Canada’s next NAFTA ‘charm offensive’ won’t look like the last one

Canada’s pro-trade pressure campaign used to target mainly Republicans. With Democrats in control of the House, that now needs to change

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks during a press conference at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC, on October 11, 2017. (Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

When the Trudeau Liberals launched an ambitious, far-reaching and sustained pro-NAFTA campaign in response to Donald Trump’s strident skepticism of the trade deal, it was no Hawaiian getaway. Literally. America’s tropical outpost was just about the only corner of the country never visited by a Canadian official between Trump’s inauguration and the renegotiated deal. (Canadians did lobby Hawaiians on the mainland.)

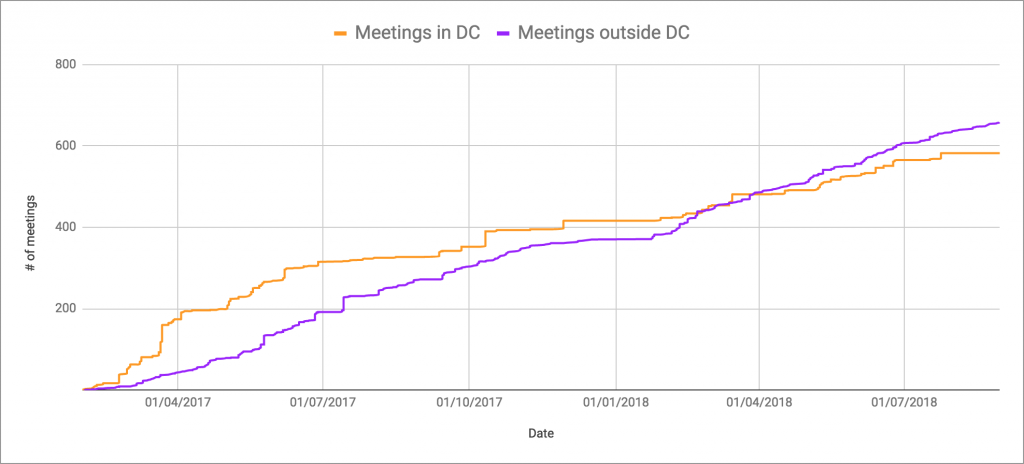

The vast breadth and precise character of the lobbying bonanza, nicknamed the “Maple” charm offensive, is revealed in documents released under access-to-information laws. Dozens of pages of spreadsheets detail more than 1,300 meetings between Canadian officials and American counterparts between Jan. 20, 2017 and Aug. 31, 2018, one month before the end of negotiations last September.

Liberals insisted they were extending their pressure campaign beyond the Canadian embassy’s familiar turf in Washington. They weren’t kidding. A Maclean’s analysis of the data shows a window into the sustained Canadian strategy that saw envoys meet key Americans where they live, not where they legislate. After an initial focus on Trump administration officials, the Canadians fanned out, seeking out major players—largely Republicans—outside of Washington D.C. Their approach has been vindicated—at least for now: on Sept. 30, Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland and Canada’s team of negotiators secured a deal that preserved Canada’s most important trade relationship while conceding none of the so-called “red lines” that would have skewed the partnership in favour of the U.S.

But the documents also offer a stark reminder of how drastically the political picture has changed since the U.S. midterm elections—and how Canada’s strategy must shift if it wants the new agreement to pass through a Congress where protectionist-minded Democrats once again wield power.

READ MORE: How Canada hopes to one-up the White House on NAFTA

Ambassador David MacNaughton’s advocacy focused largely on the capital, where 56 of his 70 meetings went down. Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland’s steady stream of visits to D.C. is reflected in the data. Meanwhile, Canada’s consular envoys in key cities, who amassed nearly 450 meetings, mostly stayed put. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, whose 86 meetings is second only to Freeland’s 92, neatly split his time between D.C. and the rest of the country. Transport Minister Marc Garneau, whose 47 meetings was the highest meeting count by any cabinet minister not named Freeland, held 40 of those tete-à-tetes outside Washington.

