Three key takeaways from Justin Trudeau’s testimony

The Prime Minister’s appearance to explain his latest ethics scandal revealed conflicting priorities, and that chaos is still possible in Canadian politics

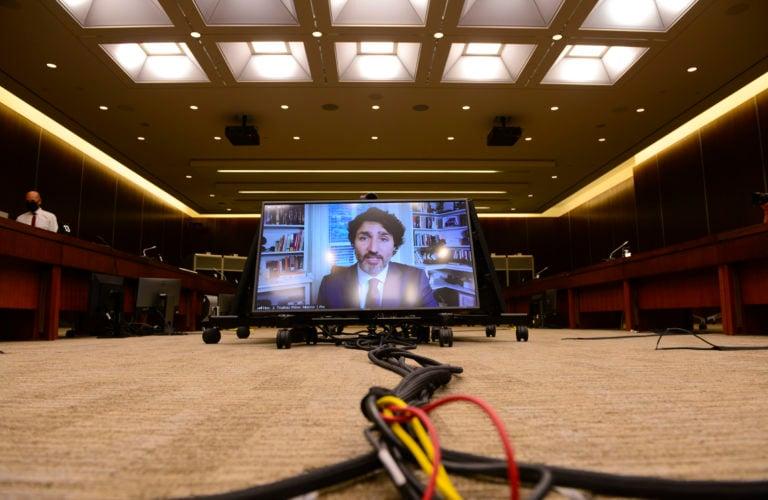

Trudeau appears as a witness via videoconference during a House of Commons finance committee on July 30, 2020 (CP/Sean Kilpatrick)

Share

The much-anticipated questioning of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his chief of staff, Katie Telford, finally played out on the country’s laptop screens and televisions Thursday afternoon.

It was MPs’ first opportunity to grill Trudeau on an ethics scandal during his five years as Prime Minister. They would be able to hear him explain, in his own words, how he and his government ended up partnering, to the tune of more than half a billion dollars, with a charity that has deep ties to his own family.

Alas, surely to the disappointment of the opposition, this was, for neither official, a dumpster fire in the style of Finance Minister Bill Morneau. He, in the early part of his own testimony last week, revealed that he’d paid back some $40,000 to WE Charity for free trips his family had historically taken with the organization, for which his daughter works.

But it did lead to some new insight in the PM’s timeline and decision-making, and new questions over his office’s involvement in the early stages of the program. Here are three takeaways from the day’s proceedings:

1. Trudeau describes a truncated timeline and conflicting priorities in his decision-making

In Trudeau’s testimony, he asserted that he was not aware of WE’s involvement in the implementation of a student grant program until the matter was to be raised at a cabinet meeting on May 8. Neither was Telford, she stated.

Several staffers in the Prime Minister’s Office had been aware of the program and the recommendation for WE to administer it before that. Telford declined to formally commit to releasing the names of a “handful” of PMO staffers, a sticking point for opposition MPs.

WE Charity wouldn’t sign a formal contribution agreement with the government until later in June. But on May 5, before the PM says he had knowledge of its involvement, the organization began working on the program. That was also the same day that a cabinet committee, sans Trudeau, had met to discuss it.

The knowledge that WE had already been chosen to administer the program led Trudeau to two conclusions, per his testimony.

He recognized it was possible that questions would be raised over his own family’s connections to the WE empire. And, in light of the perceptions stemming from those connections, he decided there should be greater scrutiny on the program.

Those two conclusions could have led Trudeau in a number of directions. He could have recognized that he should recuse himself, and asked his ministers to provide the due diligence he thought was required. He could have asked for a program scale-down, given his own instinct that the lower-capacity Canada Service Corps, within the public service, should administer such a program.

Instead, claiming to be seized by his own interest in youth issues, Trudeau decided to participate in the due diligence that his own perceived conflict-of-interest would demand, then sit at the cabinet table for the final rubber stamp. That due diligence, by the way, seems to have consisted of a single briefing by officials two weeks later—and Telford declined to go into specific detail as to what due diligence exactly meant in this case.

He now admits that this was a problematic rationale, whether or not you agree that there was an actual conflict-of-interest. Which he does not. Trudeau said he did “absolutely nothing” to influence the recommendation in the first place, and he strongly pushed back on the idea that the program would in any way benefit the Trudeau family members who had worked with, or received payments from, the WE organization.

2. The Prime Minister and his entourage are genuinely convinced of their own virtuousness. That leads to blind spots.

Canadians can decide whether or not they believe that Trudeau and Telford have their hearts in the right place, and how earnest are their treatises on the importance of supporting Canadian youth.

But concerns around financial help, youth mental health and whether we’re going to have a “lost generation,” as Telford put it, are easy to back up with data and were strenuously defended by both of them. And as confident as they were about their pure intentions, there was a rare flash of humility. “We’re not perfect,” Telford admitted, saying that none of this went the way it was supposed to have gone. “But we are committed to doing better.”

The enthusiasm for addressing problems facing youth would lead to several blind spots around finding solutions within the $9 billion envelope Trudeau announced on April 22. The ill-fated Canada Student Service Grant, whose details had not yet been nailed down, was announced as part of that package.

First, they underestimated how intense the questions would be over the appropriateness of outsourcing work to an organization deeply tied to Trudeau and Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s immediate families—even though the Prime Minister was well aware that questions would be asked and delayed its approval, according to his testimony. “We wanted to make sure that everybody was perfectly comfortable with it,” Telford said, referring to public servants and senior officials involved in the decision. The fact they arrived at perfect comfort is perhaps troubling.

Second, WE had been speaking with officials as recently as April about another, also costly, prospective program. While it is unclear whether its employees contravened lobbying rules through those engagements, the hearing Thursday made clear that nobody in the Prime Minister’s inner circle sought to clarify that point.

Third, much criticism around the program itself has questioned the virtue of paying students to volunteer, given that volunteerism is unpaid by definition. The amount they would’ve been paid was well short of minimum wage. But Trudeau flatly rejected that the spirit of volunteerism couldn’t be celebrated within such a structure.

Finally, Trudeau and Telford kept repeating that the cabinet’s decision was always a “binary choice”: Program? Or no program? It will perhaps strike Canadians as a little rich that there was no flexibility whatsoever in the program’s design, even as the government was contorting itself in myriad other ways to deliver pandemic-era programs.

3. Unscripted anarchy is still possible in Canadian politics.

Tired of endless talking points, scripted remarks and carefully-worded sparring? Happy to report that chaos is still very possible in Canada’s political life.

On Thursday this took the form of Chair Wayne Easter losing power during a wild thunderstorm. As Conservative MP Pierre Poilievre was hammering Trudeau on questions over financial benefits his family has received from WE, a Liberal MP, Sean Fraser, interjected to let the others know that Easter was offline, having lost power. He figured they might suspend.

But an NDP MP, Peter Julian, piped in with a procedural note: Actually, the committee’s vice-chair could take over the proceedings.

“That would be me,” Poilievre said. He then ceded the floor to “the member for Carleton”—himself.

The ensuing exchange between him, Trudeau—who, though cornered, declined to provide a dollar figure to Poilievre for the umpteenth time—and Liberals attempting to make points of order was entertaining, though short-lived. Easter returned and cajoled Poilievre saying it wasn’t the first time he tried to “put his lights out.”

Sure, that lawless display may have reminded you of the filibuster antics or question period heckling from days gone by. But in an era of banal Zoom calls, we’ve sort of missed that eye-rolling performance art. And if there was a moment on Thursday when popcorn was appropriate, it was then.