Nelson Mandela conquered apartheid, united his country and inspired the world

His remarkable journey was one of the great sagas of our time

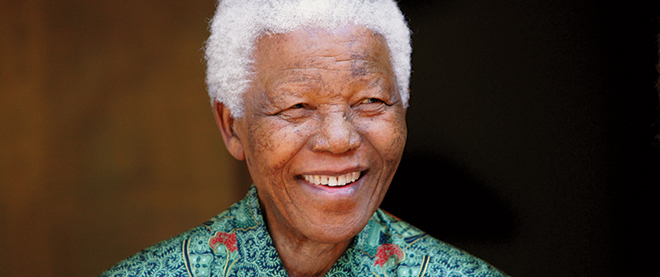

Mike Hutchings/Reuters

Share

Yanelisa Khandawuli has no doubt about what Nelson Mandela has meant to South Africa. “He is like Jesus,” says Khandawuli. “He went to jail for us, and set us free.” Khandawuli, a 20-year-old resident of Qunu, where Mandela grew up, is sitting near the village shabeen, an informal bar, on a white plastic chair, her one-year-old son swaddled to her back with a blue plaid blanket as she plucks feathers off dead chickens she will later sell. The house that Mandela built upon his release in 1990—after serving 27 years, six months and six days of a life term for treason against the apartheid regime—is 200 m away, on the other side of a two-lane highway. The most striking part of the building is its design: The red-brick villa is an exact replica of the warder’s lodge at Victor Verster prison, the minimum-security facility where Mandela spent his final months in captivity. The location of the house was equally deliberate, chosen, Mandela said, because “a man should die near where he was born.”

“It was in these fields,” he wrote in his autobiography, “that I learned how to knock birds out of the sky with a slingshot, to gather wild honey and fruits and edible roots, to drink warm, sweet milk from the udder of a cow, to swim in the clear, cold streams, and to catch fish with twine and sharpened bits of wire.”

But things did not unfold as he had envisioned. When the father of modern South Africa died on the evening of Dec. 5, at the age of 95, it was at his other house, in a leafy suburb of Johannesburg, some 900 km away. In his frail final years, Mandela had been in and out of hospital. His last public appearance was at the final of soccer’s World Cup in July 2010, and there hadn’t been a picture of him since April. According to some reports, the former president had been comatose since the summer. There was an ugly and very public battle among his children and grandchildren over his final resting place. And although the official line was that he was “recovering,” it was clear to all that he was actually slipping away.

The reaction was more of relief than of shock when Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s current President, took to the country’s airwaves shortly before midnight to announce that Mandela’s fight had finally ended. “He is now resting. He is now at peace. Our nation has lost its greatest son. Our people have lost a father,” said Zuma. “His tireless struggle for freedom earned him the respect of the world.

His humility, his compassion, and his humanity earned him their love.”

Within the hour, a large crowd had gathered in the street outside the house where he died. Some were dressed in pyjamas, others wrapped in blankets. They lit candles and added flowers, cards and keepsakes to a makeshift memorial. And they sang: songs of past struggles and Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika (God Bless Africa), the unifying national anthem of the new South Africa he bequeathed them.

“Nelson Mandela brought us together, and it is together that we will bid him farewell,” Zuma vowed in his address to the country. But the outpouring of emotion for a man whose transformation from outlaw to leader was one of the great sagas of the 20th century was truly global. “We have lost one of the most influential, courageous and profoundly good human beings that any of us will share time with on this Earth,” said U.S. President Barack Obama, who traces his own political awakening to the fight against apartheid. “He no longer belongs to us—he belongs to the ages.” Prince William, attending the London premiere of a new movie about Mandela’s life when the news broke, called it sad and tragic. “We were just reminded what an extraordinary and inspiring man [he] was.”

Nelson Mandela’s political odyssey took him from rural royalty, to militant freedom fighter, to international defender of human rights. His one-term presidency, from 1994 to 1999, was an exercise in magnanimity. The man they affectionately called “Madiba” was South Africa’s moral authority, a tireless negotiator wielding the irrevocable power of history on his side, who could see eye-to-eye with anyone in his divided country. He was as regal as a Xhosa king, as tenacious as an Afrikaner sergeant. And his decision to embrace reconciliation, rather than revenge, set a path for his nation and an example for the world.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination,” Mandela said in his most famous speech, an address from the dock during the 1964 Rivonia Trial—named for the location of the Lilieslief farm—for state sabotage. “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Rolihlahla Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in the tiny village of Mvezo, in South Africa’s southeast, but moved to nearby Qunu when he was one. The villages are in the Transkei, one of South Africa’s most remote regions, an area known for its pastoral beauty, with rolling green fields, deep valleys and curving rivers. The round homes called rondavels, painted straw yellow and robin’s-egg blue, dot the landscape. Rolihlahla, Mandela’s given name, means “shaking the branch of a tree”—or troublemaker. He would go on to shake South Africa to its core.

