Why we can’t stop talking about Hillary’s hair—even with Trump around

Anne Kingston on why hair is the perfect barometer of the pressing issues in the current U.S. election

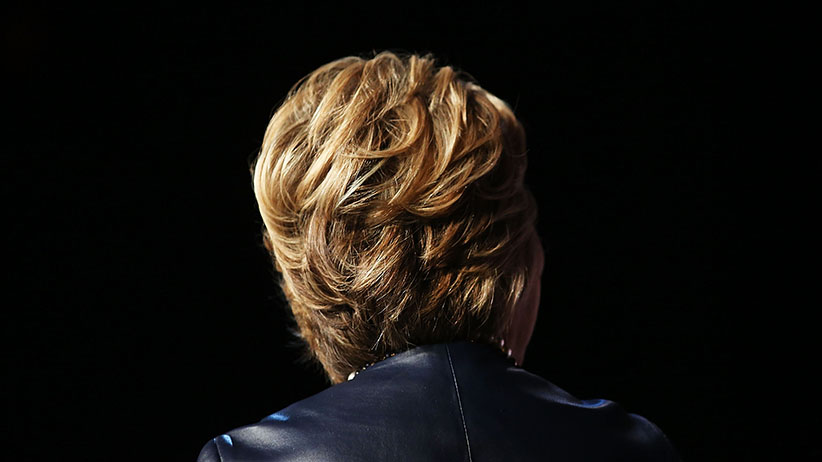

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton speaks on stage in Harlem at the Apollo Theater on March 30, 2016 in New York City. In a new ad released Wednesday by Clinton, she takes on Republican front-runner Donald Trump. New York will hold its primaries on April 19. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Share

Last week Hillary Clinton got a haircut. It made headlines in Republican-friendly publications, including the New York Post. This is not surprising. Hair has become a symbolic battleground in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, be it unrelenting scrutiny of Clinton’s coif, Bernie Sanders’s lack of proximity to a hair brush reinforcing his counter-culture cred and bemused dissection of Donald Trump’s cumulus comb-over echoing both the wonder and disgust over the statements coming out of his mouth.

Certainly Clinton fed this beast by visiting the John Barrett Salon in New York City, known for charging $600 for a trim, another $600 for colour. Yet, while astronomical, those prices are actually not out of whack with the cost of Democratic politicians’ grooming. In 1993, Bill Clinton sparked “Hairgate” by receiving a $200 haircut on Air Force One that brought traffic at LAX to a standstill. In 2007, presidential hopeful John Edwards was slammed for his $300-$500 haircut habit, one decidedly at odds with his cultivated image as an anti-poverty crusader.

Of course, the stakes are far higher for Hillary Clinton, a woman whose hair choices have been microscopically examined for decades. (“Hillary’s hair bands: “Zippy or just dippy?” USA Today pondered during the 1992 election, before fretting about a “disturbing” possibility: “If Clinton wins, headstrong [sic] bands will be the next first-lady fashion trend.” There was outright furor in 2010 when the then-U.S. Secretary of State showed up at the UN General Assembly with a silver butterfly hair clip; the girlish accessory lacked “gravitas,” a Forbes‘ columnist griped.) Now Clinton critics are framing her new “feathered hairdo”—which reportedly required four cars blocking traffic and an entourage, plus putting the fancy department store Bergdorf Goodman “on lockdown”—as telling of a bigger Hillary problems: that she’s entitled, elitist, an establishment player.

Hillary’s hair is a perfect barometer of the case against her at any given moment. Late last year, Matt Drudge, of the Drudge Report, stoked a mini-scandal when he accused Clinton of wearing a wig in a series of tweets that went viral—a perfect metaphor for the prevailing allegation that she’s not “authentic” enough. “Human or synthetic?” Drudge asked. His evidence? He couldn’t see her scalp. The headline of his blog post, “Wigged out: Hillary gives up hair battle” delivered another coded female putdown: that she’s irrational, crazy even. That Drudge, known for breaking the 1998 Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, is now focusing on Hillary’s hair isn’t surprising. As a 2007 Princeton study reveals, surface trumps substance among the electorate; it found 70 per cent of political races could be predicted simply by showing voters photos of two candidates.

