What we’re not talking about in the assisted-dying debate

Why suicide researchers have a potentially important perspective on the debate over assisted dying

June 20, 2016 – 160620 – James Bolton, MD, Medical Director at the Crisis Response Centre of Winnipeg Regional Health Authority is photographed at his office in Winnipeg June 20, 2016. Dr. Bolton was photographed for a story in the upcoming issue about the potential relationship between legalizing assisted death and shifting public attitudes toward suicide.

John Woods / Maclean’s

Share

James Bolton knows he and his colleagues who work in suicide prevention don’t have to sell the importance of their work. To him, suicide is a temporary state of darkness that permanently steals away youth and years; it sends shock waves through families and friends who may never regain their footing; it is a public health tragedy that must be contained—but never quite seems to be. Bolton has a foot in both the clinical and research worlds, seeing patients and working as medical director of the Crisis Response Centre in Winnipeg while also researching suicide epidemiology (the patterns and causes of its movement through populations).

So it has been profoundly disorienting for him to suddenly see—and it feels sudden, given that until 1972, suicide was a crime in Canada—a conversation about access to doctor-assisted death playing out across the country. “We research ways of trying to discover why the mind goes toward suicide, and how we can prevent that. So we’ve always been thinking about it that way,” Bolton says. “And now, things have totally shifted. Because of my background, I thought, ‘Oh boy, this is totally in opposition to everything that I’ve done.’ ”

But as he thought about it more, he decided he wanted to be involved. He doesn’t think he could support an assisted-death request from a patient whose primary diagnosis was mental illness, but he understands the need for it in cases of irremediable physical illness. And he has joined the working group shaping the implementation of physician-assisted death—which the Senate passed into law on June 17—in Manitoba. “It is delicate,” he says. “But I think suicide researchers can bring quite an important perspective.”

Within Bolton’s research specialty of epidemiology, one of the well-established phenomena is social contagion: the tendency of suicidal behaviour to spike following a death that grabs a lot of attention, whether that’s in a grieving high school or a society transfixed by the loss of a celebrity. Across Canada, assisted death has been front-page news and the subject of dinner-table debate for months. The conversation has revolved around notions of dignity, personal autonomy and the avoidance of unnecessary suffering. In the House of Commons the day before Bill C-14 passed, Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould directly addressed concerns about shifting attitudes toward suicide. “The bill achieves the most appropriate balance between individuals’ autonomy in deciding how their death will occur and protection of vulnerable individuals, as well as broader societal interests,” she said. “These interests include suicide prevention, equal valuation of every person’s life and preventing the normalization of death in response to suffering.”

There is virtually no research on whether there is any relationship between legalized assisted death and suicide rates. Bolton is cautious given that fact, but he hypothesizes that a similar mechanism to social contagion could underlie the debate around assisted death. “That’s what I would suspect: now that that option is on the table and now that it’s discussed at a broader level, there will be some people who will have thought about it and considered it who now decide to act on it,” he says. “It’s an area where we need to be thoughtful with every step we do in terms of discussions at the broad social level.”

A raft of research traces how social contagion of suicide plays out. A 2013 study that looked at Canadian youth aged 12 to 17 over a two-year period concluded that the suicide of a schoolmate or someone they knew personally was linked with their own suicidal thoughts or attempts. (By the time they were 16 and 17, 24 per cent of teens said a schoolmate had committed suicide, and 20 per cent personally knew someone who had done so.) A schoolmate’s suicide had a stronger effect than someone the teens knew personally; the researchers speculate that the death of a peer resonates more than that of an adult, even if they didn’t know the schoolmate personally.

