Hunting for Donald Trump at Camp David

Tight-lipped park rangers, big black Chevys and a Korean war vet next door. What happens at the presidential retreat when Trump’s around?

WASHINGTON, DC – SEPTEMBER 10: (AFP OUT) US President Donald Trump and First Lady Melania Trump walk from Marine One upon arrival on the South Lawn of the White House September 10, 2017 in Washington, DC Trump spent the weekend at Camp David, the Presidential retreat in Maryland. (Photo by Olivier Douliery-Pool/Getty Images)

Share

“Thank you, Mister President, for ruining my weekend,” Sharon the Hiker growled. She was waving her retractable walking sticks in the direction of the Hog Rock Trail, a rough llama-path of logs, leaf litter, and loose gravel that led straight upward from the parking lot to a blank spot on the Maryland map.

“That’s not the trail I wanted to take today,” the Virginian perambulator complained. “That trail is too steep for me. I wanted to take an easier one, but no—not with the president of the United States up there. They’ve closed down half the park!”

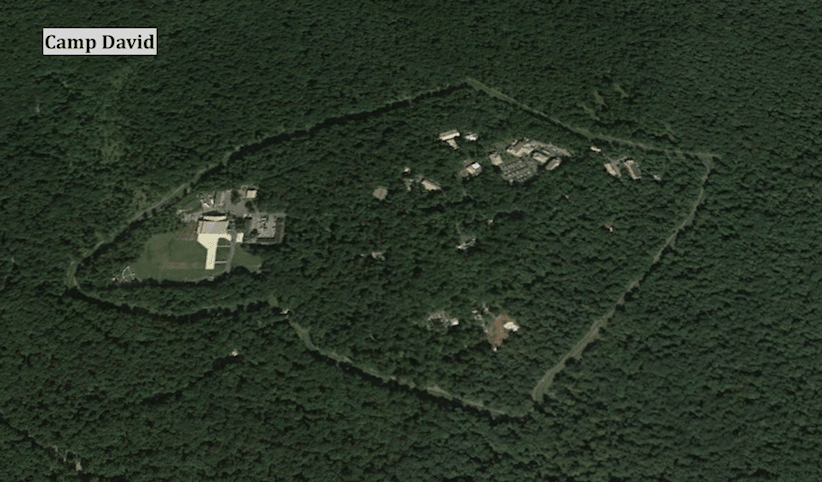

It was true. Donald Trump—along with his entire hand-picked and loyal cabinet—were bivouacked just a few hundred metres to the north of the Hog Rock trailhead, passing a sycophantic sleepover weekend in the Appalachian hills at Camp David, the famous presidential retreat, with its rustic cabins and private target-shooting range.

No press access to their parley was permitted, even as Hurricane Irma bore down on Florida, so a correspondent had to clamber over hill and dale just to get within buckshot of the place. Away from the Visitor Center, leafy park roads were barricaded by humourless musclemen in ear-worms and aviators, while convoys of bulletproof Suburbans with blacked-out windows careered menacingly around the hairpin curves. (Photos supplied by the White House showed Trump and his minions arranged around a table in the Laurel Lodge, looking appropriately concerned. Only The Donald was wearing a necktie on vacation.)

The executive getaway, founded in the 1930s by Franklin Roosevelt—he called it “Shangri-La”—and later named for Dwight Eisenhower’s grandson, is surrounded by the second-growth luxuriance and craggy outcrops of Catoctin Mountain Park, an hour’s drive north of the capital. This is where Jimmy Carter made peace between Israel and Egypt, and where Barack Obama was photographed in the flagrant act of skeet-shooting to stifle those critics who derided him as an effeminate, arugula-eating enemy of the Second Amendment.

Even Vladimir Putin has slept here, if Putin sleeps at all. Yet Camp David has received only a handful of overnight visits from the 45th president, who may well abjure its simple comforts as a rickety, rough-hewn Mar-A-Lego.

Like the geysers of Yellowstone, the cliffs of Yosemite, and the Statue of Liberty, Camp David is embedded within a unit of the National Park Service, whose employees are forbidden to acknowledge that it exists. “We’re not allowed to tell you it’s here, not allowed to tell you where it is, not allowed to tell you who’s here and who isn’t,” a ranger in the Visitor Center shrugged.

“But it’s on every Google map on everybody’s phone,” she was informed. “Just search ‘Camp David,’ and there it is, right in the middle of the park. And every news report in the world says that Trump is hosting his cabinet here this weekend.”

