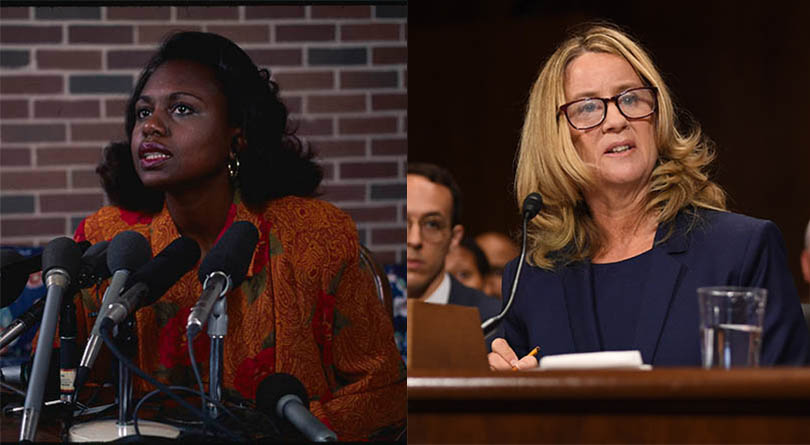

How Christine Blasey Ford and Anita Hill walked the impossible knife’s edge

Shannon Proudfoot: ‘Separated by 27 years and a social landscape that has supposedly shifted on its moorings, two remarkable testimonies share inescapable parallels’

Share

In the most surface ways, they are a study in contrasts.

One was a young lawyer when she withstood the steady stream of sexual harassment and objectifying humiliation she said her boss barraged her with. By the time she appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991 to tell her story, she was a law professor—still young, achingly earnest, crisply professional, exhibiting the kind of glass-smooth calm that suggests nerves tamed by an act of will.

The other was a teenager—a child, really—when she says another teenager she knew climbed on top of her, pawed at her clothes and body, smothered her screams with his hand and laughed drunkenly through it all with a friend looking on. By the time she, too, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee to tell them this was an act their nominee for the Supreme Court had committed, she was an accomplished research psychologist in her early 50s. She opened her testimony with a self-possessed joke about needing caffeine, confidently plowed through documents she was asked to vet on the spot, and unspooled her story in a voice that frequently warbled with boxed-up tears, yet she remained completely, calmly in control of her narrative.

MORE: Watch Anita Hill’s testimony against Clarence Thomas in 1991

And still, separated by 27 years and a social landscape that has supposedly shifted on its moorings, the remarkable testimonies of Anita Hill and Christine Blasey Ford share striking, inescapable parallels. These echoes speak not just of a society that hasn’t changed nearly as much as it claims—nearly as much as seemed inevitable—between Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh, but also to the contortions of women walking an impossible knife’s edge.

You must be polished enough to seem credible, but don’t ever look uppity. You should be emotive so as to elicit sympathy and be believed, but never shade into hysteria. You must have an answer for everything, except when that seems a little too perfect to be trusted. You cannot be some embittered crusader, but also why did you put up with any of this or stick around? You must account for every dime and syllable of support you have received in order to demonstrate your pristine motives, and you should have told just the right number of people about what happened to you, at just the right time and for just the right purposes.

And, most of all, you must make a case—still—for why you are troubling everyone with all of this in the first place, why this thing that upended your life is worth the inconvenience of making everyone listen, much less why it should be considered a serious mark on the record of a man poised to vault up several rungs on the ladder.

Hill and Ford have both clearly absorbed the same rulebook as so many other women. And garbled as it is, that set of codes and expectations set up moments of remarkable, surreal, maddening parallel between their decades-apart Senate hearings.

Both women said—more than once, and in very similar language—that next to the attacks themselves, revealing them to the world was the most difficult experience of their lives.

And both Hill and Ford seemed to have internalized the criticism and doubt they knew would be lobbed at them for coming forward. Even as they unspooled their stories, they were nearly litigating against themselves, anticipating how their perfectly rational and reasonable decisions might be critiqued, and justifying them as they went.

