The art of the climate change deal

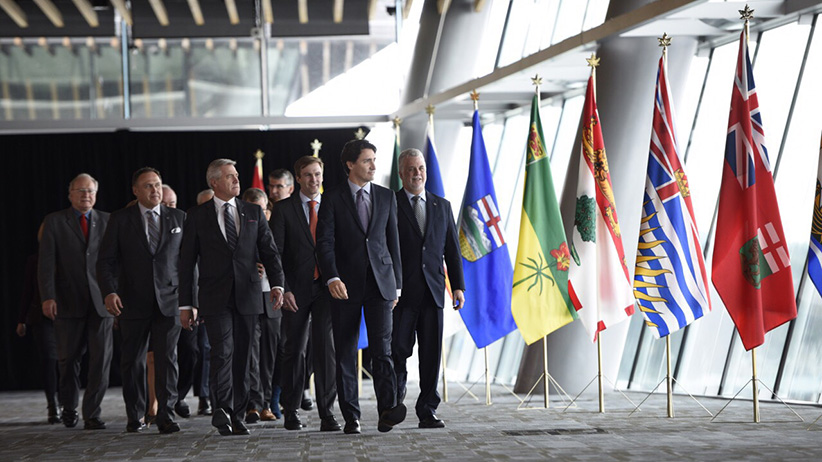

At their Vancouver meeting Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the premiers put off a clear decision on the hardest part of a national climate change plan.

(Photograph by Jimmy Jeong)

Share

Midway through Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s behind-closed-doors session with the premiers today, the TV sets outside their meeting at the Vancouver Convention Centre showed Donald Trump on the news channels putting on his crazy show. And here, as just about everywhere on the planet, the leading bidder for the U.S. Republican presidential nomination was mostly a weird, unsettling distraction.

Still, he did manage to plug his book a couple of times, Trump: The Art of the Deal, and the title, at least, did sort of resonate. Trudeau has proven himself to be an artful politician, that’s for sure, but this encounter with the premiers was the first time he was seriously tested when it came to deal-making. The particular deal he needed out of today’s talks on combatting climate change was a declaration from the premiers that acknowledged the wisdom of pan-Canadian carbon pricing.

It’s been Trudeau’s goal going back at least to a speech he gave last winter at Calgary’s Petroleum Club, where he asserted that many oil and gas execs already know pricing carbon—the best way to send a signal that drives down consumption of fossil fuels—is a good thing that Canada needs. Trudeau’s winning platform in last fall’s election elaborated: “We will work together to establish national emissions-reduction targets, and ensure that the provinces and territories have targeted federal funding and the flexibility to design their own policies to meet these commitments, including their own carbon pricing policies.”

Today was supposed to be a big day on the road to fulfilling that pledge. But the language in the declaration the antsy premiers were willing to sign onto was more art than deal. Does it bind the provinces to carbon pricing? There’s some verbiage to hack through. “We will identify measures that governments can take to grow their economies and reduce emissions in the long term,” reads a key section. “To this end, we directed immediate work in four areas: clean technology, innovation, and jobs; carbon pricing mechanisms adapted to each province’s and territory’s specific circumstances and in particular the realities of Canada’s Indigenous people and Arctic and sub-Arctic regions; specific mitigation opportunities; and adaption and climate resilience.”

Speaking to reporters after the meeting, Trudeau was asked in various ways to interpret the declaration’s wording on carbon pricing. Does it amount to an agreement that every province must impose a price? “Putting a price on carbon, carbon pricing, is an important part of the suite of tools that we will have to bring forward the low-carbon economy that we need,” he said for starters.

But could a province get out of pricing carbon—usually understood to mean a carbon tax like B.C.’s, or a cap-and-trade system like Quebec’s—by instead adopting, say, energy efficiency regulations? “We have established working groups to dig into these and other questions,” Trudeau said, “to ensure that the mechanisms that we put in place will reach our goals of reducing carbon emissions in significant ways…”

So, if the allowed mechanisms for pricing carbon remain to be spelled out, what about the price itself? Trudeau was asked if a minimum price must be applied in every province. “These are discussions that we will be engaging in when the working groups convene over the next six months, to look at the best way to reduce emissions,” he said, adding again in a bit, “And carbon pricing is an important part of the suite of tools that we will be using.”

That suite of tools, according to some premiers, is surprisingly varied. For instance, Saskatchewan’s Brad Wall thinks carbon pricing must include his province’s project that captures carbon dioxide from a coal-fired power station, and sells it to oil companies, who pump it into the ground to get more crude. Nova Scotia’s Stephen McNeil argues his province’s investment in hydro has raised electricity prices in what amounts to putting a price on carbon.

With imaginative positions like those on the table at the outset, the working group Trudeau kept mentioning has a tough job ahead narrowing the definition of carbon pricing to something meaningful. If the real reckoning over carbon pricing was avoided today, it can’t be forever. Trudeau has some time, though. Most Canadians want his conciliatory style to work. The confrontational alternative—in its most bizarre form—dominates the news. Against that cautionary contrast, even today’s evasive declaration is likely to strike most voters as just part of the deal they struck when they elected Justin Trudeau last fall.