The path to a Tory win: Quebec

Philippe J. Fournier: Are the Conservatives quietly making a breakthrough in Quebec? New polls show a glimpse of progress—and a big challenge.

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer responds to a question during a news conference in Montreal on Jan. 21, 2019 (Paul Chiasson/CP)

Share

The most recent polls that were in the field as Canadians prepared to set their minds on vacation mode showed more of the same basic trends as the last few months: the Liberals have partially recovered from five months of (mostly self-inflicted) negative stories and appear to have stopped the bleeding; the Conservatives remained in first place—both in the polls and in the seat projections; and the Greens are slowly creeping up on the NDP for third place in voting intentions.

However, amidst all the numbers that were published, one specific data point caught my eye: Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) support in Quebec.

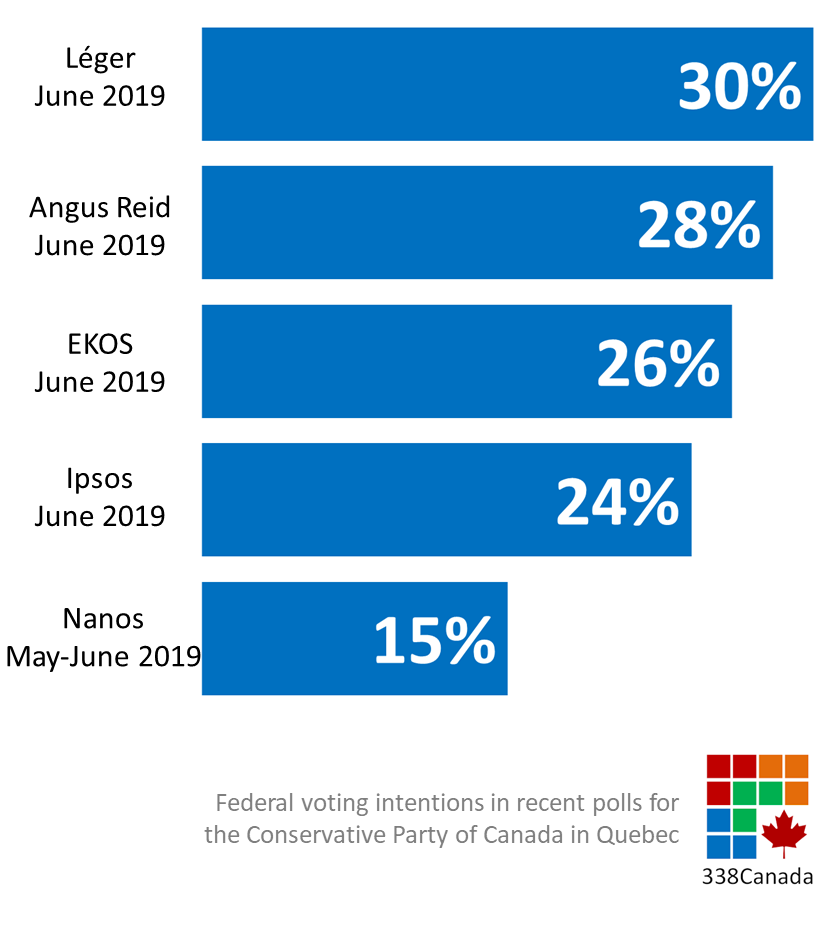

First, there was the Angus Reid Institute poll which suggested that the Conservatives had risen to an unexpected first-place statistical tie with the Liberals in Quebec (28 per cent for the CPC and 26 per cent for the Liberals), something no other pollster had yet to measure.

This had ‘outlier’ written all over it. But then the following week, Léger—which doesn’t have a history of overestimating the CPC—also measured the Conservatives in first place in Quebec with as much as 30 per cent support among decided and leaning voters.

In the past two weeks, EKOS and Ipsos also measured the Conservatives on the rise in Quebec, polling the CPC in the mid-20s (26 and 24 per cent, respectively). As of this writing, the Nanos weekly tracker has not yet detected such increasing support for the Tories in La Belle Province and still had the CPC at 15 per cent.

Are the Conservatives—slowly and quietly—making a breakthrough in Quebec?

Naturally, one must use caution when analyzing regional sub-samples. We must take each of these individual numbers with a grain of salt and look at the greater picture. By weighing and averaging all these polls, last Sunday’s 338 federal projection update estimates the CPC at an average of 24 per cent in Quebec.

