Afghanistan vet Chris Downey on trekking to the Pole with Prince Harry

‘Why wouldn’t I want to walk 300 km at minus 50 pulling my own sled? That sounds like a good time to me’

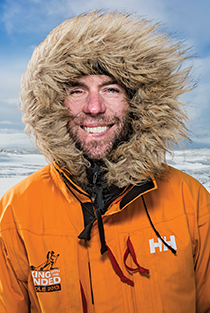

Petter Nyquist/Walking With The Wounded

Share

It was Chris Downey’s first tour of Afghanistan. He was one month in when, while on foot, the 28-year-old was blasted by an IED. His friend was killed, and he spent three months in hospital and more than two more years recovering. When the email came from Soldier On, a charity providing career counselling for wounded veterans, about a trek to the South Pole, he decided it would be a fitting tribute to his fallen comrade.

Q: Why did you join the Forces?

A:It’s what I’ve wanted to do since as far back as I can remember. There are pictures of me as a kid, three years old, dressed in my dad’s army stuff. My father was in the airborne regiment. At eight years old, I was in cadets. There was nothing else I wanted to do.

Q: Tell me what happened in Afghanistan.

A:It was May 3, 2010. I was part of an IED [improvised explosive device] team, which is basically responsible for getting rid of roadside bombs. On that day, we had to be on foot, because our vehicles couldn’t get there. Craig [Douglas Craig Blake], my teammate, successfully did his job and, when it was time to return to our vehicles—a two-kilometre hike—about halfway back, we were hit by an IED. It instantly killed Craig. I was about seven feet behind him, so I took a good chunk of it. I never lost consciousness. I couldn’t see. I could just hear and smell everything. I could feel my legs burning from the shrapnel. I couldn’t recognize any voices and started yelling out. That’s when my team leader started talking to me to keep me calm. It took about an hour to get me into surgery, and that’s where I went into 12 to 14 hours of surgery right away and woke up in Germany three days later. As for my injuries, I essentially lost my right eye. My jaw shattered. I lost parts of my gum and all my front teeth. I had hundreds of lacerations and burns. My right arm and right hand were completely mangled. And also, I had a collapsed lung.

Q: How has life been since that day?

A:The initial few weeks after were pretty brutal, working so hard just to survive and breathe, but I got really lucky. I had the right five people in Germany: five Canadian medics. They knew I loved challenges and wasn’t going to sit around. Even though I couldn’t move my right arm much, or see or talk, they started making me do things for myself, like clearing my throat through the [tracheotomy tube]. My life really started after that day—the things I’ve done, the places I’ve been. The pure joy I have for life now is irreplaceable.

Q: Speaking of the places you’ve been, how did you get to be part of the South Pole Allied Challenge?

A: Walking With the Wounded reached out to several charities, one being Soldier On in Canada. Soldier On sent an email asking if anybody was interested. I wrote back: “Sure, why not?” Why wouldn’t I want to walk 300 km at -50° pulling my own sled? That sounds like a good time. They selected eight Canadians to do interviews. From there, they selected three. The three of us, along with other candidates from the U.S., Australia and the U.K., went to Iceland for 2½ weeks of training, mini-expeditions and a final selection. They had to bring the team down to four: two Canadians and two Australians. I was lucky enough to be one of those two.

Q: What kind of training did you do on your own to prepare?

A: The day after the interviews, when I flew back to Cold Lake [Alta.], I built my own pulk [a small toboggan]. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, I was walking from the base to my home—13 km—pulling a sled with 150 lb. Once the warmer weather hit, I started doing long-distance pulling tires, including doing the Army Run half-marathon with a tire behind me. Every night, I was watching a movie or a couple of shows while on the elliptical for 2½ to three hours. Sometimes I would turn my treadmill toward the wall and just walk with nothing to look at, just trying to mentally prepare myself for the nothingness of Antarctica.

Q: What were the conditions like in Antarctica?

A: When you initially land in Novo [the Russian station on the coast], it’s only about -5°—nothing extreme for us Canadians. From there, they flew us up to the 87th parallel, which is where we started the race. I think the warmest there was -35 without the wind. For Alex [fellow Canadian Alexandre Beaudin-D’Anjou] and me, we had experienced those colds before, so it wasn’t a shock. Mentally, it was very challenging, in that the way to ski and the way to maintain your body temperature goes against everything we know. Here, we dress nice and warm, but there, because you’re physically moving all day, you didn’t want to get warm. Getting up in the morning, I would take off layers to the point where I was wearing a thin layer against my skin, and then just my shell, and that was it. The skiing and carrying your pulk created so much heat that you had no choice, or you’d sweat and start to freeze.