[mlp_gallery ID=155]

Many trace Mandela’s leadership style—to listen and take everyone’s opinion into account before giving his own—to the traditions of the royal court, where he was raised. His upbringing, at the heart of a royal court of the Thembu tribe and, later, at elite Wesleyan schools, also gave him an unusual confidence for a rural, black South African of his generation.

Mandela was the great-grandson of a Thembu king, and his earliest lessons were fireside tales of heroic African warriors and their frontier wars with the British. Mandela was a lesser royal, he always stressed, and was never in line for the Thembu throne; but after his father Henry’s death, when he was nine, he left his mother Nonqaphi’s home, to be raised by the acting Thembu king, Jongintaba. According to tribal custom, Jongintaba treated Mandela as a son; still, Mandela was aware he was an outsider, which some believe spurred his later ambition. He was such a serious boy, his friends nicknamed him Tatamkhulu—“grandpa.” By then, he’d acquired an English name: Nelson, a likely nod to the British admiral, bestowed on him by a schoolteacher.

Education was always one of Mandela’s priorities, says Chief Tembinkosi Mtirara, whose grandfather was Justice, one of Mandela’s closest friends growing up. Mtirara met Mandela when he had his University of Transkei admission letter in hand. “He said, ‘First thing tomorrow, you come to my office, I’ll sign your cheque and then you should go to school.’ That was our first encounter.”

Mandela’s teachers at Clarkebury Boarding Institute, a Wesleyan college, and then at Healdtown, were British expatriates, not South Africans. At Clarkebury, where he became a school prefect, he wore shoes for the first time: “That first day,” he has said, “I walked like a newly shod horse.” Boxing and distance running replaced his boyhood games of stick-fighting, which taught him, he’d later say, to “defeat opponents without dishonouring them.”

He went on to tiny University College of Fort Hare, becoming one of 50 black southern Africans the school accepted every year. But before he could graduate, he was expelled in 1939 for leading a student protest, along with his friend Oliver Tambo. He returned home briefly before decamping for Johannesburg at 22, escaping a marriage his guardian had arranged for him.

“All roads lead to Johannesburg,” Alan Paton wrote in his novel, Cry, the Beloved Country. “If the crops fail, there is work in Johannesburg. If there are taxes to be paid, there is work in Johannesburg. If there is a child that must be born in secret, there is Johannesburg.” Black and white, they came by the thousands, some dressed in rags and blankets, to escape poverty, to find work below ground, in the booming mines that surround the city, or high above it, in the glass towers dotting the skyline. Among them was a young Mandela.

It was a sobering step. A few weeks earlier, Mandela had been among the African elite, enrolled in university, with a royal career ahead. Suddenly, he was penniless and unemployed, an unknown in a cold, violent city.

Mandela had decided to become a lawyer. A chance meeting with Walter Sisulu—a black estate agent who had an office in the city centre in the days before Johannesburg become strictly segregated—would shape his destiny in more ways than one. Sisulu, then 28, was six years his senior, another transplant from the Transkei. Sharp, warm and at ease in the big city, he mentored Mandela, and would ultimately serve two decades in prison beside him. Sisulu saw in Mandela “a man of great qualities,” and took him to meet Lazar Sidelsky, a lively, Jewish lawyer with a pencil-thin moustache, who took black clients. Sidelsky agreed to take Mandela on at his practice. By day, Mandela clerked for Sidelsky. After hours, he studied law by candlelight—the University of the Witwatersrand’s only African student.

Sidelsky, who “practically became an elder brother,” Mandela once said, urged him to steer clear of politics. (“You didn’t listen, and look where you ended up!” Sidelsky would tease him, decades later, on a prison visit.) But, with Sisulu as his guide, Mandela was quickly drawn into the sphere of the African National Congress, then a decades-old organization fighting for greater rights for South Africa’s black population. In 1944, Mandela and a group of young, Jo’burg intellectuals who dubbed themselves “the graduates,” helped found the ANC’s Youth League.