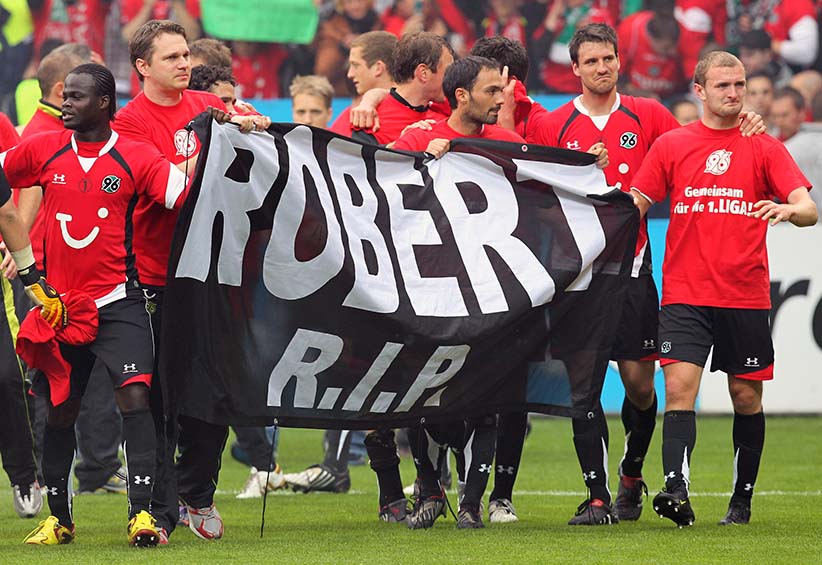

In 2009, a 32-year-old German soccer goalkeeper named Robert Enke jumped in front of a train, sparking a public outpouring of shock and grief. A study published two years later found that railway suicides in Germany spiked by 117 per cent in the 28 days following Enke’s death. And in 1998, after a woman in Hong Kong killed herself by burning barbecue charcoal in an enclosed space, there was a flurry of intense news coverage and subsequent copycat suicides. The authors of a 2013 study estimated that each news story on a suicide by charcoal burning was associated with a 16 per cent increase in suicides by the same method the following day.

Social contagion is so accepted that many jurisdictions and media organizations have guidelines for coverage of suicide, and journalists often tread lightly. One of the World Health Organization’s recommendations nearly echoes the justice minister’s recent words: “Avoid language which sensationalizes or normalizes suicide, or presents it as a solution to problems.”

In suicide-prevention research, social contagion is a wholly negative effect that can potentially spread destruction through mere communication, Bolton points out—but with the public debate around assisted death, that paradigm could be flipped on its head: patients who may benefit from that intervention are getting more information and control. Bolton offers a rueful, half-formed chuckle as he contemplates how complicated this is. “As hard as that can be from a medical standpoint, maybe it’s a conversation we need to be having,” he says.

Annette Hanson, an assistant professor of psychiatry with dual appointments at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, has been an outspoken critic of assisted death in Maryland; the state’s latest attempt at a law fell apart in March. She is particularly perturbed by the argument that one of the reasons people seek assisted death is to avoid placing a hardship on loved ones. “Someone with clinical depression feels like a burden on everyone,” she says. “And this conversation reinforces the idea that maybe they really should relieve that burden.” Hanson rejects the notion that assisted death is fundamentally distinct from suicide—an argument often based on the assertion that assisted-death patients would very much prefer to continue living, were it not for a devastating illness. “Someone with a mental illness who kills themselves would certainly prefer to live without their illness if they had the choice,” she says.

Richard A. Posner, a judge and senior lecturer at the University of Chicago’s law school, has argued that “when limited to cases of physical incapacity, [assisted death] may actually reduce the number of suicides and postpone the ones that occur.” His reasoning is that some people diagnosed with serious illnesses, who may otherwise attempt to take their own lives, will not do so if they know they can safely and reliably obtain a doctor’s help later. Similarly, Exit, a right-to-die group in Switzerland, asserts that its “option of physician-assisted suicide is actually an effective form of suicide prevention. Living in the certain knowledge of a way out has motivated more than half of the people originally intent on dying to keep enduring their painful lot until they passed away the natural way.”

The lone study that has so far examined the relationship between assisted death and suicide rates does not align with these views. Published in the Southern Medical Journal in 2015, it examined how doctor-assisted deaths and unassisted suicides in Oregon, Washington and Montana tracked with the legalization of assisted death in those states. Lead author David A. Jones is director of the Anscombe Bioethics Centre (a Roman Catholic academic institution) at Oxford University. The study controlled for known suicide influences, and concluded that rates did not decline following the advent of assisted death. There were some indications that they in fact went up “significantly,” Jones says, but as they added more controls to the data, the effect dwindled. That essentially means it’s impossible to say those effects weren’t due to something else that makes Oregon, for instance, different from Ohio. Jones is opposed to assisted death, in part because of the inherent tension between its availability and suicide messaging. “There’s an intuitive difficulty in trying to put forward a suicide-prevention policy in which you say, ‘Every suicide is a tragedy,’ and at the same time a strategy in which you say some assistance with taking your own life—even with people who are not terminal—is quite reasonable, because if I were in their state, I might be miserable too,” he says.

James Downar, a critical care and palliative care doctor in Toronto and member of the physicians advisory council of Dying with Dignity Canada, dismisses the premise and methodology of Jones’s study as “very simplistic logic.” And beyond that, what he sees in the data are pronounced swings in suicide rates that do not neatly correlate to the legalization of assisted death.

Downar maintains that the major drivers of suicide—poverty, substance abuse, mental illness—are completely distinct from those driving demand for assisted death, and those risk factors need to be the focus of prevention efforts.

He concedes that the debate over assisted death could lead to greater social acceptability of suicide. “But to some degree, what I’m asking is: is the effect significant enough that you want to limit people’s human rights?”

More fundamentally, he rejects that the two topics should be part of the same conversation.

“Comparing physician-assisted suicide to suicide is like comparing a stabbing to cardiac surgery,” he says. “The only thing in common is the knife.”