You’re not the voter you think you are

On political free will and Parliament Hill: Why we make the decisions we do at the ballot box, and how parties use that knowledge to try to woo us

Share

Calm, dispassionate, rational. You think about the candidates, the leaders, the histories of the parties. You consider the policies, the platforms, the promises. You weigh the evidence. You decide which party is best for Canada. You decide who to vote for.

Well, actually, no—you don’t. You just think you do.

That’s the bad news: you’ve long been misled. You’ve been told your rational brain is in charge. Not your gut. But the truth is that your gut is as much a source of your political decisions as your rational brain, and much of the time your gut—emotions, feelings, intuition—does its work outside of your awareness.

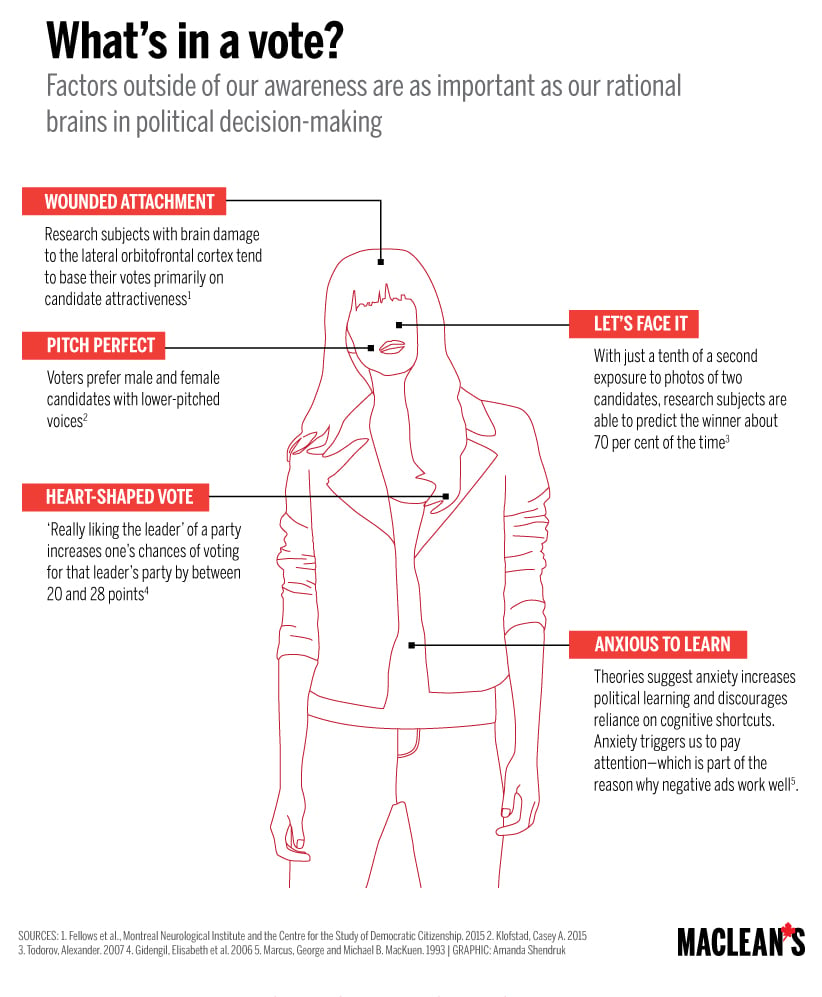

Yep. The faces of the candidates, the pitch of their voices, their gender and ethnicity and height; whether or not you believe in God, whether or not you’re hungry, whether you’re a lawyer or dock worker or school teacher; the effects of political advertising, the effects of issue framing or priming, the effects of your peer group; your partisanship, your family, your fears.

Related: Polling the lighter side of #elxn42

Any or all of these factors may impact how you think about political issues and how you vote—without you being any the wiser. And these are just a sampling of the dozens and dozens of such phenomena that scholars have discovered throughout decades of research into social and political psychology.

Now, the good news: you’re not alone. Most of us are susceptible to the same series of non-conscious, non-rational phenomena that determine our political opinions and our vote. So we’re united. We’re united in our predisposition to be manipulated by factors outside of our awareness—and in our ignorance of what they are and how they work.

As Canada’s 42nd federal election unfolds I’ll be writing a series of pieces explaining the world of political psychology. Through written work, infographics, and multimedia content, I’ll be relating research from the wondrous and strange world of social and political psychology to the current contest.

If all goes well, by the time you cast your ballot on Oct. 19, you’ll know more about the many considerations that affect where you mark that X. You might even end up making a better decision.

Related: Try Maclean’s Policy Face-Off Machine to find the party that you most align with

The legacy of the rational voter

I blame Descartes. He’s the 17th-century French philosopher who gave us Cartesian dualism—the idea that the mind and body are separate and independent. He argued that reason, which comes from the mind, is the source of our knowledge. His thinking laid the early groundwork for the suggestion that voters are or could be purely rational creatures. It was in part on this foundation that subsequent thinkers applied market logic to politics—giving us the economic rationality approach to politics that’s so common today.