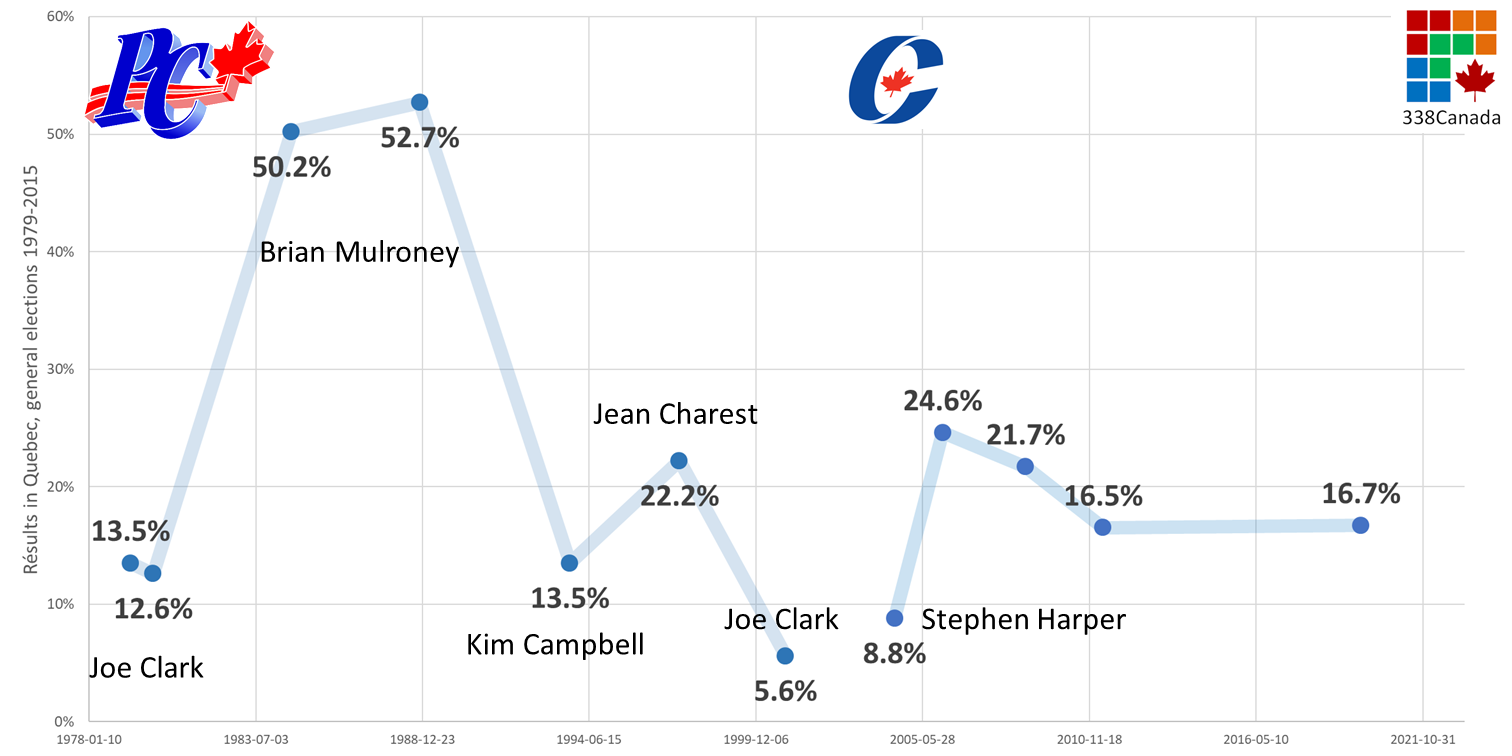

If these numbers above still seem relatively unremarkable, let us put them in historical context. Here are the general election results of the federal Conservatives in Quebec since 1979:

As you can see from the graph above, federal conservative parties have not fared too well in Quebec in the past 40 years, aside from Brian Mulroney’s two majority victories in 1984 and 1988. In fact, in eight general federal elections since Brian Mulroney’s re-election in 1988, federal conservative parties have never received more than a quarter of the Quebec vote. The closest to that mark was 24.6 per cent in 2006, which had produced a mere 10 Quebec seats for Stephen Harper’s first term as prime minister.

In the 2011 general election, back when the House of Commons had 308 seats (155 needed for a majority), the Harper-led Conservatives won a crushing 161 of 233 seats (69 per cent) outside of Quebec en route to an easy majority victory. Yet, despite its coast-to-coast victory, the CPC won only five of 75 Quebec seats.

“Stephen Harper has just shown proof that the Conservatives do not need Quebec to win a majority” was a common hot take following the 2011 general election. Yes, Harper won without Quebec; all it took was the worst electoral defeat in the history of the Liberal Party. It was an abnormal election.

In 2015, even though the Conservatives only received 16.7 per cent of the Quebec vote, they managed to win a very respectable 12 seats in the province, more than in any general election since 1988. Moreover, despite the loss on election night, Quebec was the only province where the Conservatives actually increased their share of the popular vote from 2011 (albeit modestly).

Last October, Quebecers elected the CAQ to a majority government with 37.5 per cent of the popular vote. While François Legault’s party, which has been polling in the mid-40s since the election, does not lean right as much as Jason Kenney’s United Conservatives or Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives, it’s the closest to a small-c conservative government Quebec has had in recent decades.

On several social fronts (including its recent religious symbol law), Legault’s CAQ and Trudeau’s Liberals are light years apart. Therefore, if the CPC is looking for a road map for potential gains next fall, the CAQ map—which conspicuously excludes Montreal—would constitute a fair start.

The polls in the next few weeks will help us find out whether this recent Conservative rise in Quebec is simply a statistical fluctuation or actual progress for the CPC. To be continued.