There, he reunited with Oliver Tambo, his old classmate and agitator. After convincing him to drop teaching for law, they founded Mandela and Tambo, the country’s first black law firm. Tambo was the workhorse, Mandela the showhorse. With his sharp mind and good looks, Mandela had become a leading figure in Johannesburg’s small, black elite. His incredible ambition was matched only by his arrogance.

His private life, however, was complicated. After a whirlwind romance, he’d married Evelyn Mase, a cousin of Sisulu’s with whom he would have four children (one, a daughter, died in infancy). But over the years, they were pulled to different poles: he to politics, she to evangelicalism. After 11 years together, they separated in 1955.

Soon after, he met Winnie Madikizela after catching a glimpse of her through a car window. Though Winnie, the city’s first black social worker, would later become a tremendous liability, she was his great love. “The moment I first glimpsed Winnie,” he later wrote in his autobiography, “I knew I wanted to have her as my wife.” Long after she’d driven off, Mandela stood in the rain, watching as the car was swallowed by the city. Winnie knew, however, she’d chosen a revolutionary, and would always come second to the cause. As if to reinforce the point, security police attended their 1958 wedding. “Politicians,” she would say, years later, “are not lovers.”

Politics in South Africa had, by then, taken a sinister turn. The National Party, the main vehicle for Afrikaner nationalism, was gathering strength by focusing on the so-called “Native problem.” Ahead of the country’s elections in 1948, the Nationalists, amid warnings of the “black peril,” put forward a plan it believed would be a “permanent solution” to an increasingly integrated black South Africa: apartheid, literally, “apartness,” a doctrine of racial oppression that called for the complete separation of races.

“Bantustans,” independent homelands, would be carved out of the old reserves. Black South Africans would be forcibly relocated. The cities would belong to the European population. “The Nats,” holding up Biblical texts they believed gave their loathsome project a Christian rationale, appealed to white workers and shopkeepers, who feared competition for jobs, and farmers desperate for cheap, black labour.

In 1948, the party was able to eke out a narrow win. Nationalists would go on to hold power for the next 48 years. African militancy spiked as the government tightened its chokehold on the black population. Mandela and the ANC—often joined by the Indian Congress, Communists and women’s groups—spent much of the decade immersed in non-violent protests. None had any affect.

By the 1950s, every imaginable facet of life was dictated by race laws. Signs proclaiming “blanke” (white) and “nie blanke” papered park benches, buses, schools, neighbourhoods and beaches. As international outrage grew, the government continued to insist their policy was simply “misunderstood.” “It could just as easily be described as a policy of good neighbourliness,” said prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd in 1958.

Such Orwellian rationalizations could not explain away the events of March 21, 1960, when thousands of blacks had gathered in the township of Sharpeville, south of Johannesburg, to peacefully protest the laws that restricted the movement of black people. Police opened fire and killed 69 protestors. Most were shot through the back as they fled police gunfire. Some were children. “As the police emerged to clean up the carnage, one officer grew sick at the sight and vomited,” Time reported. Sharpeville would change everything.

Pretoria declared a state of emergency, banning the ANC and its leadership. Thousands were picked up in mass arrests. Mandela left Winnie with their two baby girls, and went underground. Tambo was sent to London, to mobilize opposition to apartheid. He was unable to return for 30 years.

By this time, Mandela was already straining to stay loyal to the ANC’s Gandhian principle of non-violence. Many in the party, including its leader, Chief Albert Luthuli—the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize—refused to abandon the principle, causing bitter divisions. But the slaughter at Sharpeville had convinced Mandela their peaceful rallies were no match for the government’s newfound aggression. And, at 42, Mandela was already the country’s most dynamic political figure. He summoned a British reporter to his hideout, an apartment belonging to Wolfie Kodesh, a young Communist and freedom fighter.

Asked whether there was any likelihood of violence, Mandela replied: “There are many people who feel that it is useless and futile for us to continue talking peace and non-violence against a government whose reply is only savage attacks on an unarmed and defenseless people. And I think the time has come for us to consider, in the light of our experiences, whether the methods which we have applied so far are adequate.”

It was the ANC’s first call to arms. The young politician was off to battle.

In 1961, Mandela was secretly appointed commander-in-chief of the ANC’s newly formed armed wing, uMkonto weSizwe, “Spear of the nation.” He criss-crossed Africa, meeting with heads of state to get funding and combat training.

