How to ignore the NDP’s new talking points

Our man in Alberta on the NDP’s Edmonton sojourn, and misreporting of its ‘federal minimum wage’

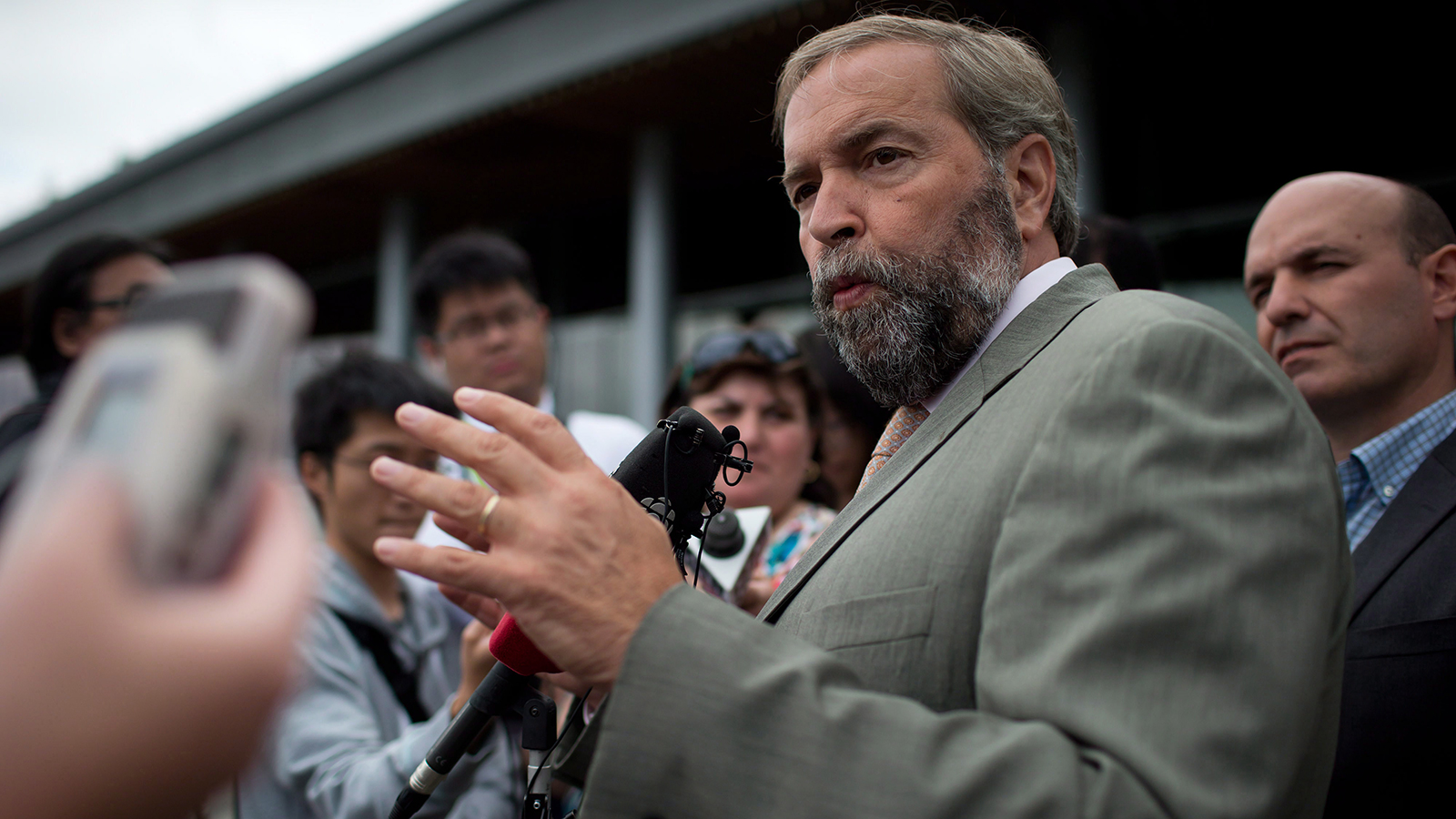

New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair (C) receives a standing ovation from his caucus during Question Period in the House of Commons on Parliament Hill in Ottawa November 25, 2013. REUTERS/Chris Wattie (CANADA – Tags: POLITICS) – RTX15T0R

