here in 10 minutes, I’m calling a cab.” She compressed the wound, changed her son into non-bloodied pajamas and, at about the nine-minute-and-50-second mark, was reaching for the phone to call a cab when she heard a squeal of tires. “He was gone so much when they were younger, but he always made it home for the really important things,” she says.

By 1995, Blair’s career was in its ascendancy at the same time that 51 Division was self-immolating, with Regent Park residents and the police feeling mutually under siege. He was scheduled to go into an intelligence job, but he asked to be sent back to the neighbourhood he thought of as his instead. “The joke of the day was that I was being transferred to the Valley of Career Death,” he says.

After a race riot sparked by a cop screaming a slur at a Regent Park resident, Blair went alone to a community centre, parked a chair at the centre of a roiling room and took questions. Next, he sent two of his best police officers to the school just to say hi. The first time they visited, they freaked people out so badly, the principal called Blair to ask what was going on; six weeks later, Blair found his cops in a classroom reading to the kids. He got rid of the whiteboard where the division tracked drug arrests with the assumption that higher numbers were better, even though violence was escalating, too. And he put everyone back into uniform, so they would be a visible presence in the neighbourhood rather than undercover looking for drug dealers. “Everything went—calm,” he recalls, gesturing at the top of his desk like he’s settling a crowd.

It was his reputation for a progressive approach and a deep understanding of the police service, the city and its diversity, that carried Blair into the chief’s office in 2005. “Mr. Blair took office at a time of great expectation,” says Alok Mukherjee, whose tenure as chair of the police services board, the civilian oversight body, paralleled Blair’s time as chief. “It was a time of great changes because there was low morale, anxiety, and a sense that some big changes were needed in how we were policing the city.” Blair’s father died 18 months before he became the chief. “He knew,” Blair says. “That’s what I said when I was sworn in: my father’s not here, but I’d like to think he knows.”

Related: Why buying pot has never been easier

The first half of his tenure was hugely successful: he decreed that half of the force’s hires would be women or visible minorities, improved the historically toxic relationship with the LGBT community, and moved the police graduation from a private setting to Nathan Phillips Square at noon hour, so Torontonians would know these were their cops. In every grad speech, Blair told his new officers to treat every moment as if the reputation of the Toronto Police Service rested on them doing the right thing, because it did. “I was bowled over, because that’s a very unique statement for a senior police officer to make. It implicitly suggests that police don’t do the right thing,” says David Miller, the mayor at the time. “That’s the first thing they heard from their police chief. I basically thought, ‘Wow. What a statement.’ Clearly the right thing.”

But the latter half of Blair’s time as chief was fraught. He was criticized for what was seen as his intransigence on carding—officers stopping citizens to log their personal information, which was disproportionately applied to non-whites—and for the handling of the G20 protests in 2010, when 1,100 people were arrested. “I would say that the G20 had a significant impact on the regard in which Mr. Blair was held in the community,” says Mukherjee. “People felt let down, and that feeling was there in the board also.” Miller, on the other hand, places blame at the feet of the “secretive and non-communicative” federal government that planned the summit. He believes Blair took the fall publicly for decisions that were not his (multiple police services and a federally run Integrated Security Unit were involved). “But it’s my town,” Blair says. “I’m responsible for policing and safety in Toronto. I wasn’t making the operational decisions that weekend, but it’s still my town and my responsibility.”

In 2013, when Blair confirmed that police had obtained a video of Rob Ford smoking crack cocaine, he drew the ire of the mayor and his city councillor brother, Doug, who launched a series of escalating public attacks. There was also disagreement between Blair and the police services board on how to implement budget cuts. Blair was unsurprised when his contract was not renewed a second time. But in conversation, he mentions several times that, on his watch, Toronto became the safest large city in North America, and that he was the only modern Toronto police chief to serve more than one term: that’s important to him.

Real retirement is simply not in his nature, so his post-policing options came down to the private sector or public service, and that was an easy choice. He says all three of the major federal parties courted him. NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair told him, “Jack said you’re one of us.” Blair had worked closely with Jack Layton on a host of Toronto community issues, and he took it as a compliment that Layton believed they were aligned. In the senior Liberal ranks, Blair knew Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin and Michael Ignatieff fairly well, but he didn’t know Trudeau at all. Someone with political experience advised Blair to look for a leader he could support and an outlook that matched his, because policy details come and go. He and Trudeau met for several hours, and Blair found his party banner. “We didn’t talk politics, we talked values,” he says.