He was to become more famous from the shadows than he had ever been in broad daylight, noted British writer Anthony Sampson, who first met Mandela when he was editing Drum, the country’s pioneering black magazine. In his 15 short months heading MK, as the organization was known, the legend of Mandela grew. He became public enemy No. 1—dubbed the Black Pimpernel by the press, after the fictional Scarlet Pimpernel, who’d evaded capture again and again, taunting his enemies with every close call. Mandela, dressed in workers’ coveralls, posed as a gardener and chauffeur—which allowed him to travel the country freely. But “he became increasingly bold,” says Fatima Meer, a family friend and anti-apartheid activist. “He took chances. He would have the family visit him over weekends. Winnie would take the children.”

Mandela, by then, was famous. His photos, in which he wore a beard, were everywhere. But when Sisulu and the others suggested he shave the beard, he refused. He wasn’t without weakness, says Ahmed Kathrada, a fellow anti-apartheid activist with the South African Indian Congress, “one of which is vanity.”

On Aug. 5, 1962, his career as a guerilla commander ended abruptly. He was arrested near Pietermaritzburg, after police were tipped off to his whereabouts. Police were unable to link him to sabotage, and charged him with inciting strikes and leaving South Africa illegally. His first court appearance electrified spectators. “I can never forget this. It was amazing,” says freedom fighter Kodesh. “He came up, this tall, big, athletic man—he had a kaross, (a sheepskin), beads round his neck, beads round his arms. There was a complete hush. Even the policemen went pale to see this huge man in his national costume.” Mandela said he’d chosen traditional dress—which officials repeatedly failed to confiscate—“to emphasize the symbolism that I was a black African walking into a white man’s court.”

Three weeks later, when the prosecution rested after calling 60 witnesses, Mandela surprised the court by announcing he would call no witnesses. Instead, he had prepared an hour-long political speech: “Posterity will pronounce that I was innocent,” he concluded, “and that the criminals that should have been brought before this court are the members of the government.”

After receiving a five-year sentence, Mandela was led away in shackles. Outside, he could hear the slow, moving hymn, Nkosi Sikelel iAfrica (God Bless Africa), by then a symbol of the anti-apartheid movement.

In the summer of 1963, seven months after he was sent to prison, police raided the Lilieslief farm in the Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia, where they found 10 ANC leaders, including Sisulu, Kathrada and Govan Mbeki, and a cache of new evidence related to MK’s activities. Mandela and nine others were charged with sabotage and conspiracy. This time, he faced death by hanging. Asked to enter a plea, Mandela replied: “The government should be in the dock, not me. I plead not guilty.”

“We knew there was no hope of getting an acquittal,” George Bizos, Mandela’s long-time lawyer explained. “The question was: how to approach the trial?” Mandela and his co-defendants agreed to use the dock as a platform and theatre. Mandela’s final address to the court at the Rivonia Trial, as he dedicated himself to the ideal of an equal, democratic South Africa, would become one of the greatest speeches of the century. “It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die,” would be the last words the world would hear from Mandela until his release in 1990. “There was dead silence,” said Denis Goldberg, Mandela’s co-accused. “It somersaulted him and the ANC and the need to end apartheid into the global consciousness.”

The only question remaining was whether Mandela and the others would hang. Mandela had prepared himself for death—not because he was brave, he said, but because he was realistic. Alone in his cell, he ruminated on a line from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure: “Be absolute for death; for either death or life shall be the sweeter.”

In the end, Mandela and his co-accused were convicted, but spared the death penalty, likely due to intense international attention. The non-whites were sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island—Africa’s Alcatraz, where South Africa banished its most hardened and dangerous criminals.

Mandela’s three decades behind bars transformed him: Gone was the combative lawyer and freedom fighter who loved making headlines. In his place emerged a disciplined and reflective nation-builder, a conciliator who sought to find common ground, whatever the cost.

As a political prisoner and a black man, Mandela endured the penal system’s worst conditions—the least food, the fewest privileges. On Robben Island, he slept on a thin mat on a stone floor in his seven-by-nine-foot cell. His lungs and eyesight would be permanently damaged by the 13 years he spent working in the island’s blinding-white limestone quarries, some of them overseen by a guard nicknamed “Thick Neck,” who had a small swastika tattooed to his wrist.

Allowed just one letter and visitor every six months, he ached for his family. “Letters from you and the family are like the arrival of summer rains,” he wrote in a letter to Winnie in 1977—they “liven my life. I become full of love.” He didn’t see his daughter Zindzi from the age of three to 15. Thembi, his firstborn son, who had never forgiven him for sacrificing family for politics, was killed in a car crash while he was on Robben Island. “We had to force ourselves not to give into despair,” Mandela would later write.