Q: What was the hardest day for you?

A: On the second day, I had so many problems breathing, the doctor pulled me out to get oxygen and some rest. Luckily, I got to go back the very next day. It only lasted for about 27 hours.

Q: What happened?

A: The altitude got to me. I was skiing perfectly fine, listening to music and having a great day. Next thing I knew, I was on the ground and [my teammates were] pulling my head up and taking my skis off. I passed out—first time in my life. The doctor took about an hour and a half to get there, but once he did, they got oxygen on me and I started feeling better right away. Just to make sure, they pulled me back to the main camp and let me rest overnight.

Q: What was it like to walk for hours a day in such a harsh environment?

A: When we were there, you really just got lost in your head. I had an iPod playing the whole time, so I had music and audiobooks. I actually had a book called Alone on the Ice: The Greatest Survival Story in the History of Exploration, one of the most brutal survival stories ever, and I played that for two days. It was a good way for me to completely lose myself in the environment. My body was just doing the mechanics, but my mind was completely outside of that environment, so the skiing days went by really fast. The struggles were still there. I had a lot of chest and breathing issues with the altitude.

Q: How many hours would you walk each day?

A: It was eight hours a day and our team was covering about 24 km a day. Of course, that was until we decided the race was no longer going to be part of it and then, after that, we all skied together and that mileage changed.

Q: How many days into the trip was the race aspect called off?

A: We had already covered 130 km [of 335 km]. It was five days or so. Just the number of injuries, it was taking away from enjoying the moment. And really, the goal was for all 12 wounded to stand at the South Pole together and to spread the message that, if you work hard enough, have the right support and the right opportunities, then there’s nothing that you can’t do.

Q: What was camp like? What did you eat?

A: Every night, we’d set up our tent, break up some blocks of ice or hard snow, and get in. We had a small stove that we would turn on and start melting snow. It’s the only way you get water. It’s also the only way to eat. We had freeze-dried food, the kind you add water to and let cook for a bit. That was basically it. You spent your night preparing for the next day. You boil water to fill your thermoses—we carried about 2½ litres of water a day to drink—ate your meal and dried off your gear. We listened to music, played cards and talked a lot. The tent is quite amazing. It could be -50 outside and, just because of the continuous sun, it warmed up the tent enough that we could sit in there comfortably. Every night, I wore a pair of fleece pants and a fleece shirt. That was it, sometimes with no socks on—never a toque, no gloves, sitting on top of my sleeping bag. That’s how much the sun heated up these tents. It was a little paradise. It actually got to the point where, while you were skiing, all you could think of was to get in that tent.

Q: One person who got a lot of attention for this trip was Prince Harry. What was it like skiing next to him?

A: It was great. Once we were there and all together, he was just another soldier. It was like hanging out with one of the guys. We didn’t feel his status from the outside world. He’s pulling his own stuff. He was treading through every inch like we were, struggling like we were, telling jokes, laughing. We talked about Afghanistan, sports. He’s just a regular guy.

Q: Describe what it was like to reach the South Pole.

A: It was extremely emotional. From the day I started this, I said I would reserve the last kilometre for [Craig] and me. That was something for me, to finally say my goodbye, something I never had the chance to do because of all the time I spent in the hospital. I never made the funeral. At about 1.5 km to go, I stopped, pulled out a Canadian flag and laid it over the pulk, just like we do for the coffins when we lose somebody overseas or in combat. On top of that, I put a picture of Craig, a diver’s coin, and a bracelet he had made—one that I was wearing the day I got hit. I skied next to everybody, making sure that the footsteps I was taking were just for him and me. I spent the last kilometre talking to him and thanking him. By the time I reached the Pole, I was in tears. It just came rushing through. I had this amazing goodbye to my friend, which was exactly what I needed in the perfect place to do it. And then I started thinking of my brother, my mom, my dad, every single person who had gotten me there. Once I got ahold of my emotions, Alex and I started having fun. I did the traditional handstand, so I could say I was holding the world. I ran around the Pole, so I could say I ran around the world. It was a celebration.

Q: What will be your next adventure?

A: I’ll be running in the London Marathon as part of the Walking With the Wounded. That will be my first marathon. I’m also hoping to take two wounded soldiers and two abled soldiers to the North Pole in April 2015. I want to do this because we fight together; some of us get hurt, but then we recover together.