Who makes the decisions in Justin Trudeau’s Ottawa?

Paul Wells: Unless we understand how the government decided to team up with WE, we can’t be sure such things won’t happen again

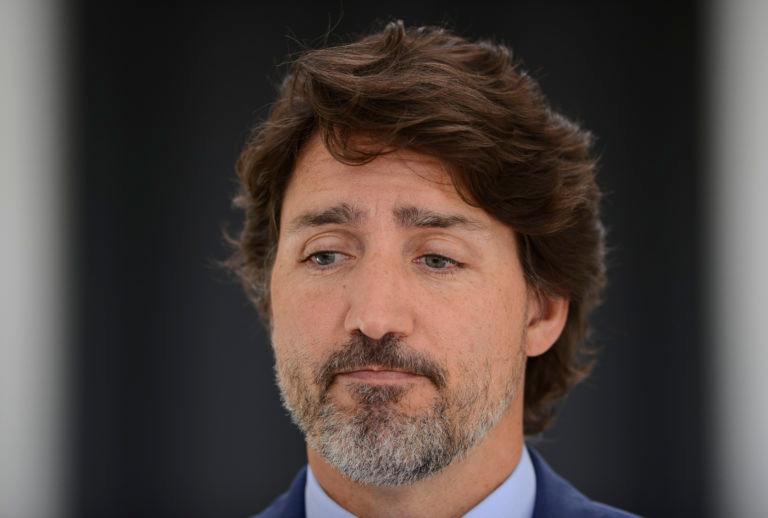

Trudeau holds a press conference at Rideau Cottage in Ottawa on July 13, 2020 (CP/Sean Kilpatrick)

Share

Well, that’s nice. The Prime Minister has thought about his choices. He feels bad about them.

“I made the mistake of not recusing myself from the discussion, right from the beginning,” Justin Trudeau told reporters at Rideau Cottage on Monday morning. The discussion in question was about whether WE Charity should run a large program designed to pay young people to volunteer. I know, they stop being volunteers at that point, but get past it, there’s a lot going on.

Turns out WE Charity’s social-enterprise doppelgänger, ME To WE, had paid assorted Trudeaus lots of money over several years for speaking gigs. And indeed, WE itself paid the Prime Minister’s mother and brother thousands of dollars directly, instead of letting ME To WE make the payments, a crucial distinction-without-a-difference that makes the apparent Trudeau family conflict of interest all the more direct.

When news of the speaker-gig payments broke on Thursday, assorted Twitter-based defenders of the Trudeaus, WE, or both promptly began arguing the speaker payments had nothing to do with the paid-volunteer program’s design, so there could be no problem that the program followed the payments. Trudeau was less eager to make such absurd arguments, and was quick to apologize at length for triggering a conflict whose existence his defenders had spent the weekend denying.

READ MORE: It’s time for Liberals to learn a lesson

“The mistake that we made was on me, and I take responsibility for it. We will continue to work very, very hard to deliver the program,” Trudeau told reporters.

This is nimble, as far as it goes, and unlike on previous occasions when the PM’s magnificently shaky judgment has been on display—the Aga Khan vacation, the India pageant, the SNC-Lavalin gang-up, the decades of compulsive blackface socializing—it actually wasn’t the worst reaction it would have been possible to imagine. Unlike his adoring Twitter defenders, Trudeau didn’t claim ME To WE is meaningfully distinct from WE, or that a payment to his mother’s speaker’s bureau is not the same as a payment to his mother, or that he is not, in fact, actually related to these other people named Trudeau. Instead he took it on the chin.

In so doing, at least for the length of a scrum, he might almost have succeeded in persuading some people that the moral universe of WE and the Canada Student Service Grant could be shrunk to the simple question of whether the Prime Minister should have “participated” in the “discussion.”

So it was just a bad day at the office? Some of the first questions after Trudeau’s mea culpa rursus (my fault yet again) participated in the same personalizing logic. “Do you think voters will forgive you?” was one. “How can you convince Canadians that this is a genuine apology?” was another.

But Trudeau’s role is only one question that arises, isn’t it? The ethics commissioner will decide on the formal question of conflict of interest, regardless of Trudeau’s feelings after the fact. Meanwhile there’s no evidence, and not much likelihood, that Trudeau bullied the WE mandate through, over the strenuous objections of an otherwise vigilant cabinet. Recruiting a secretive and litigious charity to disburse hundreds of millions of dollars in a novel program of untested design was a terrible idea whether or not Trudeau was there. And unless we understand how it happened, we can’t be sure such things won’t happen again. Indeed, it’s prudent to suppose they will.

So the germane questions, it seems to me, are about the culture of this government. How it makes decisions. How it works with the public service. How eager the government is to recruit like-minded collaborators. How gullible it is to being recruited by them.

So: the government, not just Trudeau, has claimed all along that teaming up with WE was the result of an open and transparent process. Fine. May we see the process? What were the program criteria? What organizations were considered? Did the public service say only WE could deliver this program? Great: show us the memos. (Campbell Clark in the Globe has written a few fine columns making arguments along these lines.)

“The public service has openly stated that it was their recommendation for the WE Charity to receive the contract for this program,” WE claimed in full-page newspaper ads on Monday. Really? When? Who in the public service stated this openly? Since so many of us seem to have missed it, can they say it again, in front of parliamentarians?

Trudeau refers to “discussions” from which he wishes he’d recused himself. Great. How many discussions? Who participated? Did nobody suggest this whole program design was a terrible idea? Would the decision have been different if Trudeau had pushed himself back from the virtual Zoom table? Recall that WE and the feds had already announced the demise of the collaboration before Trudeau’s conflict of interest became public knowledge. So the conflict of interest can’t be the only problem.

The questions in that last paragraph, incidentally, are handy for cabinet ministers and PMO staff to ask themselves, even if they refuse to answer them in public: If you’re there to raise the PM’s game by asking him the hard questions—or to protect him, by asking the hard questions while they’re still safe hypotheticals—in what sense can you be said to have done your job? After a failure this spectacular, how do you plan to behave differently next time? Because the cheerleading and the go-team-go, they seem to be producing mixed results so far.

These questions are also for the Deputy Prime Minister of Canada, whose appointment was advertised as a counterbalance to the Prime Minister’s worst instincts but whose weekend seems to have been spent, yet again, at a genteel distance from trouble. The Bloc leader has been calling for Chrystia Freeland to take over the Liberal leadership while Trudeau is investigated. Of course there’s no chance that this is because such a switch would make the Liberals more vulnerable in ridings the Bloc contests, right?

But partisan considerations in general are also a bit of a distraction from the matter at hand. Polls suggest that if the Liberal government fell this week (a hypothetical question, because there’s no sitting Parliament in which to hold a confidence vote) it would be returned with a comfortable majority. Someday the Conservatives should pause to wonder how they got so solidly on the wrong side of voter preferences, and why they content themselves with believing that a Stephen Harper with more smiles, or an Andrew Scheer who marches in pride parades, would fix what is becoming a fundamental mismatch between the party and the mood in the country’s population centres. That’s a rant for another day.

But government in Canada can’t be reduced to whether the popular team wins. It must also be about the choices any team makes while it’s there. And so far, whether Justin Trudeau is central to its decisions or not—a question about which there has always been more than a little uncertainty—this government is, consistently, the sort of government that makes Justin Trudeau-flavoured decisions. It’s getting way too easy for Liberals to blame the boss.