Ultra-partisan social media is an addictive hazard—and detox is a last resort

When one user suffered a panic attack after a night of online raging, his doctor urged him to cut out political Facebook usage. He did unplug, for a while at least.

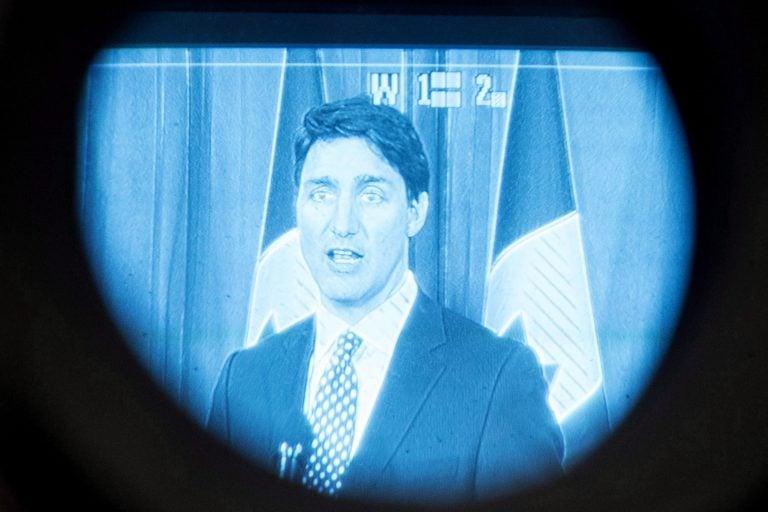

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is seen through the eye piece of a television camera, as he takes questions from the media after addressing the UPS Conference in Toronto on Wednesday March 21, 2018. (Chris Young/CP)

Share

It was a before-bed habit for Regina paint store owner Don Skaar, and one he yielded to at other times during the day: a trip through his Facebook news feed and his favourite political groups. Scrolling, scanning, clicking. Scrolling, typing, liking, scanning.

On one Friday night, thoughts of carbon taxes, recession and Justin Trudeau kept rolling through his mind, as did his news feed: scrolling, scanning, typing, liking. Scanning, liking, clicking. Scanning, scrolling, liking, scanning, scanning, scrolling-scanning-scrolling-scrollingscrollingscrollingscrollingscanning—stop.

“I woke up late Saturday morning just paralyzed with fear,” Skaar recalls. He’d gotten wound up before from the conservative outrage and news he was reading. But this time, Skaar’s brain overdosed on this unfiltered intoxicant. He found himself succumbing to the near-apocalyptic vitriol being shared with him on social media—like, really, was the state of politics, the economy, the country really this bad? It gave the single father of two a full-blown anxiety attack. “I was terrified the world was going to end.”

READ: The angry, radical right

Skaar’s doctor put the 45-year-old on new medication and urged him to detox from political Facebook usage, getting off several pages he’d frequent and avoiding the partisan debates. For his mental health, he did unplug, for a while at least.

At the time of Skaar’s personal reckoning, Saskatchewan’s economic downturn had begun, but his paint store seemed to be pulling through, despite the normal seasonal slump. His fears were stirred by the messages flooding his daily stream of information: a mess of hyperbolic panic over federal tax hikes, environmental policies and the paranoia that Canada’s Greece-like economic collapse was imminent.

WATCH: Zuckerberg: ‘Sorry’ For ‘Major Breach of Trust’

Not only do some social media users crave the most shocking, outrageous and overblown articles and images, but so do the social platforms themselves: the more likes, shares or retweets, the more likely you are to see it at the top of your news feed. Political pressure groups and interests have long exploited this: the more you panic, the more you click and share, ensuring others see the same thing. The recent scandal involving Facebook and Cambridge Analytica featured key players boasting about manipulating users by tweaking their fears and anxieties to further polarize discussions. It creates imagined realms where everyone on the other side is crooked and corrupt; the walls of one’s echo chamber become more and more galvanized.

In some situations, the alarmist mess on social media can help send people to extremes. A North Carolina man, shocked by hoax stories of a Democrat-led pedophile ring at a Washington, D.C., pizza parlour, visited it with an assault rifle (fortunately, no one was hurt). A disaffected Illinois man, known by friends for sharing pro-Bernie Sanders and imprison-Trump material online, shot at a Republican congressmen’s baseball practice last June, wounding two people. With increasing frequency come announcements that Canadian police charge people for making death threats—mainly on Twitter or Facebook—against the Prime Minister and other political leaders.

READ: Today’s political partisanship is hurting Canada’s best and brightest

Skaar didn’t act. He froze.

Toronto psychologist Nicole McCance routinely sees clients whose lives suffer from the excesses of social media—disengaged couples glued to their phones instead of each other, and people who obsess over friends’ validating likes and comments.