“Telling the world is the most difficult experience of my life, but it is very close to having to live through the experience that occasioned this meeting,” Hill said in 1991, her eyes flicking briskly from the prepared remarks on the page in front of her to the men she was testifying before.

She may have used “poor judgment,” she conceded—by which she meant, she decided that she couldn’t afford to destroy her career and incur the wrath of a man who seemed to hold it in the palm of his hand by telling him off or reporting him. A few seconds later, she added of her decision to go public, “It would have been more comfortable to remain silent. I took no initiative to inform anyone. But when I was asked by a representative of this committee to report my experience, I felt that I had to tell the truth. I could not keep silent.”

ALSO: Brett Kavanaugh can’t squeeze in a word at his own confirmation hearing

Ford, for her part, in a voice hoarse with emotion, explained, “Apart from the assault itself, these last couple of weeks have been the hardest of my life. I have had to relive my trauma in front of the entire world, and have seen my life picked apart by people on television, in the media, and in this body who have never met me or spoken with me.”

And she, too, just a few sentences later, felt compelled to justify why she had spoken up in the first place. “My motivation in coming forward was to provide the facts about how Mr. Kavanaugh’s actions have damaged my life, so that you can take that into serious consideration as you make your decision about how to proceed. It is not my responsibility to determine whether Mr. Kavanaugh deserves to sit on the Supreme Court. My responsibility is to tell the truth.”

Both women, too, were visibly distressed by the most granular details of their stories—the sorts of things that lodge in the memory like shards of glass.

The very few times Hill’s composure frayed during her testimony arrived when she had to spell out the graphic nature of the comments she said Thomas subjected her to. There was a self-protective flatness in her eyes when she told the committee how the judge would brag about the size of his genitals. “He also spoke on some occasions of the pleasures he had given to women”—here she paused for a second or two, taking an audible breath before continuing with distaste. “With oral sex.”

Later, she referred several times to “the incident with the Coke can.” It was a moment she’d already explained fully, but Democrat Joe Biden, then chairman of the committee, pressed her until she reluctantly reiterated that Thomas had inquired, when they were alone in his office, who had left a pubic hair on his drink. A few moments later, it was obvious that Hill was skating around the name of a porn actor Thomas had enthused about, until she was pressed for a specific answer. She looked down at the table in front of her, blinked once very slowly and then supplied the humiliating answer: “Long Dong Silver.”

On Thursday, Ford was asked several times by Democrats what was inescapable in her memory about the sexual assault she said Kavanaugh had subjected her to. She talked about the spaces where it all happened: the bedroom she was shoved into with a bed on the right side and the door locked behind her; the bathroom across the hall that she fled to after she managed to escape; the narrow stairwell she said Kavanaugh and his friend Mark Judge “pinballed” down after she escaped them.

But more than anything, what stayed with her was their drunken mirth while she feared she was going to be raped or accidentally smothered to death. “The uproarious laughter between the two,” she said, her voice creaking with unshed tears. “And their having fun at my expense.” Democrat Patrick Leahy clarified, “And you were the object of the laughter.” Ford leaned toward the microphone, “I was underneath one of them while the two laughed. Two friends having a really good time with one another.”

But Ford, at least, got one grace note that Hill never did, and it formed one of the most emotionally striking moments in a day with so many that it wrung many observers out.

“I have found your testimony powerful and credible,” Democrat Richard Blumenthal told her carefully. “And I believe you.”

He praised her for giving other victims courage to speak out—as he said they had been doing in droves, contacting every one of his colleague’s offices—and for enlightening men to listen with respect to survivors like her. Then Blumenthal read a quote from Lindsey Graham’s own book on his career as a trial lawyer: “I learned how much unexpected courage from a deep and hidden place it takes for a rape victim or sexually abused child to testify against their assailant.”

Blumenthal read the whole quote through a second time, and that is when Ford’s face crumpled. “If we agree on nothing else today, I hope on a bipartisan basis we can agree on how much courage it has taken for you to come forward, and I think you have earned America’s gratitude,” he told her.

Ford stared down at the table in front of her, eyes welling up and chin trembling, then looked up toward the committee dais. She mouthed two silent words: “Thank you.”