Share

When the Liberals held their national summer caucus retreat in Edmonton in August, a lot of people wondered what they were thinking. So, too, this month, when the New Democrats did the same thing, congregating in the city’s Hotel Macdonald. Of course, the NDP has at least one obvious answer to “Why Edmonton?” that the Liberals didn’t: They hold a seat in Alberta, Linda Duncan’s Edmonton-Strathcona.

One of the key talking points of the NDP summit was: “Only New Democrats beat Conservatives in Alberta.” That might get an argument from Anne McLellan and, in any case, Duncan has won Strathcona twice, mostly because local Liberals rallied behind her and ran perfunctory Liberal campaigns. This won’t happen a third time in the Era of Justin, so one good reason for the NDP to come to Alberta’s capital is to defend Duncan’s beachhead.

But the NDP also has justified hopes in a couple of north Edmonton ridings, notably, Edmonton-Griesbach, which overlaps with three of the four constituencies held provincially by the party. This is already NDP territory: The NDP candidate, provincial education bureaucrat Janis Irwin, just needs to kick the convert.

The contrasting strengths of the opposition parties were highlighted by their back-to-back appearances in Edmonton. The Liberal caucus was small, and contained no Albertans, but was full of familiar, approachable figures. Even a civilian on the Edmonton street would know Marc Garneau or Stéphane Dion. The NDP managed an outstanding turnout in Edmonton, convincing an estimated 93 of the caucus’s 97 members to brave terrible September weather. But even local NDP enthusiasts might have trouble identifying more than a few dozen of the Orange Corps, and, where the mood of the Liberal event was ebullient and relaxed, the New Democrats seemed serious and determined.

At Justin Trudeau’s press conferences in Edmonton, one had the feeling of watching a bullfighter in the corrida. Reporters were consciously trying, without success, to winkle an awkward answer out of him. There is little of that sort of nonsense with Thomas Mulcair. Like all NDP leaders, Mulcair has mastered the details of the long record of Liberal and Conservative perfidy, much the way a bard memorizes an epic poem. Trudeau is new to the highest level of Canadian politics and is something new within it: That is exciting, even to very cynical journalists. It is less often observed that Mulcair, aside from being a New Democrat, is exactly the kind of personality Canadians normally favour for a prime minister.

The Liberals talked grandly of their “Road to 170” seats, the number needed for a majority in the redistributed House of Commons. The NDP, by contrast, kept expectations in check. But Mulcair, aided by a craft beer tasting, was able to fill the theatre of the new Boyle Street Community Centre with about 300 supporters on a cold night. Even given that close to 100 of these were his MPs, it was impressive.

During the hat-passing phase of the party, the compère at the microphone made a pointed joke about how good hair is not a qualification to be prime minister. This was a hint that the party was about to start going negative on Trudeau, which senior members duly began to do the next day. Some will regard this as a lamentable abandonment of standards, but the other new strategic wrinkle was much worse in that regard: the announcement of a policy for a restored “federal minimum wage.”

Provinces set minimum wages for most employees under the Constitution, but Ottawa has an unused right to set a national minimum in private industries regulated under Part III of the Canada Labour Code. The major categories are banking, interprovincial and international transport, and broadcasting. You may be wondering how many people in these technically complicated lines of business are actually making the minimum wage. In the most recent survey of the federal labour jurisdiction (taken in 2008), the answer arrived at by Statistics Canada was: 416 people. In the entire country.

The New Democrats were pretty clearly counting on the press to foul up the story, and it obliged. Some Postmedia newspapers, for example, wrote headlines implying that the new wage floor was for “federal workers.” Economists, who mostly dislike minimum wages anyway, will probably tear into the NDP for a misleading measure that, to a close approximation, helps nobody. And it probably won’t matter much, as New Democrats go on repeating the words “federal minimum wage” for a year.