Elizabeth Warren, once at the back of the pack, is rallying like a contender

All but undone by her bogus ancestry claims, Elizabeth Warren now draws adoring crowds in the Dems’ nomination race with her agenda for radical reform. Can she complete the comeback?

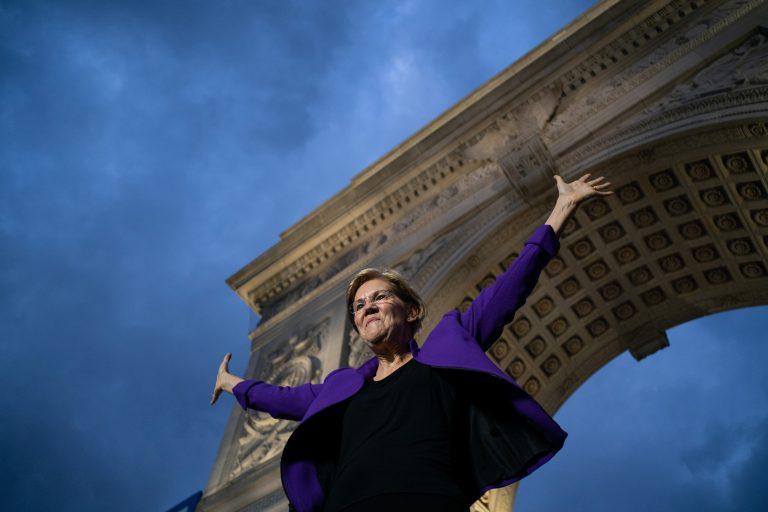

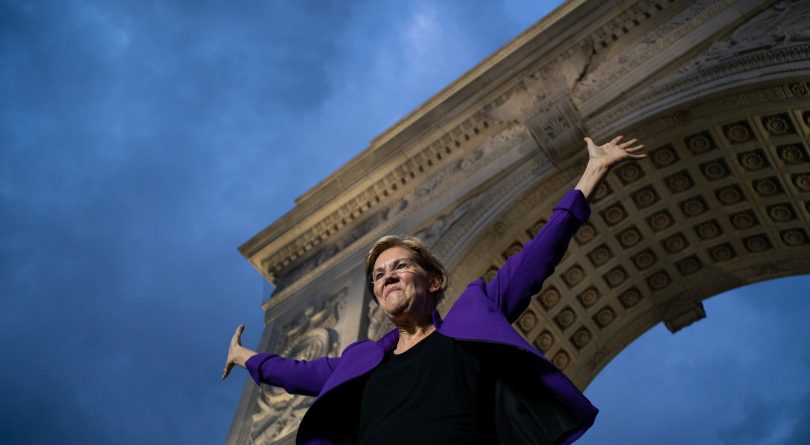

Sen. Elizabeth Warren during a rally at Washington Square Park in Manhattan on Sept. 16, 2019. (Todd Heisler/The New York Times/Redux)

Share

The U.S. presidential aspirant who wants the one per cent to tithe two per cent to pay for a sky full of pies is a 70-year-old white woman who is rising unimpeded by her age, her sex and the repeated lie embedded in her life story.

For Sen. Elizabeth Warren, bursting out of Boston onto the national soapbox by way of a “ragged-edge” Oklahoma girlhood, late summer has reaped a ripening of clarity, energy, vivacity and popularity. A millionaire leftist who sees deceit and conspiracy wherever she peeks, Sen. Warren has been gaining rapidly in the steeplechase for the Democratic nomination on a platform of skimming the uber-rich to provide the proletariat with free college, free medical care and a crime-free government. All she asks is two cents on the dollar from everyone with $50 million in the bank, once a year till kingdom come.

“What can we do with two cents?” Warren’s manifesto asks. And answers: “Universal child care for every baby in this country, age zero to five. Raise the wages of every child care worker and preschool teacher in America. Make technical school, community college and four-year college tuition-free for everyone who wants to get an education. And cancel student loan debt for 95 per cent of people who have it.”

READ MORE: Elizabeth Warren, haunted by ghosts of sexism past

“I’m a fan of hers,” responds Karen Altfest of Altfest Wealth Management on Park Avenue in New York. “She’s a very courageous person. But she has to develop her policies more fully. Is she going to have a team of professionals like ICE who go into people’s’ houses and appraise their paintings, their boats, their cars and their jewellery? Any part of what she says is possible. All of it at once is not.”