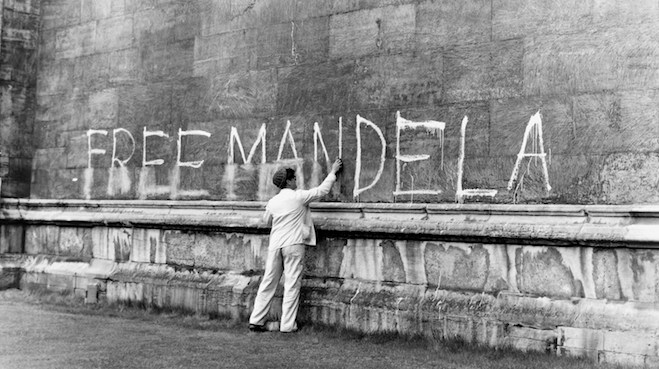

A successful embargo throughout South Africa forbidding any mention of Mandela had, meanwhile, cast doubt on the worth of his sacrifice. “His words, his images were banned,” says Sampson, the British writer. “Mandela’s name was not mentioned at all, even amongst black friends. To all intents and purposes, he had been forgotten.”

The “politicals,” as their warders called them, learned to break the monotony by teaching—history, geography, whatever subject they knew well. Mandela taught politics to the island prison’s young activists, earning it the nickname, “Mandela University.” “It was a tragedy to lose the best days of your life,” Mandela once said. “But you learn a lot.”

Mac Maharaj served 12 years with Mandela on Robben Island and is now South African President Jacob Zuma’s spokesman. “The loneliness of a freedom fighter—Mandela survived it and became more human,” he says. “That’s a very important message to all of us.”

South Africa’s economy, heavily reliant on a migrant, black workforce, had grown enormously since Mandela’s imprisonment; through the 1970s, it saw growth second only to Japan. The Bantu education system focused on producing black workers rather than educating the students, and the country was spending 16 times more on white education per pupil. The decision in 1976 that school be taught half-time in Afrikaans proved to be the breaking point. Students launched a series of protests in Soweto. The authorities reacted with deadly force. On June 16, 29 were killed, most of them children. Protests quickly spread, engulfing the country.

Resistance to white rule grew. In 1985, president P.W. Botha declared a state of emergency, imposing curfews, new censorship laws and granting the army, police and intelligence services virtually unlimited powers. More than 1,000 were killed that year, virtually all blacks.

By then, sanctions and boycotts had begun to bite. International banks were calling in their loans, causing the rand, the country’s currency, to plummet. South Africa was bleeding. Pressure, meanwhile, was mounting to free the prisoner who had become a global icon.

In 1988, having just turned 70, Mandela contracted tuberculosis, and spent days coughing up blood. Botha was terrified Mandela would die in detention: He knew that the international community—by then, openly disgusted with the regime—would never forgive South Africa; and his death would unleash a wave of violence unlike anything the country had yet seen. So the president, a stubborn, brute of a man, offered to free Mandela on condition he renounce violence. “Make it possible,” he explained, “for me to act in a humane way.”

Botha, known as the “Old Crocodile,” believed the move was brilliant: If Mandela refused, surely the West would understand why he couldn’t let him go free. But there was no way Mandela would renounce the ANC’s armed struggle. It was the reason he had spent all those years in a jail cell; it was the banned organization’s lone negotiating card.

Mandela had already issued his response—made after a similar earlier offer—through his then-24-year-old daughter, Zindzi; Winnie and the rest of the family had been barred from speaking publicly. At a Soweto rally celebrating Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Nobel Peace Prize, Zindzi mounted the platform to deliver her father’s first political statement in more than 20 years: “I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom,” it began. “I am not less life-loving than you, but I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free . . . Your freedom and mine cannot be separated,” Zindzi concluded, to thunderous cheers. “I will return.”

But behind closed doors, Mandela and justice minister Kobie Coetsee had begun secret negotiations—even Mandela’s ANC was unaware of them. In July 1989, Mandela was secretly taken to meet Botha. To ensure he looked smart before the president, he was provided with a suit. Seconds before they were to meet, an official noticed Mandela’s shoelaces had come undone, and bent to lace them. It is hard to quantify what Mandela lost over three decades in prison, but the anecdote helps illustrate just that. Prisoners were forbidden shoelaces; Mandela had been jailed so long, he’d forgotten how to tie them.