“We’re not allowed to tell you it’s here, not allowed to tell you where it is, not allowed to tell you who’s here and who isn’t,” the ranger persevered.

“If Trump invited you to lunch, what would you say to him?” Sharon was asked, outside the dis-information shack. (One envisioned the First Lady, frying trout freshly caught by Dr. Ben Carson in a cast-iron pan over a Coleman stove, in Jimmy Choo stilettos.)

The hiker, who didn’t want to give her surname, claimed to be a truly independent voter and thinker who had favoured both Republican and Democratic candidates in the past. “If I really got invited to lunch with Trump?” she reacted. “I’d tell him that if he wants his name to be remembered, it’s not enough to have rallies that will be forgotten in a few days, and it’s not enough to sell a lot of hats that say ‘Make America Great Again.’ If he would actually formulate policies that respect the law, if he would actually try to govern and not just go on an ego trip, then he would be remembered.

“Just having a half-assed way of jumping on a different bandwagon every day isn’t a legacy, it’s a sound bite.”

“Is there anyone in the cabinet whom you like?” a reporter wondered.

“I believe that General Kelly must be a true patriot,” Sharon said, naming Trump’s new, no-nonsense Chief of Staff. “He must sincerely want to serve his country, because no one else in his right mind would want that job.”

Across the road, a plinth had been erected above a bubbling little watercourse by The Brotherhood of the Jungle Cock, which is a national organization of fly-fishing aficionados. “Holding that moral law transcends the legal statutes, always beyond the needs of any one man,” it read, “and holding that example alone is the one certain teacher, we pledge always to conduct ourselves in such fashion on the stream as to make safe for others the heritage which is ours and theirs.”

On Catoctin Mountain, that heritage, now a seeming hostage to one man’s needs and tantrums, once belonged to families as rugged as the land. Their farms still waved with corn and beans, just outside the national park boundaries, and above one of them there flapped a Confederate flag.

“When they made them take it down in South Carolina, I decided to put it up right here,” the banner’s owner said. He was a welcoming soul named Edwin Brown, standing in his front yard with a God’s-eye view of the summer hills and the turkey vultures riding the thermals above them.

“It’s history,” Brown said, and he mused that he himself might be related to John Brown, the abolitionist who stormed the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in 1859, hoping to incite an armed rebellion by Virginia’s and Maryland’s slaves. “So many young men died for that flag, fighting for something they believed in at the time.”

The latter-day Brown, a retired truck and snowplow driver for the state department of highways, was no right-wing radical, he swore, and there were no Johhny Rebs on his family tree; it was the blood of those soldiers he wanted to honour. His U.S. flag flew on the same staff, but higher, borne on the identical breeze.

“Top of the hill, second tree on the right,” said Edwin Brown, looking eastward. “That’s where the helicopters go into Camp David.”

As Brown and a visitor stood together, two big black Chevys came barreling down Foxville Road. “A few days ago,” the landowner said, “one of them stopped and a fellow got out and started taking pictures. My wife said, ‘He’s taking pictures of our house,’ but he wasn’t. He was only taking pictures of that flag.”

Edwin Brown’s next-door neighbor was a man named Albert Smith, who will celebrate his 89th birthday on Monday, Sept. 11. Sixty-six years ago, Mr. Smith was taking part in the United Nations “police action” in Korea when a Red Chinese machine-gun bullet knocked his helmet off. Donald J. Trump was a five-year-old in Queens.

“One inch lower and I’d be dead,” said Albert Smith.

Like Edwin Brown, Albert Smith had lived his entire life in the Catoctin hills, but he never had met a president, never had been invited to tea with FDR or JFK or LBJ or BHO or DJT. He had been to Korea, sure enough, but never to Washington, D.C.

“Nothing there I’d want to see,” Smith said. “And nothing there that I can do anything about.”

After his military service, Albert Smith worked at a shoe factory in the little town of Thurmont, Maryland, but that closed in the 1990s and all the cobblers’ jobs went to the Chinese. He was equivocal about the current president, having seen a dozen of them come and go right in front of his house. “Trump says he’ll cut taxes,” he stated, “but he’ll probably raise them instead.”

“Are you ready to go back to Korea?” the 9/11 boy was asked. He had seen smoke and flames on his birthday, and he had seen his life flash before him in combat in the snow. Now the man who will or will not send the next Browns and Smiths to war was roughing it just over the ridge.

“I don’t think they’d take me,” the old soldier replied. “I wouldn’t make it up the first hill.”