In the 1950s, political scientist Anthony Downs built on this tradition. He wrote about how the rational choice theory of the day could be applied to political decision-making. He hypothesized that in a world of full information—where voters knew everything they needed to know to make a choice and in which that information was accurate—a voter could compare the expected utility (how good or valuable something is likely to be) of one choice against that of another in order to determine which was the most rational choice for her to make.

(Party X is promising me six kittens; Party Z is promising me five ducks. A duck is worth 1.5 kittens to me. Party Z it is!)

In a complementary theory from the time—one that employed the “spatial model” of decision-making—individuals were believed to have a series of issue preferences closer or further away to the position of any given party. Voters could plot points—like those on a graph—to find out which party they were “closest to,” which meant that parties would have an interest in approaching the bulk of voters that would find themselves clumped together in the middle (the so-called “median voters”).

Downs and his colleagues didn’t argue that this was necessarily how voters decide—plotting points on graphs, working out utility calculations. Researchers then, as now, knew that we live in a world of imperfect information and scarce resources. Yet many of us think of voters this way and we certainly tend to think of ourselves as, at least in general, making rational, deliberate decisions about our positions on the issues of the day and our decision about which party and candidate to vote for.

Which is understandable. When political parties pitch policies they often assume that their voters will make a rational decision about the value of that policy to them. The ducks might be tax cuts. The kittens might be child care. But the voter is given the benefit of the doubt.

And fair enough. Voters do sometimes make rational political decisions. Because despite what some philosophers or physicists might suggest, humans aren’t just passive vessels, passed back and forth between the omnipotent forces of the universe and the surreptitious dictatorship of our guts.

But we don’t always or entirely make political decisions based on rational calculations. In fact, most of the time, we don’t. Parties know this, too. They know that we’re not humanoid calculator machines who accept inputs, process them, and output the “right” decision—the most accurate, reliable, fitting, or true choice. We are way, way more complicated than that. And so are elections.

The socio-economic voter

Doubts about the rationality of voters aren’t new. In the 1940s and the 1950s researchers in the United States looked into the role that ethnicity, class, education, religion, and other structural life factors played in determining vote choice. They found that issues—where the party stood on taxes, the military, infrastructure spending, and so on—tended to be less important than where voters were coming from socio-economically.

So what about issues? If a vote is all about who you are and not what the parties were talking about, where did issues fit in? One breakthrough theory is known as the “funnel of causality.” It was developed by a group of political psychologists known as “the Michigan School” to explain how voters were affected by a combination of their life situation and the issues, candidates, and campaigns of the day.

The funnel starts at the wide end with socio-economic factors: those mentioned above, as well as other factors such as one’s parents and career. Next comes party identification—which team does the voter tend to cheer for? Then, just before someone chooses for whom to vote, the short-term factors of the day: the latest issues, the campaigns, the influence of family and friends, the candidates themselves. This approach balanced rational considerations with other factors drawn from the life and times of the voter. But as new research methods emerged, new considerations emerged.

The complex voter

The brain. Three-and-a-half pounds. Eighty billion neurons. Over 100 trillion synaptic connections. There’s a lot going on in there. Recent research in social and political psychology and neuroscience has highlighted the role of the certain brain regions, the non-conscious mind, and emotion in decision-making. The mind-body split that occurred during and persisted after Descartes’s time has started to be reversed in recent decades. Today researchers commonly look at the brain and body as a unified system that produces some unexpected phenomena.

“Motivated reasoning” is one such phenomenon and one of the most important findings of the last few decades. It occurs when individuals use emotion to make a decision aimed at some specific outcome. Now people rely on emotion to make decisions all the time. But much of the “motivation” in motivated reasoning is hidden—it’s unconscious. Something outside of his awareness motivates a person to make a certain kind of decision.

The motivation to get to this decision leads that person to selectively choose which facts he seeks out and which he believes; it leads him to warp those that don’t fit with the conclusion he’s after. Later, when asked to explain or justify our choice, he draws on reasons and explanations that he makes up after the fact! Again, this is outside of our awareness.

Also, as techniques and tools in neuroscience have become more sophisticated, and as more researchers from the social sciences co-operate with scientists, we are learning more and more about how certain regions of the brain and their formation are linked to our decisions. Some research, for instance, suggests that liberals and progressives have “different sorts” of brains. And a number of studies show that while human brains are malleable, once certain neural connections are made, they are unlikely to be rewired. We become our neural pathways. Or they become us. And we, or they, tend to stay that way.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

So what kind of voters are we?

None of this means that we voters—we humans—are fully determined by forces or structures outside of our control. But it does mean that we aren’t fully in charge of our own decisions and we’re certainly not the only ones piloting the ship of our life. We’re not determined, but we aren’t radically free and rational choosers either.

The better we understand who we are and what shapes us, the better we’ll be at making good decisions—including for whom to vote. So there’s no time like election time to start to understand the messy world of political and social psychology.

Follow @David_Moscrop on Twitter.