That initial meeting with Mandela would also be Botha’s last while in power: One month later, the president was removed from office by his National Party after he suffered a stroke.

On the surface, F.W. de Klerk, Botha’s arch-conservative replacement, seemed an unlikely candidate to do away with apartheid. His father Jan, a Senate leader, had been one of apartheid’s original architects. But the new president was under intense pressure, both at home and abroad, to bring change. The economic crisis was becoming acute. “We were teetering on the edge of the abyss,” de Klerk would later tell his brother.

De Klerk insists he underwent no transformation. At his core, he is a clear-sighted pragmatist, not an ideologue; he says he simply recognized that apartheid had to change “fundamentally.” De Klerk remained firmly opposed to majority rule, envisaging a power-sharing agreement with the country’s black population: “Don’t expect me to negotiate myself out of power,” he told one Western diplomat. Yet de Klerk, in the end, would do precisely that.

His first radical step came on Oct. 15, 1989, when he freed Sisulu, Kathrada and four other political prisoners after 25 years’ imprisonment. Mandela had negotiated their release while at Victor Verster prison, east of Cape Town, where he was now being held: “He was like the captain of a ship,” Coetsee, the justice minister, recalls. “He wanted to see them safely outside before he himself left.”

Then, in a remarkable speech to Parliament on Feb. 2, 1990—the contents of which de Klerk kept so secret, he didn’t even tell his wife beforehand—the president calmly announced he was freeing Mandela, lifting the ban on ANC and negotiating a new constitution for South Africa. No one had anticipated such bold reforms. “The time has come for us to break out of the cycle of violence and break through to peace and reconciliation,” said de Klerk. “The time for negotiations has come.” Nine days later, Mandela walked free.

The government wanted Mandela to hold a joint press conference with de Klerk, but Mandela refused. The small stand would set the tone for the negotiations that followed. The balance of power had suddenly shifted. The government no longer controlled Mandela. The upper hand was his.

Mandela was driven to the gates of Victor Verster. Along the way, the families of his warders stood in the gardens of staff cottages, waving him off. Within sight of the gates, Mandela stepped out, in a grey suit and dark tie, walking slowly, hand in hand with Winnie, taking his first steps of freedom at his own pace.

The size of the crowd, with hundreds of TV cameras and reporters and several thousand well-wishers, astonished him. He was amazed so many white people had come—some, he would later recall, “even raised their clenched fists in the ANC power salute.” On the road to Cape Town, which was lined with well-wishers, he stopped his motorcade to tell a white family with two young children how inspired he was by their support.

Remarkably, no one in the crowd knew what Mandela looked like. No photo of him had been published since 1964. And so, for some, the day’s joy was tinged with sadness. After 27 years in prison, gone was the strong, broad-shouldered, young lawyer. “His face, once round and full-cheeked, had narrowed,” his friend, the apartheid activist Hilda Bernstein, would later say. Mandela’s hair was mostly white. His back was stooped. He had never seen a microwave or celebrated Valentine’s Day. Mandela, however, felt nothing but joy: “I felt—even at the age of 71—that my life was beginning anew,” he later wrote in his autobiography. And, in June 1990, the ANC suspended the armed struggle.

Mandela’s long march wasn’t over yet. The day he was freed, white racists marched on Pretoria shouting: “Hang Mandela!” Violence, far from ending with his release, was actually on the rise. It emerged that police, with de Klerk’s knowledge, were secretly funding the Inkatha Freedom Party, the ANC’s Zulu rival, in hopes of derailing the transition to democracy. Mandela would never regain his trust in de Klerk. Negotiations stalled, and their relationship grew rocky.

“It was a very tense period,” says Helen Zille, the president of South Africa’s Western Cape province, and a former apartheid activist. The townships were like war zones, as Inkatha fighters took on ANC supporters. But the real threat, as Mandela saw it, was the support the far-right commanded within the security forces, army and police. “No one knew where this was going,” says Zille. “The inevitable logic was civil war—a clash of nationalisms.”

Mandela’s personal life was equally stormy. Winnie, once the rebellion’s courageous and beloved matriarch, had become a scandalous, complicated figure. She’d surrounded herself with a group of young thugs called the Mandela United Football Club, and stood trial for her role in the 1988 kidnapping and subsequent murder of 14-year-old activist, Stompie Seipei, whom Winnie had accused of being an impimpi, a police informant. Publicly, Mandela stood by through her 1991 trial, which found her guilty of being an accessory to Seipei’s kidnapping and assault. (On appeal, her six-year prison sentence was reduced to a $10,000 fine.) But her criminality and blatant infidelity proved too much for Mandela and, soon after, he announced their separation. In 1993, Oliver Tambo, one of his closest friends, died suddenly after suffering a stroke. Mandela said he felt like the loneliest man in the world.

