If this election is the ‘most important,’ which one was the least?

The leaders would have you believe every vote is a battle for the soul of the nation. History tells us otherwise.

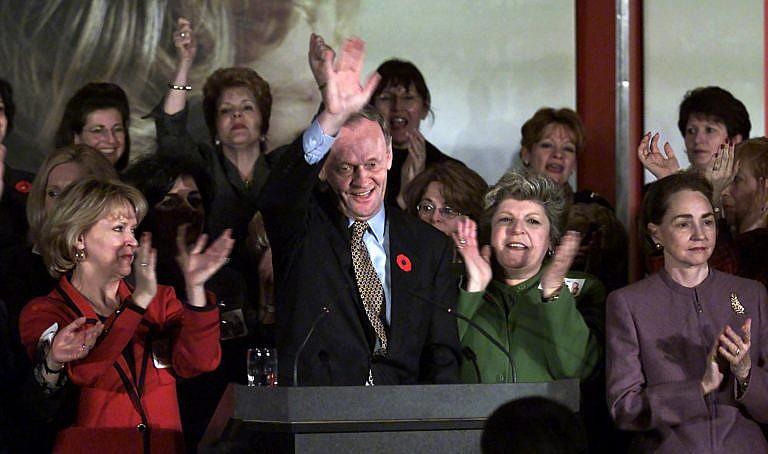

Prime Minister Jean Chretien, with his wife Aline, during a campaign stop in November 2000.(Fred Chartrand/CP)

Share

This is, in the view (primarily) of politicians trying to get their voters to vote, the most important election of our lives. To the guy who called the election, this moment is the “maybe the most important since 1945 and certainly in our lifetimes.”

Voters seem to agree that this election is at least more important than the previous one, an Angus Reid Institute poll found in August. However, the pollster noted, Canadians thought the same thing in 2019, as well as in 2015.

Federal elections are the hinge on which democracy and government turn, each one holding massive potential influence (for better or worse) over Canada’s trajectory, and offering significant policy reforms. In the thick of a campaign, even the relatively dullish ones seem to brim with intensity and possibility, birthing endless what-if outcomes.

But rhetoric be damned, they can’t all be the most important election ever. Which prompts Maclean’s to ask: What would be the least important election of our lifetime?

To help us search for Canada’s less consequential elections, the dramatic duds and showdowns that hardly qualify as show-stoppers, we put this question to some political historians and other veteran campaign watchers. There was only one election to get multiple votes from our experts—one that elected a new Prime Minister, to boot. But there were several potential candidates for this dull crown. And it was with some trepidation our experts weighed in, given that their careers have revolved around decoding the fascination with and meaningfulness of each and every election.

Here they are, from the fewest seat flips to the most:

1940: Another majority for William Lyon Mackenzie King’s Liberals, up six seats. Robert Manion’s “Conservatives” stay flat.

Why it’s unimportant: “The outcome was not in doubt. Canada was at war and the Conservatives had no chance of winning,” says Nelson Wiseman, professor emeritus of political science ant University of Toronto. With the Second World War well under way, and Canadians rallying behind three-time winner King, the Conservative leader didn’t even run under its own banner—Robert Manion temporarily rebranded his party “National Government” with a promise to run a coalition government. He lost his own Northern Ontario seat, and King triumphed with 179 of 245 seats, a record-busting Liberal finish that followed one nearly as good in 1935. Wartime government marched on.

1965: A second minority Lester B. Pearson’s Liberals, up three seats. Tories up 4, NDP up 4, Social Credit down 19.

Why it’s unimportant: This may sound familiar today—Pearson dissolved Parliament 2½ years after beginning his term hoping for a majority that he failed to secure, notes U of T’s Wiseman. Tommy Douglas’ NDP remained strong enough to prop up his government for another three years. “A consequence of the 1965 election was John Diefenbaker’s demise as Conservative leader, but the election itself didn’t change parliamentary dynamics,” he notes. With that status-quo House of Commons makeup, the Pearson government passed major legislation such as Medicare, though he’d promised major health reform back in 1963.

