Give us more politicians like John Crosbie, please

Stephen Maher: He was unafraid to say things, to mix it up, to tell people to kiss his arse if called for. Politicians today could learn from him.

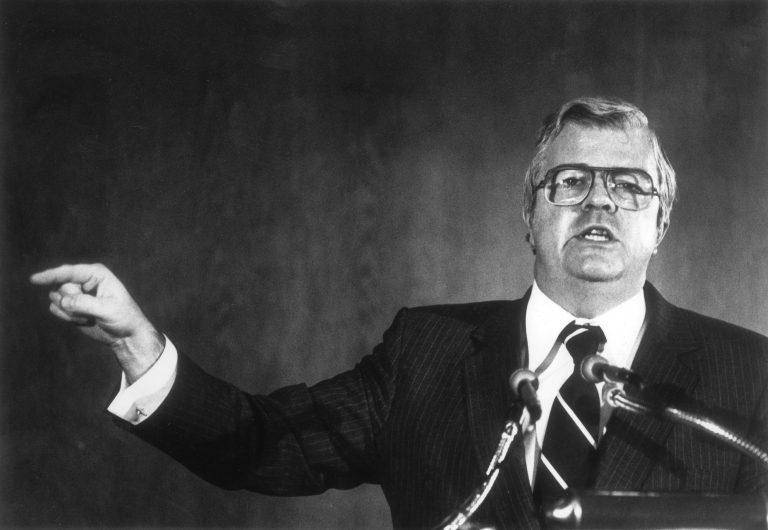

Crosbie on Dec. 20, 1979, when he was federal finance minister (Tibor Kolley / The Globe and Mail)

Share

When I was a young fellow, fresh out of university, I couldn’t find a job in the newspaper business in Halifax, which has always had more would-be journalists than jobs for them, so I moved to Grand Falls, Nfld., and got a job with the Advertiser, the beginning of a grand three-year adventure in that province.

At that time, John Crosbie was the minister of fisheries and regional chieftain in the then terribly unpopular government of Brian Mulroney.

I watched as Crosbie presided over the worst ecological catastrophe in Canadian history, the destruction of the northern cod stocks, and listened to Newfoundlanders say his name like a curse.

You won’t find anyone to curse him now, but it was a terrible time.

For centuries, Newfoundland cod nourished millions of people around the world, and provided Atlantic fishing communities with their livelihood. That would still be the case except that the big fishing companies got better and better at finding the fish and the scientists were slow to adjust their models to reflect that awesome industrial efficiency until it was too late.

When the scientists realized that the stocks were collapsing, they told Crosbie, but he shrank from the horrible news and dragged his feet until 1992, when he finally declared a moratorium, sparing the last of the species.

READ MORE: A disastrous tsunami’s lethal legacy in Newfoundland

On Canada Day in 1992, in the beautiful fishing community of Bay Bulls, not far from St. John’s, Crosbie was confronted by hundreds of angry, fearful fishermen and plant workers, who blamed him, with some justice, for his role in destroying the fishery that had fed their families for so long.

Crosbie, fresh from fighting in Ottawa for a decent compensation package for the people yelling at him, lost his patience.

“I didn’t take the fish from the goddamn water, so don’t go abusing me,” he shouted back.

I was there the next day, at the Hotel Newfoundland, when he made the official announcement of the moratorium, with a dozen police to protect him. When angry fishermen yelled and banged on the doors, demanding to be let in, I was rattled but he didn’t seem to be.

Crosbie waited too long to end the fishery, as most politicians would have, but at least he had the courage to face his people when he had no choice but to shut down the most important industry in the province, throwing 40,000 people out of work.

It was an admirable personal quality. Crosbie didn’t shrink from questions, didn’t insulate himself from the people he was sent to Ottawa to serve, an example many politicians from the next generation—like Caroline Mulroney, for instance—would be wise to contemplate.

Don’t hide from the people. Let them have their say. Be ready to face the goddamn music or take up another line of work.

Crosbie’s personal accessibility was a kind of accountability.

It is not a surprising quality to find in a Newfoundlander. There is something about the place—rooted in the harsh realities of fishing life, I believe—that makes it hard to put on airs. Just as Newfoundlanders will open their homes to strangers without thinking twice, they will not put up with those who think they are better than their neighbours.

Crosbie, although he came from what passes for a local aristocracy—and had an intellect to rival anyone in politics—never acted as though he was too precious to deal with fishermen, plant workers or an ill-informed reporter from the local weekly paper.

Crosbie’s other great quality, which is also characteristic of Newfoundland, was his wit.

He threw away more good lines than most politicians have in their careers. In a scrum, a speech, an interview, or in debate in the House of Commons, he was always droll, and often actually really funny, rolling out real jokes, not the canned icebreakers that most politicians deliver before they settle in to bore us to death.

There’s something funny about Newfoundlanders, especially Townies, who seem to pass their days in the fog-shrouded streets of St. John’s thinking up humorous things to say to whomever they bump into next. It can’t be an accident that most of our best comedians are Newfoundlanders.

I have two favourite Crosbie jokes.

The first comes from 1987, when Newfoundland Liberal MP George Baker, himself quite a wit, stood up in question period to ask why Air Canada and Via Rail were serving potatoes imported from Belgium while Canadian farmers were forced by bad markets to plow their spuds under.

“Mr. Speaker,” said Crosbie. “Surely a baker would be concerned about a potato.”

Baker replied that soon Crosbie would be known as “Mr. Potatohead, and perhaps Bud the Belgian Spud,” and encouraged him to acknowledge that Canadian potatoes were the best in the world.

“Mr. Speaker,” Crosbie replied. “The honourable gentleman is a real pomme-de-terrorist, if not a mashochist.”

He then promised, properly, to ask the department to source potatoes from Canada, if possible. “If they can find them the size of the honourable member’s head, I’m sure they will be more than willing.”

In my many years sitting in the gallery, I never witnessed an exchange as droll.

The other story I like is from after Crosbie left federal politics, when CBC Radio’s Vicki Gabereau had a live show in Newfoundland. She challenged Crosbie to taste two pieces of smoked salmon and try to identify which one was from the West Coast and which was from the East Coast.

When Crosbie gave his answer, Gabereau asked him if he preferred its flavour. “If I’m correct I do,” he said, ever the politician.

Crosbie’s wit sometimes got him in trouble.

Sheila Copps forgave him, but it was actually politically incorrect for him to joke, as he once did, that she should “pour me another tequila, Sheila, and lay down and love me again,” quoting a long forgotten country tune, sexualizing a young female politician in a way that he later acknowledged was inappropriate.

And he might have won the federal Conservative leadership in 1983 if he hadn’t lost patience with reporters badgering him about his bad French and snapped: “I cannot talk to the Chinese people in their own language either.”

But give us more politicians like him, please. He was smart as a whip, an energetic and capable champion for Newfoundland and Labrador, and blessedly colourful, unafraid to say things, to mix it up, to tell people to kiss his arse if the occasion called for it.

Our politicians now have scripts for everything, and pride themselves on their ability to stay in the message box, repeating their talking points no matter what anyone asks them.

You can’t really blame them, given the social media flash mobs that delight in castigating the politically incorrect, but it makes our public life awfully bland.

Crosbie was proud to have spoken as he did. “Thinking of my own career, I was not politically correct, but I certainly feel I did the best I could and I was as straight and honest as it’s possible to be in politics today,” he said of his career in retirement.

Today I keep thinking of the line from Hamlet: “He was a man. Take him for all in all. I shall not look upon his like again.”