Meanwhile, his relentless pace was taking a toll. He’d kept the austere routine of prison life: He was up at 5 a.m. to exercise and at his desk by 7. He was travelling the world, meeting with heads of states and dignitaries, pleading with them to keep sanctions in place, to keep pressure on the South African government to push forward with democratic reforms. It was as though he were trying to make up for lost time, and he began suffering occasional bouts of exhaustion.

On April 10, 1993, Chris Hani, the most popular ANC leader after Mandela, was assassinated, a hit commissioned by members of the right-wing Conservative party. Hani had a near-cult following, and his murder seemed certain to spark a blaze of violence.

Mandela flew immediately to Johannesburg. In a nationally televised address, he appealed to his followers to remain calm and forego reprisals—“acts that serve only the interests of the assassins.” Yes, a white man had killed Hani, Mandela acknowledged. “But a white woman had risked her life so that we may know and bring justice to the assassin.” Mandela’s supporters heeded the call, though the emotional response was unlike anything South Africa had seen.

De Klerk, by contrast, stayed silent, and chose to remain in his Cape holiday home. It was Mandela, not the president, who had taken control of the crisis, halted the bloodbath and who now, it seemed, commanded the nation. By inviting the leaders of the far-right into his home for frank negotiations, Mandela convinced them to put down their arms. “If you want to go to war, I must be honest and admit that we cannot stand up to you on the battlefield,” Mandela told Gen. Constand Viljoen, leader of the Afrikaner right-wing organization Volksfront, with whom he had developed a warm relationship. “But you cannot win because of our numbers, and you cannot kill us all.”

Mandela was furious with de Klerk, and demanded an election date. Mandela was not always benign, his biographer, Martin Meredith has noted. His face “sometimes settles into an inscrutable sphinx-like stare, the lines and furrows on it marking his displeasure.” He could be “feared as well as revered.” Ultimately, de Klerk crumbled. The election would be held almost one year to the date of Hani’s murder.

Mandela voted for the first time on April 27, 1994. On a cool, sunny day two weeks later, he was inaugurated as South Africa’s first democratic president. The massive event, held on the gentle slopes outside Pretoria’s Union Buildings, brought together even old foes: Bill Clinton and Fidel Castro, Yasser Arafat and Israeli president Chaim Herzog. More than one billion watched live on TV. Mandela personally invited three of his former prison guards. “Wat is verby, is verby,” he began, in Afrikaans. “What is past, is past.”

His closing words, delivered slowly, methodically, thundered across the veld: “We enter into a covenant that we shall build a society in which all South Africans, black and white, will be able to walk tall without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.” Four thousand guests spontaneously rose in an ovation, as Mandela declared: “Never, never, never again shall it be that this beautiful land will experience the oppression of one by another, and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world.”

The hauntingly beautiful anthem, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, followed. But its final chords were drowned out by the growing roar of six fighter jets rounding Pretoria’s Muckleneuk Ridge. The jets, the same ones that had been hunting Mandela’s fighters in Angola and Mozambique just a few years earlier, buzzed the crowd, each releasing a smoke streamer, forming the six colours of the new flag. “You looked up, you knew the pilots were white,” anti-apartheid activist Kathrada recalls. “But at that point, you knew: They are ours. The great concrete wall of apartheid was broken,” he said. “We destroyed it.”

Mandela never once expressed bitterness about the decades wasted behind bars, nor toward South Africa’s white community. “I was nervous to meet him, being a white Afrikaner and not knowing what to expect from someone we considered to be the enemy,” says Zelda la Grange, who was hired to work as a typist for Mandela as president. But, she says, “he spoke to me in my language, the language of the former oppressor, and disarmed me immediately.”

“There is no point in bringing people together who agree,” Mandela once told the writer Achmat Dangor. “You have to bring together the people who are fighting with each other, who are making it difficult for the country to progress.” So Mandela kept on white presidential bodyguards. When asked to name his hero, he said it was Kobie Coetsee, the former justice minister, who had agreed to negotiate with him at a time when enmity against the ANC was at its peak.