When running for U.S. president (and, increasingly, Canadian PM), hair matters. Over the past half-century, the Oval Office has been home to only one bald president—Gerald Ford, who, tellingly, was never elected. He was appointed to top office in 1974 after Richard Nixon’s disgrace, and soon after lost it to Jimmy Carter. The last president to be thin on top was Eisenhower, president between 1953 and 1961. He was followed by John F. Kennedy, a politician who was famously well-endowed, follically speaking. A thick, youthful, authentic head of hair has become synonymous with Samson-like strength and political competence. Clinton, who has admitted to colouring her hair for years, like Ronald Reagan, is keenly aware of this: she’s said there’s no way she would allow her hair to turn white in the White House.

Taking potshots at political hair is destined to summon coverage, seen recently when Clinton, who has protested media obsession over her own hair, took a jab at Trump at a fundraiser: “I feel like we are watching an id — an id with hair,” she said as the crowd cheered. In such a climate, attacks on hair are taken as seriously as those on personal integrity if not more so. In fact, we’re actually witnessing the defence of “hair integrity.” After Drudge attempted to smear Clinton for wearing a wig, one of her hairstylists, Santa Nikkels, who runs a salon in Chappaqua, N.Y., sprang to her client’s defence in People where she reported Clinton had “the most amazing hair in the world.” (Nikkel’s importance to Clinton was evident in last year’s FBI probe into Clinton’s emails, which included several mentions of the former Secretary of State meeting with “Santa”; it, in turn, sparked wild speculation that the name was code for some bigwig the Clinton camp was trying to protect.)

Of course, it’s a feat anybody’s still bothering with Clinton’s hair, given the presence in these primaries of the man dubbed Hair Hitler. Arguably, Trump’s strawberry-blond pompadour, a cantilevered hair soufflé of sorts, has received almost as much attention—and more ridicule—than Clinton’s hair. Even the very serious allegations made by Trump’s ex-wife Ivana in a deposition during their 1990s divorce—that Trump had “raped” her, a version she later modified—went back to hair; Ivana said he was furious about a botched scalp-reduction surgery. Trump denied the rape allegation—and of course that he’d had scalp-reduction surgery.

Trump’s hair exists as a metaphor for the man himself, defying logic, gravity, even description. “A Kangol hat made out of spun sugar,” one hairdresser offered, before providing the more technical description: “Nothing more than an aggressive cowlick with a forward-aiming growth pattern.” Yet the scrutiny of Trump hair, which includes this illustrated history, is different than that aimed at Clinton—it’s less personal, even affectionate. Clearly the billionaire must have a team of hair wranglers; we just don’t know who they are—or what they charge. Where Clinton’s hair summons moral judgments, Trump’s hair is a source of amusement that humanizes him.

While Trump seems unperturbed by the hair jokes and memes he’s inspired, it’s telling how he has aggressively countered allegations that he’s actually bald. Last year, Gawker posted a video to support its claim that the billionaire is “hairless as a naked mole rat” and that what people see is “meticulously crafted bulls–t.” Trump’s 2014 ALS ice-bucket challenge managed to twin Trump-branding with proving his hair is real: Miss Universe and Miss USA, winners of then-Trump-owned beauty pageants, poured Trump-brand bottled water over his head atop Trump Tower. The topic clearly remains a sensitive one: last summer he asked a supporter to come on stage during a rally and give his hair a tug.

Meanwhile, the Sanders camp has chosen to rise about the hair fray. “He doesn’t think his hair is pertinent news to Americans,” Sanders’ press secretary said last year. The candidate is correct. It shouldn’t be. But there’s also no question Sanders’s disdain for hair-combing also works in his favour by reinforcing his image as an anti-materialist too busy fomenting revolution to indulge in the grooming habits of the bourgeoisie. Of course, any equally left-leaning female candidate who showed up with a mad-genius-professor situation overhead would not only be toast politically, she’d be steered toward psychiatric assessment. President Obama said as much earlier this year when identifying the coiffure double standard Clinton faced during the 2008 election, during which it was unearthed that the Clinton campaign paid $2,500 for two hairstyling sessions filed as “media production expenses.” Clinton “had a tougher job throughout that primary than I did,” Obama said. “She had to do everything that I had to do, except, like Ginger Rogers, backwards in heels. She had to wake up earlier than I did because she had to get her hair done.” Now Clinton’s not alone, as a nation focuses on what’s on top, not what lies beneath.