One of the areas where they aligned was on marijuana. Blair had already concluded that the current state of affairs simply wasn’t working. Canadians are some of the world’s biggest pot smokers (44 per cent of adults say they’ve used it at least once, according to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health), and to Blair, the use among teens—CAMH says 26.5 per cent of Ontario students in grades 7 to 12 have tried it in the past year—is “quite shocking.” On top of that, the legal availability of medical marijuana has made criminal sanctions for recreational use “almost unenforceable,” he says. As police chief, Blair didn’t dedicate a lot of resources to enforcement, and he says most chiefs in Canada are similar; at street level, the average cop is not going to bother with someone who has a bit of weed in their pocket. But he’s well aware that doesn’t play out evenly. “I think there’s a recognition that the current enforcement disproportionately impacts poor neighbourhoods and racialized communities, and there’s something unjust about that,” he says.

In shaping the upcoming legislation, Blair’s priorities—which align neatly with current Liberal talking points—are keeping pot away from kids, doing a better job of explaining the public health risks to everyone and killing off the hugely profitable illegal trade for organized crime. Blair is not a fan of the approach Colorado and Washington have taken, which he sees as commercial models meant to maximize profits. In Canada, he wants to see any revenue reinvested in public education, research and rehabilitation.

Age is a particularly thorny issue to Blair. Research shows that marijuana use poses a risk to developing brains up to the age of 25, but in practical terms, setting the threshold at the age of majority for alcohol purchase makes sense—except that varies by province. Distribution is another conundrum. In Ontario, if pot were sold through the LCBO, an idea Premier Kathleen Wynne has floated, for instance, the LCBO’s slick advertising is an odd fit for the public health approach Blair wants to see, which is essentially strictly limited availability with many cautions attached. “Allowing it and promoting it are two very different concepts,” he says.

At the moment, Blair still occupies a peculiar blended role in Toronto. His constituency office is in a long, narrow storefront in a fading commercial strip not far from the Scarborough Bluffs. He designed the space himself, making the reception area an open office where his staff deal with constituents in the largest spaces, and tucking a tiny, windowless office for himself near the rear of the building. One day in early August, a man of about 60 emerged into the reception area, sobbing, with one of Blair’s staffers trailing him with a box of tissues. She offered a few words of comfort as she gave him directions to another office, then called to let the agency know he was on his way. This happens a lot; there’s a box of Kleenex on the visitors’ side of Blair’s desk, and he notes drily, “I don’t cry much.”

Scarborough Southwest is a very diverse riding, and while things have slowed a little now, right after the election, his office was getting requests for help with up to 30 immigration files a day. He knows many people are looking not for the MP, but the former police chief. “Three-quarters of the problems that come in here have absolutely nothing to do with the federal government. But I’ve kind of been in the problem-solving business my whole life, so I’ve said to [my staff], ‘No one will ever come in here and be told, ‘Sorry, that’s not our jurisdiction.’ We’ll help them with whatever it is.” That gives him a chance to return to one of the best parts of his old job: Blair loved showing up on people’s doorsteps when something went wrong, or appearing on TV to tell Toronto, “We got this.”

Leaving policing for politics has been an adjustment. “Frankly, I would have stayed the police chief forever,” he says. “I thought they’d carry me from it.” He misses the immediacy of the 6 a.m. calls every day, briefing him on what had happened in his city overnight. And for a man accustomed to going around the table, asking his staff what they thought and then making a call that would turn into action, the stretched-out deliberation and negotiation of politics is a shift. But he gets it: the issues are broader in Ottawa, and everyone needs to be heard. He thinks it’s “one of the coolest things in the world” to look up at Parliament Hill and realize he works there.

As chief, Blair viewed the buzzing sprawl of Toronto as a big quilt of neighbourhoods, and he tried to make his officers see it that way, too. Now, he’s coming to view the whole country the same way. Blair still speaks about his policing career in the present tense, and always says “we” when he talks about the force he left a year ago to stick-handle one of the most interesting policy challenges of this Parliament. Asked how he views the officers on Toronto’s streets now that they’re no longer his cops, Blair gently bats away the premise of the question. “They’re still mine,” he says. “They are, they’re mine.”