“She’s vibrant, she’s energetic, she’s a great speaker, she’s on point, she must have been a great professor, but I really fear her as president,” says Jay Diesing, a wealth manager in the billionaires’ beach haven of Southampton, N.Y. “This is just another version of a liberal Donald Trump vilifying another group and hoping that it will get her elected. The reassuring thing is that the government is able to get so little done, there’s no reason to expect they would get this done, either.”

“I know what’s broken; I’ve got a plan to fix it,” Elizabeth Warren boasts several times a day on the campaign trail, and more Americans than ever are buying what she says. Late September finds her a close and surging second to former vice-president Joe Biden in the public-opinion polls, with Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont a rusted-out third and every other female in the derby—and every contender younger than 70—far behind. “The nomination is Warren’s to lose,” declares the right-wing Drudge Report, eagerly counting down the minutes—as the entire U.S. press corps seems to be doing—until Joe Biden commits an irredeemable blunder and leaves the field clear.

Elizabeth Ann Warren, the junior senator from Massachusetts, used to be a Republican, but that was some time ago and she doesn’t talk about it. She made her career as a professor of bankruptcy law at ivory-tower Harvard but likes to present herself as the starry-eyed, married-at-19 daughter of a Sooner State janitor and a mail-order clerk at Sears: “I fell in lo-o-ove,” she sings. (That teenage marriage ended after 10 years. Sen. Warren has been married since 1980 to a scholar who teaches legal history at Harvard.)

A woman who is not afraid to be photographed with a beer in her mitt, Warren is fierce, she is focused, she is a mom of two who once worked as a special-education teacher, and she repeatedly fibbed her ethnicity as “Native American”—on her Harvard biography, on her bid to be admitted to the Texas Bar, even in a cookbook—until Donald Trump attacked her as a fraud and the pure-wool Cherokee Nation put a stop to her connivance. More about that later.

Now it is autumn, and Warren is in Washington Square Park in New York City—east of libertine Greenwich Village, north of the Wall Street crooks she decries at every turn—diagnosing the man she hopes to overthrow next November as “corruption in the flesh.”

So much for Michelle Obama’s buttery vow to Democrats in 2016 that “when they go low, we go high.” If the 2020 final turns out to be Warren versus Trump, it is going to be the nastiest New York-Boston smackdown since Pedro Martínez body-slammed old Don Zimmer along the first-base line in the 2003 playoffs.

“As bad as things are,” Warren says in Manhattan, with 20,000 committed or just-curious New Yorkers in the crowd, “we have to recognize that our problems didn’t start with Donald Trump. He made them worse, but we need to take a deep breath and recognize that a country that elects Donald Trump is already in serious trouble.”

America’s trouble, Sen. Warren has maintained since she became the first declared Democratic candidate in February 2019—and for years before that—is corruption: corrupt banks, corrupt politicians, corrupt lobbyists, corrupt companies, corruption everywhere.

“Americans are killed by floods and fires in a rapidly warming planet. Why?” Warren snaps in New York. “Because huge fossil fuel corporations have bought off our government.

“Americans are killed with unthinkable speed and efficiency in our streets and stores and schools. Why? Because the gun industry has bought off our government.

“Americans are dying because they can’t afford to fill prescriptions or pay for treatment. Why? Because health insurance companies and drug companies have bought off our government.”

Her solution? “End lobbying as we know it,” prohibit civil servants from owning outside businesses … and tax the smirking rich.

“Two cents! Two cents!” the crowd concurs, much as men and women thrill to “Build the wall!” and “CNN sucks!” in other places at other times.

Baiting 20,000 humans into Washington Square is not an extraordinary feat. Sen. Sanders claimed an audience of 27,000 here in 2016, and the park has been chocked at all hours by lovers, artists, poets, freethinkers, dope smokers, freaks, hippies and intellectuals—everyone, therefore, except Republicans—since the famous archway honouring the first U.S. president was erected in 1889.

But Warren and her following commune on a higher level. The call-and-answer, the chanting of arcane talking points, the stamina of the believers mark her as the rare candidate in the Dems’ field with alchemical appeal. The senator promises a snapshot and a few kind words to every last fan willing to queue up. As her crowds get bigger, that’s becoming a problem. In New York, four hours go by before an exhausted Warren exhausts the selfie line.