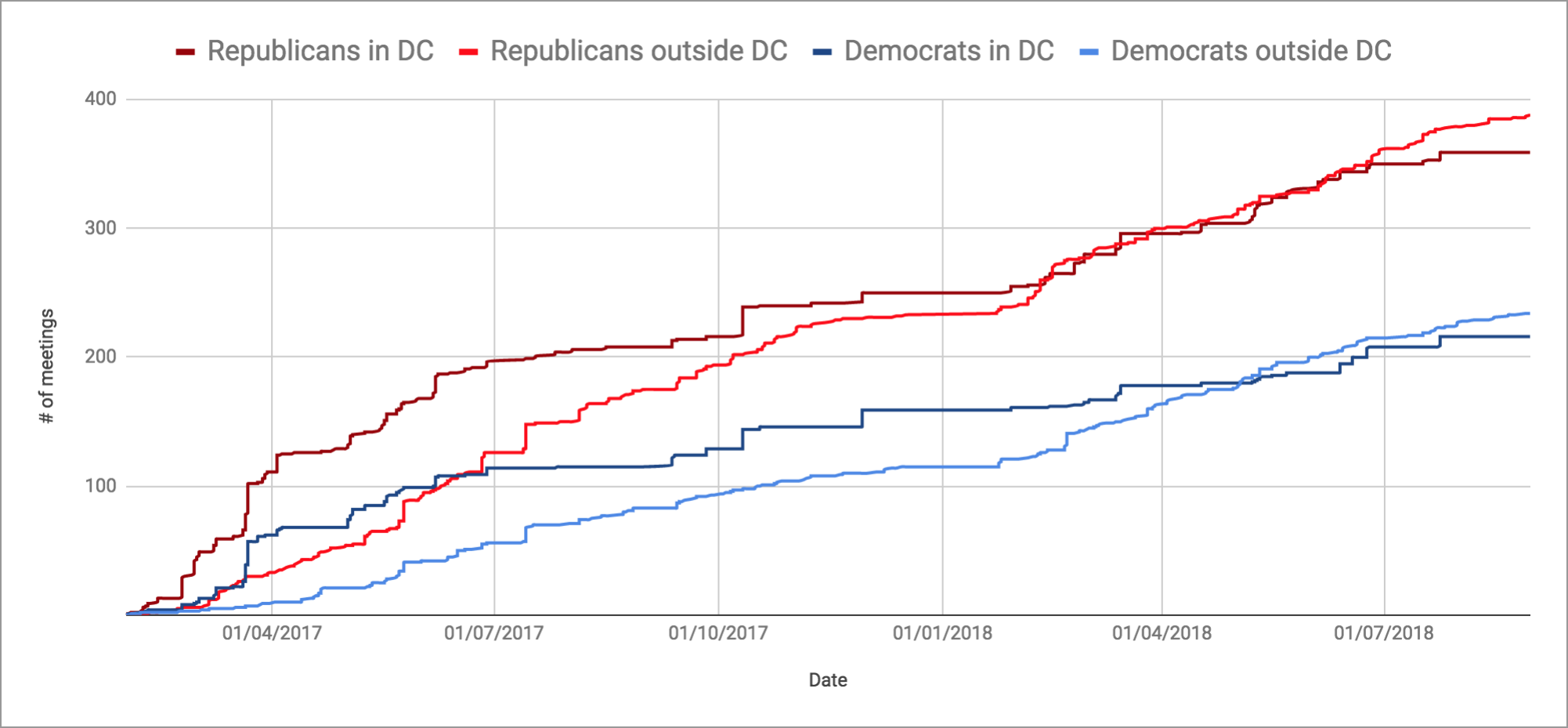

The Canadian brigade showed a consistent preference for Republicans, which accounted for more than 60 per cent of total meetings. Almost every premier, cabinet minister or regional envoy met with more GOP officials than Democrats. Twenty of former Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne’s 25 meetings, for example, were with Republicans. (David Alward, the consul-general in Democrat-heavy New England, was an exception.)

It’s no surprise the numbers skew so heavily toward conservative counterparts. Governors’ mansions lean Republican, as do state houses—not to mention both houses of Congress until this past January. Canada, which boasted “progressive” NAFTA modernization priorities, was always going to have to win over the right side of the political spectrum. But that was then. Democrats won back the House of Representatives in the midterm elections, and some vocal members of the majority caucus are the biggest free-trade skeptics south of the border. Even those whose districts are closest to Canada.