2000: A third majority for Jean Chretien’s Liberals, up 11 seats. Canadian Alliance up six, Bloc Québecois down six.

Why it’s unimportant: Chrétien called an election early, barely three years into his term, to catch new Opposition leader Stockwell Day off guard. It worked with predictable effect. There may have been memorably goofy Day moments like his wielding a “No two-tier heath care” sign during the debate. But the incumbent was forgettably capable. “Chrétien was utterly unsurprising, deliberately so, with no ambition grander than muddling along,” says Susan Riley, a veteran political columnist formerly with the Ottawa Citizen. It again seemed like more of an opposition slugfest amid a split between conservative parties and the Quebec nationalists skating on their own. “During the Chrétien decade, it often felt like the country was on cruise control and elections were only brief interruptions,” Riley says.

2008: A second minority for Stephen Harper’s Conservatives, up 16 seats, Liberals down 18 seats, Bloc up one, NDP up seven.

Why it’s unimportant: For Harper, this was shades of Pearson’s 1965, Wiseman says. “In both cases, prime ministers (Pearson and Harper respectively) led minority governments. They dissolved Parliament in search of a majority. In both cases, they failed.” Most of the excitement came after the election, with Liberal leader Stephane Dion bidding to cobble together a coalition with the NDP and support from the Bloc. But that attempt collapsed and the Conservatives continued apace.

1953: A fourth successive majority for Liberals under Louis St. Laurent. Liberals down 22 seats, Progressive Conservatives up 10, Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) up 10.

Why it’s unimportant: The same result, again. “That one wasn’t even a contest,” says Ken Carty, former chair of Canadian studies at University of British Columbia and author of 2015’s Big Tent Politics: The Liberal Party’s Long Mastery of Canada’s Public Life. “It simply reconfirmed the long-recognized position of the Libs as Canada’s natural government party.” The socialists gained seats but their popular vote declined, suggesting they wouldn’t become a postwar force, Carty argues. He adds a point that may perk contemporary ears: “It was a summer election, perhaps not the best time to stir Canadians.”

1979: Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals defeated; Joe Clark’s Tories win, up 38 seats. Liberals down 19, NDP up 9.

Why it’s unimportant: First, why it was supposed to matter. This was a change election, with the young Clark’s Tories asking Canadians, “Do you want four more years like the last 11 (under Trudeau)?” longtime pollster and consultant Allan Gregg recalls. This was the same time that Margaret Thatcher rose in Britain, and Ronald Reagan was about to sweep into the White House; time seemed ripe for Clark to become a big player in the new conservative decade. But he didn’t. “Nine months later, after ‘governing like we have a majority’ the Clark government was defeated first in House, and then on the hustings, and it was like nothing ever happened,” Gregg says, with some pain—1979 was the first election he participated in.

There was some agreement on the one-and-poof Clark election’s relative unimportance to history. “Before anyone could blink, Pierre Trudeau was back, unchastened and not evidently interested in the job,” Riley says.

Constitutional talks resumed from the Liberals’ past term, as did Trudeau’s budget management style, says Penny Bryden, a history professor at University of Victoria. “None of the innovations that Clark proposed really ended up being implemented or making a difference.”

But, Bryden adds, 1979 did offer all those disillusioned with the first PM Trudeau a chance to vote their displeasure, even if the results didn’t stick. She struggled with this exercise. “The problem is that I care about politics, so I can’t think of an election that wasn’t important in letting people make a decision about government,” she says.

To some Canadians, every election might seem unimportant, Bryden reasons: “Just the shift from one white man to another, one set of ideas that inevitably benefit an elite to another.” But they all either changed the government, or had key policy positions fought on or vindicated. Though 1979 was her initial choice, Bryden ultimately felt stumped. “Even if the timing of these elections is questionable, once you’re in the middle of one, it becomes important.”

So whether or not the 2021 contest brings forth a new Prime Minister, it may go down as a very important election. Or an irrelevant one. Maybe ask us in 20 years.