“She has never once said, ‘Let’s take upper-class people and make them middle class,’” reasons Dr. Lisa Baker, a New York pediatrician and one of the Warren supporters in the crowd. “I do believe that the power in our country is concentrated in the hands of the few, but that doesn’t mean that it is rigged.”

“If you had fifty million, would you give her two per cent a year?” Baker is asked.

“Two per cent of imaginary money?” she laughs. “Of course I would!”

READ MORE: Don’t count out Andrew Yang, the populist technocrat who wants to be president

As proof of her personal immunity to tainted lucre, Elizabeth Warren now declines campaign contributions from wealthy “bundlers” and political action committees. The emphasis is on “now.” Former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell—a fellow Democrat—called her out in a September opinion article.

“The senator appears to be trying to have it both ways,” Rendell wrote. “Get the political upside from eschewing donations from higher-level donors and running a grass-roots campaign, while at the same time using money obtained from those donors in 2018. I like Elizabeth Warren. I like her a lot. Too bad she’s a hypocrite.”

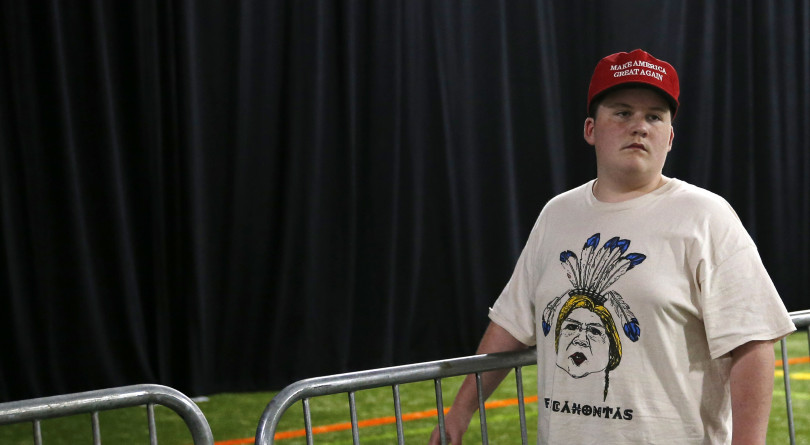

It is not Elizabeth Ann Warren’s first encounter with the H-word. As soon as Donald Trump sensed that a woman who repeatedly claimed Cherokee ancestry on the flimsy basis of “family stories” might present a formidable challenge to his re-election, he sprang into birther mode—well-practised after his racist denials of Barack Obama’s Hawaiian nativity—and defamed Ms. Warren as “Pocahontas.” The name caught, and the fallout rocked both the pretender and the Indigenous people who had been forced to walk the Trail of Tears, back in the 1840s.

“I’m not a tribal citizen,” Warren finally conceded in early 2019 after a DNA test—her gamble to call Trump’s bluff—revealed only a one-1,000th tinge of possible Indigenous ancestry. “My apology is an apology for not having been more sensitive about tribal citizenship and tribal sovereignty.”

It’s a beautiful day in the Hamptons. If you can afford to live in the Hamptons, it’s always a beautiful day. The sun is yellow, the strand is pearly, and the tennis courts and the Benjamins are green.

“Is Elizabeth Warren correct to say that the system is corruptly rigged against the middle class?” a Maclean’s reporter asks a retired Wall Street executive whose cottage on the southern fork of the eastern end of Long Island once was listed for more than US$30 million. (He has requested not to be identified for this story.)

“There is no question that big corporations have extensive influence,” he answers. “Whether it’s corrupt, or whether it’s legit, that’s a matter of the particular instance. But I don’t think that the connectivity that Elizabeth Warren makes between corporations and the poor ‘little guy’ is true.

“Big corporations hire the little guy and provide jobs and benefits. What’s really stacked against the little guy are technology, globalization and the horrendous quality of pre-college education across the country. Unfortunately, Warren’s rhetoric deflects attention from these macro realities. This thing she preaches about—the big guy against the little guy—is clearly a political ploy. Trump plays the same game with immigration.”

