Hey America, this is how you do a leaders debate

As you watch Trump debate Biden you might be wondering if there’s a better way. So we present to you Canada’s iconic and admirable 1984 election debate.

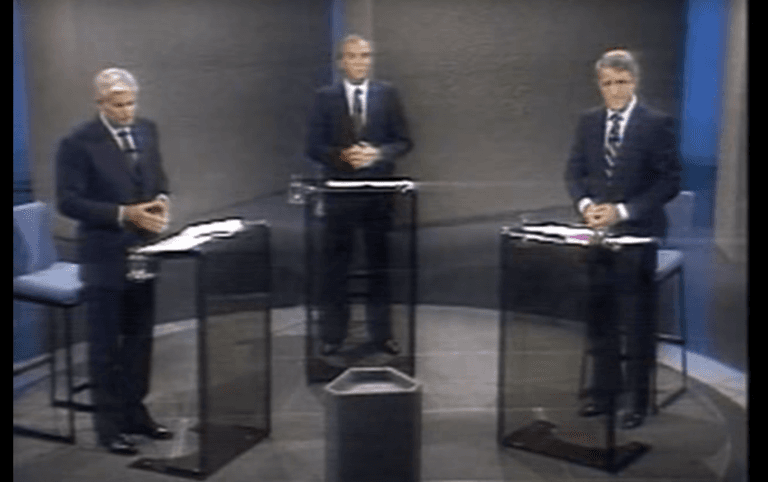

(YouTube/CanuckPolitics)

Share

Hey, America. As you watch the first presidential debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, you might be wondering if there’s a better way. The Republican and Democratic standard-bearers typically engage in just so much grandstanding, boasting, spinning and, particularly in one candidate’s case, outright lying from their perches onstage in front of the eyes of the world. Surely, there’s a better way, isn’t there?

In this corner, we have a high opinion of the recent Maclean’s debates in 2015 and 2019. But tonight, cast your mind back to the middle of the 1980s. Ronald Reagan’s re-election campaign was in full swing. With two months to go until his triumph, and about a month before Reagan took on Walter Mondale in their first showdown, Canada’s three party leaders sparred in a debate for the ages. John Turner, the Liberal leader who’d been prime minister for just three months after Pierre Trudeau’s retirement, hoped to win his own term in power. Brian Mulroney, the Tory leader for just over a year, hoped to prove to voters that he was the real deal. And Ed Broadbent, the NDP leader, hoped for an electoral breakthrough for his social democrats. The debate had everything: future governor general David Johnston as moderator, a genuine focus on public policy that still managed to be interesting and, of course, an eventual knockout blow that changed the course of the election.

Here’s why a dose of Canadian debate should be your palate cleanser as Trump and Biden open their own series of televised face-offs.

They stuck mostly to facts

Mulroney attacked Turner’s record as finance minister, the PM’s last job before leaving politics for almost nine years. The Progressive Conservative leader complained that Turner’s time as steward of the public purse, between 1972 and 1975, was rife with poor performance. “In terms of profligacy, it is widely known that in your short period as minister of finance, inflation doubled, interest rates almost doubled, the federal debt doubled, and the $600 million surplus was transformed into an operating debt of $4 billion.”

In fact, interest rates did almost double from 4.75 per cent to 8.5 per cent, and the inflation rate did more than double from 4.8 per cent to 10.7 per cent. The national debt didn’t double, but the accumulated federal deficit did increase from $23,980 in 1972-73 to $41,517 in 1976-77—though that was more than a year after Turner’s departure.

In his reply, Turner claimed credit for the last two federal budget surpluses to that point. And he said that even though an economic downturn forced the government to increase expenditures–which produced a $3.5 billion deficit—the average budgetary deficit over his four years was under $750 million. In fact, Turner was correct that no finance minister had matched his modest surpluses. He was right that his final deficit added up to $3.5 billion, too. Our calculations are that his average deficit, however, was $965.75 million (that’s based on these fiscal tables).

They gave each other credit

The journalists asking the questions challenged both Turner and Mulroney, whose annual incomes were far above the national median, to explain to voters how they could possibly identify with the day-to-day anxiety faced by middle-income families who needed to pay the bills. Both men emphasized their modest means growing up—Turner in Ottawa, Mulroney in Baie-Comeau, Que. “I’m always uneasy talking about this sort of thing. And I don’t think I want to get into a contest of humility with Mr. Mulroney,” said Turner. “I’ve worked hard, as Mr. Mulroney has, I’ve had some luck in life, I’ve been successful.”

They still produced high drama

The evening’s most famous moment came near the end, during the portion of the 90-minute debate when Turner and Mulroney were responding to each other’s answers. Turner had taken heat for approving a deluge of federal patronage appointments that handed plum gigs to Liberals. Turner had agreed to abide by a slew of appointments made by Trudeau on his way out of office. A year before the election, Mulroney had joked he would find jobs for Progressive Conservatives until “there isn’t a living, breathing Tory left without a job in this country.” He later apologized for the remark. His exchange with Turner arguably turned the tide of the election.

Mulroney: “I’ve had the decency to acknowledge that I was wrong in even kidding about it. I shouldn’t have and I’ve said so. You, sir, at least owe the Canadian people a profound apology for doing it. The cost of that, $84 million … We could pay every senior citizen in this country on the supplement an extra $70 at Christmas rather than pay for those Liberal appointments.”

The Tory leader demanded that Turner apologize for the patronage. But the PM wouldn’t budge.

Turner: “I’ve told you, and I’ve told the Canadian people, Mr. Mulroney, that I had no option.”

The moderator, David Johnston, was about to move on to the next question. But Mulroney interjected.

Mulroney: “You had an option, sir. You could have said I am not going to do it. This is wrong for Canada, and I am not going to ask Canadians to pay the price. You had an option, sir, to say no. And you chose to say yes to the old attitudes and the old stories of the Liberal party. That, sir, if I may say respectfully, that is not good enough for Canadians.”

Turner: “I had no option. If I was able…”

Mulroney: “That is an avowal of failure. That is a confession of non-leadership. And this country needs leadership. You had an option, sir. You could have done better.”

Mulroney went on to a landslide majority victory that reduced the Liberal caucus to 40 seats—and the NDP close behind at 30.

They always admired each other

Turner, Mulroney and Broadbent went at it again in the 1988 election, which produced a reduced Conservative majority and a larger Liberal caucus. When Turner died this year at the age of 91, however, both Mulroney and Broadbent expressed admiration for their former foe—with no hint of malice.

Mulroney told CTV News: “John Turner was a gentleman in politics … I found him to be a very tough opponent and very vigorous opponent, but a gentleman in Canadian politics at all times.” He told CBC News: “He was a great House of Commons man. He believed in democracy; he believed in our Parliamentary system. In his career he performed brilliantly in the high portfolios that he was given.”

Broadbent released a statement on Twitter: “John Turner, of all the party leaders I have known, had the deepest respect for Parliament and for its democratic rules and procedures. He was an immensely civilized man. Canada will miss him. My warmest wishes and condolences to his family on this difficult day.”