In 1995, a year after Mandela took power, South Africa hosted the Rugby World Cup. The game had long been seen as a Boer sport; but Mandela went out of his way to back a home team—“our boys,” as he called them—that included just one black player. The Springboks won the tournament, but the true triumph was when Mandela donned the team’s forest-green jersey, once a repellent symbol of white racism. He shook the hand of François Pienaar, the Afrikaner captain. “We did not have 63,000 fans behind us today,” said Pienaar, “we had 43 million South Africans.”

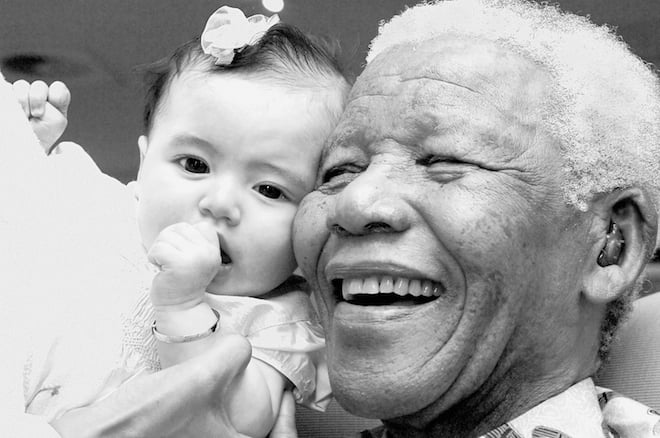

As president, Mandela oversaw a rewriting of the constitution and the creation of a constitutional court whose first act was to abolish the death penalty. He asked Archbishop Desmond Tutu to head the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, South Africa’s bold experiment in atonement. Amnesty was its centrepiece, guaranteed to those whose crimes were politically motivated, and who confessed all they knew. Internationally, he reached out to a world that had spurned South Africa, and his crinkly-eyed smile and high-collared, colourful shirts were more recognizable than Bono’s sunglasses.

Things had turned around in his personal life, too. One spring day in 1996, Mandela made public his love for Graça Machel, walking hand-in-hand with her in his quiet, suburban Johannesburg neighbourhood. “It is wonderful we have found each other after so much pain,” Machel, the widow of Mozambican independence leader, Samora Machel, would later say. They would marry on Mandela’s 80th birthday.

Back in Qunu, Mandela’s hometown, life has changed dramatically. On a visit earlier this year, Mandela’s eldest grandson, Mandla, who is the chief, sat among Mvezo elders, many of them Madibas, Mandela’s clan, to discuss job creation. (He had not yet become the focus of a controversy over moving the Mandela family remains.) Bread, tea and Coca-Cola in 1.75-litre glass bottles were being served, along with barbecued lamb, beans, rice and homemade beer in tin buckets. At the end of the four-hour meeting, bottles of $100 whisky and a live sheep were exchanged as gifts.

Mandla, who stands over six feet tall, has his grandfather’s height, but a soft face and middle. He wears a blue collared shirt, with his jeans rolled below his knees, and carries an iPhone by his side. Mandla remembers visiting Johannesburg as a child and hearing protesters shout “Viva Mandela!”

“I ran home—‘Dad, I am popular out there,’ ” he recalls saying. “My father saw this young idiot who didn’t understand what was happening.” The gravity of being a Mandela would soon hit Mandla, who spent the majority of his childhood in Swaziland for fear of attack. At one point, when Mandela was out of jail, Mandla told his grandfather he wanted to become a DJ. “Nonsense, man. No Mandela can be a DJ,” he said, telling Mandla to study. “When my grandfather humbles himself to you, you must do as he says.”

Despite that legendary persuasiveness and resolve, Mandela, who stepped down in 1999 after a single term as president, couldn’t solve all of South Africa’s problems. And in his absence, the ANC, hobbled by a culture of cronyism and incompetence, has become a sorry spectacle. Too many in government, Tutu has said, are focused on self-enrichment. Rampant inequality remains, and unemployment hovers at around 25 per cent. Mandela’s rainbow nation has lost its lustre.

But judging Mandela by the party and state he leaves behind is hardly a fair or accurate measure. The world doesn’t celebrate Mandela for his four years in the president’s office. He will forever be remembered for his magnanimity, his integrity and his unbreakable strength as he walked the long, tumultuous road to lift South Africa from the darkness of apartheid, and into a new future, whose story isn’t yet 20 years old.

Mandela, however, preferred a simpler appraisal of his life and career: “I was not a messiah,” he said, “but an ordinary man who had become a leader because of extraordinary circumstances.”