“I think there’s definitely a feeling of an escalation,” says Jay Diesing, the wealth manager and president of the Southampton Association, a civic and charitable organization. “I also feel that not all the people here are ‘old money’—a lot of them are people who worked hard their whole lives and maybe weren’t born with all the attributes that Liz Warren thinks they had.

“There are definitely ways that people would find to hide from that sort of tax. There is also a feeling that the truly rich—the billionaires—won’t end up paying anything at all. I just think that there must be some other way that Warren could think of that wouldn’t divide the nation.”

“Who frightens you more—Warren or Sanders?” Jay Diesing is asked.

“I don’t think I see a difference,” he replies. “When you’re facing execution, I’m not sure the method is all that important.”

“It has gotten to the point where a small percentage of our people have taken part in the growth of this country, and others haven’t really made large gains, and she’s politicking on that,” says Lewis Altfest, who (literally) wrote the university textbook on wealth management and estate planning. “I don’t think she hates the rich. She may think that some rich people are evil. But I don’t see her as a Bolshevik.

READ MORE: And how is Trump after an insane, surreal week? Couldn’t be better.

“She’s completely rational,” Altfest continues. “She’s not a hothead like Bernie—she has a more cold-blooded way of changing things. But it is going to be difficult for her. People are not interested in just turning things over.”

“Can she beat Trump?” Karen and Lewis Altfest are asked on Park Avenue, New York City.

“If she can capture the public imagination, yes,” Karen Altfest says.

“She’s got to get the American worker to look at her as not a spaced-out person,” says her husband, Lew.

“You could argue that two per cent is not necessarily a bad thing and won’t do any harm,” agrees our Hamptons zillionaire. “Somebody with 50 million could probably afford the one million. But two per cent for 15 years is a 30 per cent drag on your assets. I’d fight it like hell.”

The rich man draws breath.

“‘Two cents! Two cents!’” he sniffs. “That’s fabulous. That’s like ‘Lock her up!’”

In mid-September, a formal, moving ceremony is held in Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol to unveil an effigy of a 19th-century Indigenous statesman named Chief Standing Bear, a Ponca from Nebraska whose people were forced to move to Indian Territory, as the future state of Oklahoma then was known. “I am a man,” Standing Bear told a federal judge when he was arrested for leaving his reservation to return to tribal soil to bury his son, and the jurist agreed. It was the first time in U.S. history that a Native American was ascribed the legal status of “person.”

A few feet away, in the Rotunda, is the giant canvas of The Baptism of Pocahontas that has hung in the Capitol since 1840. Cartooned in later centuries, the real woman was an Algonkian of 17th-century Virginia who was brought as an exemplar of the miracle of Christian conversion to England, where she died at the age of 21.

As part of the ceremony, a Native American named Andrew Thompson, a Choctaw from Oklahoma who served soul-searing combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan with the 10th Mountain Division of the United States Army, has been invited to dance. “Culture helps to bring back the person I was,” Staff Sgt. Thompson says.

“I know many people who have a false sense of being someone they are not,” he answers, when asked about Elizabeth Warren. “A lie is a lie. If you are, you are. If you’re not, you’re not. She has to go to bed knowing her own truth.”

“What Trump says about her,” the ex-soldier muses. “Is it fair to the real Pocahontas?”

A warm and cloudless evening on the campus of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. A few hundred students and staffers are spread out on the lawn. The junior senator from Massachusetts strides onto the stage, proclaiming, as she always does, that “we have to make big, systemic change in this country, and I’ve got a plan for that!”

Then, more softly, she tells how a heart attack flattened her father, ended his career as a paint salesman and confined him to softer custodial chores.

“I remember the day we lost our family station wagon,” Elizabeth Ann Warren is saying now.

Donald Trump’s folks negotiated little-guy Queens in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce. Bernie Sanders’s father was a paint salesman, too, but this is not something that his child, busily making revolution for the past 50 years, pauses to discuss. A year from now, one of these three—or Joe Biden—could be elected to the presidency of the United States.

At George Mason, Elizabeth Warren recalls the night that her mother smoothed her best dress on the bed and steeled herself to go to work for the first time in her life. If humility can win the Electoral College, she keeps this in stock too, along with the caws to bring down the Philistines and their oceanside estates.

“We will not lose this house,” the aspirant remembers her mother crying. “We will not lose this house . . . ” On Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, an old oligarch is weeping the same verse.