RELATED: How Canada’s NAFTA charm offensive hit a wall of confusion and apathy

“The Mexican government is a highly corrupt government. The so-called unions are highly corrupt,” says Brian Higgins, the Democratic co-chair of the northern border caucus, in an interview. In the thick of renegotiations, Higgins, who is ardently anti-NAFTA, insisted the two most northern partners should tag-team Mexico and force better labour standards. American negotiators were well aware of that hard line on Mexico, and the new deal forces Mexico to recognize unions and ensure their elections are free and fair, enforce the right to collective bargaining, and pay auto workers at least $16—vastly higher than average current wages.

Higgins isn’t convinced by any of that. “I don’t trust anything that is in writing,” he says. “Once these agreements are done, there’s a long, convoluted enforcement process that I think lacks teeth, lacks enforceability.”

No one will convince Higgins that free trade can improve Mexican working conditions. “How can anybody be confident that Mexico can be trusted and this agreement can be the vehicle through which labour and human rights and environmental standards are increased?” he asks. “The last 25 years has shown no measurable increase.”

Those are strong words from a member of the powerful House ways and means committee that ultimately gives the green light to trade deals. And he’s not alone. Neither party in D.C. has reached a clear consensus on NAFTA or its predecessor, but the Democrats’ progressive wing has wind in its sails—and it’s not clear where an energetic bunch of congressional rookies stand on the trade deal. Ilhan Omar, a first-term Democrat (and the first Muslim-American congressperson), is critical of NAFTA on her website and calls for enforcement mechanisms along the lines of what Higgins demands.

READ MORE: The USMCA explained: Winners and losers, what’s in and what’s out

The Canadians didn’t ignore skeptical Democrats. They lobbied Higgins eight times; Minnesota congressman Rick Nolan six times; and Higgins’s New York delegation colleague Paul Tonko five times. But meeting Democrats in D.C., in offices down the hall from where they cast their votes—and where they can throw a wrench into the new deal—were the Canadian charm offensive’s fourth priority, meriting only about 16 per cent of all meetings.

Christopher Sands, director of the Center for Canadian Studies at Johns Hopkins University, says it’s still worth cornering Democrats who aren’t sure which way to vote on the new trade deal—particularly because what constitutes effective enforcement, and how Democrats want those mechanisms to work, is in flux. “I think a lot of Democrats, partly because of Canada’s outreach, will be at least open to hearing what Canada has to say,” says Sands. “I would stay as engaged as possible.”

Freeland’s press secretary, Adam Austen, was tight-lipped about the Canadian strategy—but in a statement, he did note the controversial tariffs Trump levied against Canada under “national security” provisions of a nearly 60-year-old trade law. Wrote Austen: “We will continue to promote the importance of Canada-U.S. trade and to advocate for the removal of the illegal and unjustified tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum.”

The charm offensive has always faced strong headwinds in the form of political gridlock and nasty grudges in Washington, and Sands counts several factors that could significantly delay U.S. ratification of the deal. The legislative process must begin in the House, where Speaker Nancy Pelosi controls the agenda. In his 2019 State of the Union address, Trump did urge Congress to ratify the deal. But Pelosi can’t move until the White House delivers the text of the enabling legislation. And a separate analysis by the U.S. International Trade Commission, which could swing votes, was set back several weeks by the latest government shutdown. If Trump grows frustrated, he always wields the threat of unilateral withdrawal from NAFTA, which could force Democrats to either accept the new deal or face the uncertainty of no NAFTA at all. But the Democrats could retaliate by seeking a court injunction to prevent that withdrawal, which could add months of delays to any effort to ratify.

Even if Pelosi marshals the deal through Congress at a relatively brisk pace, says Sands, the Senate would then have to consider it own bill—and that could stretch the process into 2020. That’s an election year, and skittish Democrats could choose to hold out for a Democrat in the Oval Office who might see things their way on trade.

Of course, Trump could win re-election and even take back the House, once again disrupting the process and forcing everyone to start from scratch. Canadians who want to close the book on the whole ordeal could lose their minds gaming out every possible scenario. For now, they can only hope their charm brings good luck.