The Conservatives’ murky position on ‘conscience rights’ in health care

Justin Ling: The Tory platform says the party will protect conscience rights in health care, but won’t say whether that might restrict access to abortion or deny care to trans people

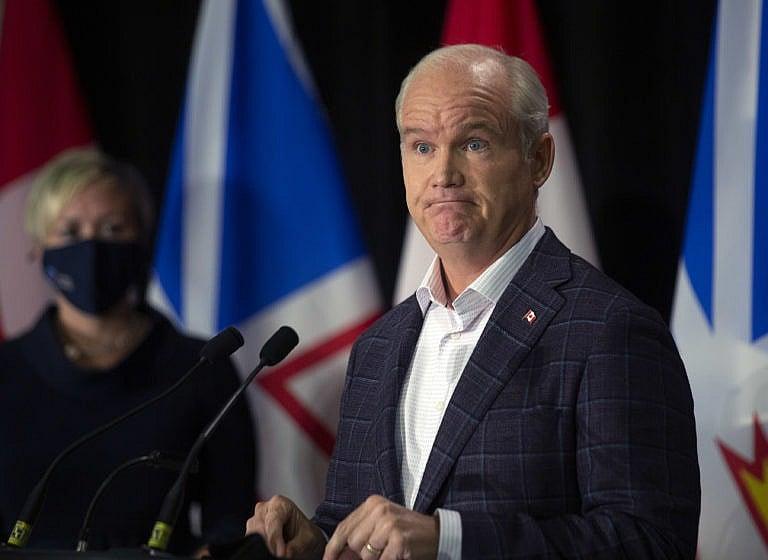

O’Toole takes questions from the media during a press conference in downtown St. John’s, N.L. on July 26, 2021 (Paul Daly/CP)

Share

Erin O’Toole’s Conservatives won’t say whether their plan to extend ‘conscience rights’ to doctors, nurses and health-care providers will permit denying care to LGBTQ people.

O’Toole was hammered on the campaign trail on Thursday over a line in his platform which pledges that his hypothetical future government will “protect the conscience rights of healthcare professionals.”

It’s language that comes directly from a coalition of faith-based organizations which are hoping to protect religious and socially conservative doctors who want to opt-out of providing care they don’t believe in.

But what, exactly, O’Toole’s proposal would look like remains murky. O’Toole was asked directly whether the hypothetical provisions could restrict access to abortion—while he iterated he was pro-choice, he didn’t directly answer the question.

[contextly_sidebar id=”yhav8ODtl8uQTgL3xRcNbwrPf6X9hhIA”]

I reached out to the Conservatives to ask whether this conscience rights pledge would allow doctors to refuse care to LGBTQ people—particularly, trans youth.

A spokesperson for the party responded with a list of times that Liberal MPs mentioned conscience rights in reference to medical assistance in dying. I responded, reiterating my question: Would O’Toole be comfortable protecting doctors who refuse to provide health care to trans kids on the basis of religious objection?

The spokesperson replied again, linking to a tweet again iterating the Liberals’ support for conscience rights specifically relating to medical assistance in dying. A second follow-up asking for clarity went unanswered.

Conscience rights are not necessarily controversial, if they are applied in a limited way. Many provincial regulatory bodies allow health-care providers to opt out of providing certain services, but require them to refer patients to another provider who can offer the sought-after care. The Trudeau government did enshrine conscience rights into their legislation legalizing medical assistance in dying. The Canadian Medical Association’s guidelines say that physicians may act according to their moral convictions but instructs them to “meet your duty of non-abandonment to the patient by always acknowledging and responding to the patient’s medical concerns and requests whatever your moral commitments may be.”

But enshrining open-ended protections for healthcare providers to deny service into federal law would be a massive shift. There has been a broader push to up-end that status quo, especially from groups like the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada. Those groups have sought to expand those conscience rights to cover things like abortion services and beyond. In Alberta, United Conservative Party backbencher Dan Williams introduced legislation that would allow health-care providers to deny any service or procedure if they believe their “conscientious beliefs would be infringed”—the decision could not be reviewed, nor would the doctor need to refer the patient to another provider. (That bill was abandoned at committee.)

South of the border, Republicans have worked feverishly to enshrine conscience rights into federal law. In 2018, the Trump White House unveiled new rules that would protect the conscience rights of healthcare workers, even opening an office in the department of Health and Human Services to stick up for those objectors. The move was an explicit attempt to limit access to abortion and trans-affirming healthcare.

In 2019, a coalition of organizations—including prominent LGBTQ groups—sued the Trump administration, arguing that the rules stood to discriminate against women and queer people.

In its defence, the Trump administration actually provided 11 examples where conscience rights were supposedly infringed. They ranged from a prison worker objecting to providing hormone therapy for transgender inmates to a pharmacist who objected to filing birth control prescriptions.

The court struck down the Trump administration’s rule, in a major win for the litigants.

In Canada, O’Toole has been an enthusiastic supporter of the LGBTQ community—but not everyone in his party has been on the same page. In recent months, MPs like Tamra Jansen and Jeremy Patzer stood in the House of Commons to defend the abhorrent practise of conversion therapy, and to assert that parents should have authority to overrule trans kids’ access to gender-affirming health care. At final reading, half of O’Toole’s caucus voted against banning conversion therapy.

The Coalition for Conscience and Expression, one of the most vocal groups around conscience rights in health care, also opposed the bill to ban conversion therapy as they feared it could ban “appropriate therapies and forms of support that are intended to address unsafe, underage, harmful, or destructive sexual behaviours,” a concern not shared by any major medical group.

As it stands, health care is regularly denied to trans people in Canada. Research from TransPulse indicates that trans people in Ontario are nearly twice as likely to not have a family doctor and that HIV-positive trans people regularly face denial of services. Another research project found that trans people were three times more likely to lack essential care than the general population.

If Erin O’Toole plans on making it even easier for health-care providers to deny care to trans people, he should come out and say it.