Then there are those who go down social media’s political rabbit holes and land in a unique category of risk. What they do when they’re bored, to numb out, winds up raising their blood pressure instead. People who are already anxious find it hard to help themselves, McCance says, and they begin to feel powerless and anticipate the worst—followed by irritability, anger, sleeplessness and panic. “Somebody who tends to worry, I’ve noticed it gives them this false sense of control to be an information seeker,” she says. “But really, in the end, they’re just more panicked. They’re absolutely overdosing on this stuff.”

Canadians are three times more likely to believe Facebook has a negative influence on politics and public discourse than to think its impact is positive, according to a survey in March by the Angus Reid Institute. Yet even in the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, only 10 per cent of respondents said they’d delete or take a break from their accounts; some others would slow down their usage, but most would merely tweak their privacy settings or keep using the platform as is. For the many who see Facebook as a more benign force in society, it’s a hard cord to cut. If it’s not an addictive political forum, it’s where people keep up with high school friends and former co-workers, play games, solicit travel tips, find second-hand maternity clothing and so much more. But the Canadians who see Facebook as a negative influence on politics and public discourse are also far more willing to suspend or scrap their accounts after the divulged-data scandal, the Angus Reid study shows.

Shachi Kurl, executive director of Angus Reid, recalls one time the political nastiness on Facebook became too overwhelming even for her, a political junkie and commentator. “At the height of the North American freak-out about the U.S. election, all my Facebook ‘friends’ were just posting Hillary, Trump, Hillary, Trump, all through my stream, and I remember just posting: ‘Hey, friends, can we not make Facebook great again?’ ” she says.

READ: Facebook still has Canadians hooked, even if they’re mad about Cambridge Analytica

A poll by the American Psychological Association (APA) after Donald Trump’s victory showed that more than half of Americans found the political climate was a somewhat or very significant source of stress. The news is hard to escape, but those who expose themselves to a bigger blast of it can wind up worse off—nearly four in 10 adults told the APA that social media discussions about politics and culture caused them stress, and those more likely to use apps reported such problems more often that those who didn’t. Thirty-nine per cent of Americans avoided social media to reduce their politics-related anxiety, according to a survey last year by Radius Global Market Research. That’s the advice McCance dispenses, and that Skaar received from his doctor in Regina.

Skaar had always been conservative, but he wouldn’t have described himself as politically engaged until about four years ago, when he started refereeing for Saskatchewan roller derby leagues. He was really good at the madcap whistle work, but his new peers skewed far more leftie than he was used to. On Facebook, he’d chafe at memes that called Stephen Harper an idiot. He’d push back, argue back, meme back, and ignored his father’s advice that there are two things you should never talk about with friends: religion and politics. “It started eroding some relationships,” he says.

The anxiety attack, which hit in January 2016—a few months after Trudeau’s election—helped Skaar realize he needed to step away, as his doctor had advised. “I think I needed to get out of the pool for a bit. I was getting a bit waterlogged with information,” he says. So he tuned out the political chatter, but only for a while. In the fall of 2017, he was tweeting epithets to Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Trudeau and Gerry Butts, one of the PM’s aides. The nastiest stuff was directed at Clinton: he called her a cancer on mankind and made other remarks with threatening overtones. Twitter banned him for a week. On a chronically fury-ridden conservative (and popular) Facebook group called the Republic of Western Canada, someone posted thinly veiled threats against a prominent Canadian politician. Skaar chimed in supportively at the time—but gasped when Maclean’s read him back his comment. “I’m definitely not serious. I would love to retract that if I could.”

A trip through that comment thread shows how much of a support group Facebook can become for the doom-minded. The original post garnered 476 likes and 141 comments, almost all of them supportive of the dark suggestion. (It was originally posted by a Winnipegger who has insisted, incorrectly, that Trudeau is a Muslim extremist, while worrying publicly that his grandkids “will have to live under Satanist brutal sharia law.” He says RCMP visited his house to warn him over some of his Twitter posts earlier this year.) Commenters called for drastic action as a way to stop “mass” immigration, Western alienation, the compensation for Omar Khadr’s mistreatment and other grievances. A few posters urged against harbouring such extreme, violent antipathy; others rebuked those moderate voices for urging decency. It’s all “mass hysteria,” way too far, Skaar says.

Not long after his Twitter suspension, he deleted the Republic forum from his feed. He only logs on to Facebook for friend and family updates. He’s still on Twitter, too, but only follows it to keep up with cryptocurrency news. He’s happy spending time with family and friends rather than getting likes from strangers online and alienating Facebook friends, and knowing far less of the memes and minutiae of politics. “If I am stressed about anything, it won’t be that, that’s for sure,” he says.

Still, the angst and fear has left an imprint on his mind. He’s contemplating selling the paint shop and moving to the United States, far from this country’s current political leadership but also, alas, from his two children. Maybe they’ll come into financial hardship and join him down south, he muses. “This country’s going to hell in a handbasket,” Skaar says. “I don’t have much hope for it.”