There’s lots at stake in this election. And lots of time to decide.

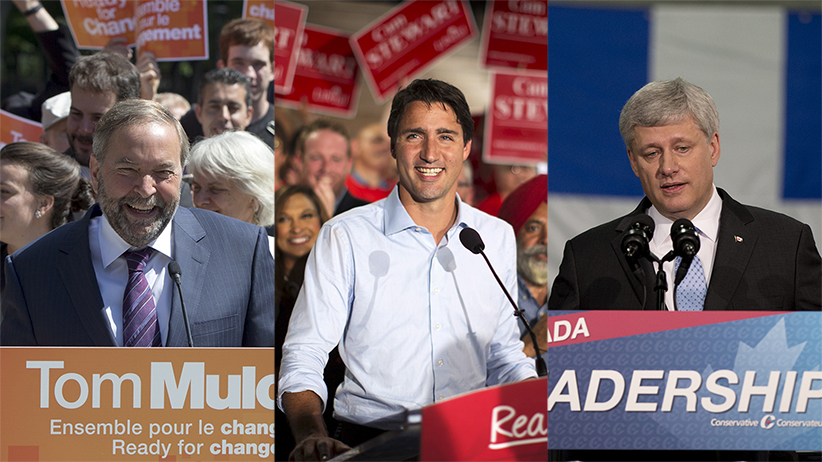

Canada has never had an election with three candidates so evenly matched—or so different in personality

Share

Much has been made of the fact that the 2015 federal election campaign will be Canada’s longest since the 19th century, when horse-powered ballot delivery necessitated voting periods that stretched over several months. But even if technology has improved, an 11-week campaign can still be put to good use today in the 21st century.

The 2015 federal election is shaping up to be one of the most consequential and interesting campaigns in Canadian history. This country has never had an election with three candidates for prime minister so evenly matched—or so markedly different in personality. Rarely have platforms and national visions of the main parties diverged as sharply as they do now. The vote could also have a significant impact on Canada’s role and reputation internationally. Given the stakes, Canadians should take all the time they need to make their choice on Oct. 19.

Related: Our primers on the 12 issues that will dominate the campaign

Since last weekend’s election call was telegraphed well in advance, the initial messages delivered by the leaders can be considered cameo versions of their campaign plans. Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau talked exclusively about his abiding interest in the middle class. “When the middle class does well, so does the entire country,” he said. Thomas Mulcair, NDP leader and putative front-runner, spent most of his time attacking the fiscal record of the current government, pointing to a string of deficit budgets and widespread insecurity in the labour market. Befitting his front-of-the-polls status, he also worked hard on maintaining a smile throughout.

For his part, Prime Minister Stephen Harper emphasized his government’s track record of tax cuts and fiscal probity at home. Yet he also dedicated considerable time to issues beyond our borders. “Jihadi terrorists have declared war on Canada and Canadians by name,” he reminded voters. He repeatedly mentioned Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. And, in media questions afterward, he reiterated his support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal. Trudeau, in contrast, had nothing to say about foreign policy in his election-opening remarks. Mulcair had little to say about international affairs other than he would ensure that Canada’s “reputation as a country is respected abroad”; his policies, however, include withdrawing from the international coalition fighting Islamic State.

Harper’s deliberate emphasis on foreign policy highlights what may be the biggest difference between incumbent and contenders. It is axiomatic that leaders arrive in office fixated on domestic problems and leave enmeshed in world affairs and, certainly, there is some of that in Harper’s political trajectory. But it is also true that Canada’s success and security are deeply enmeshed in international matters, where leadership and experience loom largest. This is undoubtedly Harper’s strongest suit.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

Of course, there are plenty of domestic issues that also reveal the wide policy space between the parties, particularly on family policy. Mulcair has vowed to create a new large-scale federal government mandate in daycare provision, with a long-term goal of one million $15/day child care spaces. Harper offers the exact opposite: a universal cash payout to families, regardless of child care needs. Trudeau seeks to split this difference with a middle-of-the-road policy, a new means-tested benefit. The fourth party in the race, Elizabeth May’s Greens, offers further diversity in policy, including a version of guaranteed annual income to combat persistent family poverty.

In terms of broad political urges, the NDP seeks to enlarge the role Ottawa plays in Canadians’ everyday lives, with activist changes to labour markets and fiscal policy. The Conservatives, having had nine years to craft domestic policy to their liking, stand on their record of smaller and less intrusive government, reduced taxes and limited overlap between federal and provincial jurisdictions. And after quickly dropping from front-runner to third place over the past year, Trudeau now presents himself as a hard-charging underdog intent on splitting the ideological difference between Harper and Mulcair with targeted social policies. Separated in this way, the various platforms offer distinct choices for Canadians on the size, scope and purpose of the federal government.

Beyond policy, this election will also turn on voters’ impressions of the leaders’ personalities. Trudeau’s easy charm is clearly his greatest advantage. Mulcair is trying earnestly to soften his former image of an angry populist, while Harper seems to have resigned himself to the fact that his cold and calculating approach to government has alienated many Canadians. Opposition leaders have seized on this antipathy as a reason why change is necessary. Each of them now has plenty of time to convince voters why her or she is best suited to deliver this change. (Although when they talk about change, they often mean undoing what Harper has already done. Both Mulcair and Trudeau, for example, promise to restore door-to-door mail delivery and return the retirement age for federal seniors’ programs from 67 to 65. Reversing either policy would be financial folly.)

Related: Where and how to watch Maclean’s National Leaders Debate

As much as the prospect of a lengthy election campaign may seem a chore to Canadians currently focused on enjoying their summer, the 2015 election is an important event that will require appropriate attention. Given the clash in style and substance among party leaders, the campaign should also offer great entertainment value along with its deep historical significance. We’ll want all 11 weeks.