Why scientific information is the key to democracy

Opinion: Recent public-policy failures in Flint and Puerto Rico are related to a lack of openness around public access to information

A man rides his bicycle through a damaged road in Toa Alta, west of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on September 24, 2017 following the passage of Hurricane Maria. (Ricardo Arduengo/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

Scott McKenzie, PhD Candidate, Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES), University of British Columbia

Recently, high ranking officials from President Donald Trump’s government gave the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) a selection of common words it was forbidden from using in draft budget requests.

The now well-circulated list included “diversity,” “evidence-based” and “science-based.”

Fighting infectious diseases is a difficult task but hindering the ability of organizations like the CDC to explain their core functions does a disservice to us all.

But this is far from an isolated incident.

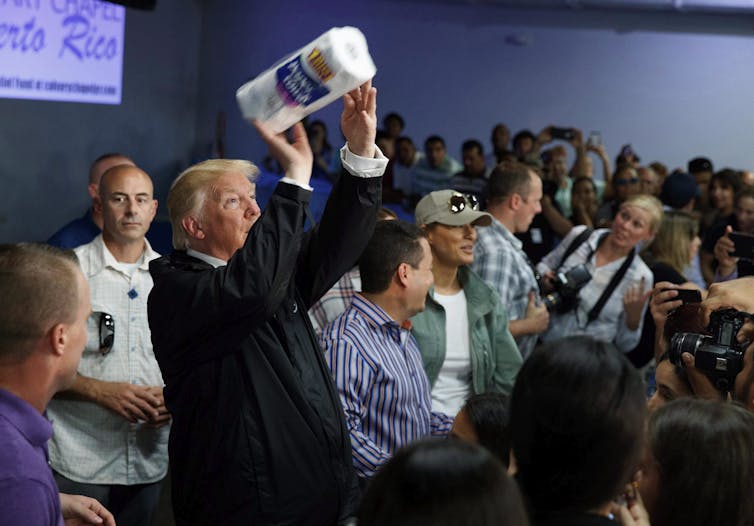

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency deleted key statistics on its web page about the percentage of Puerto Ricans who were living without drinking water and electricity, along with other key measurements of recovery.

This made it difficult to judge the effectiveness of recovery efforts, even if the numbers were later restored. Three weeks after the storm, 35 per cent of residents did not have access to safe drinking water and some were even drinking water from toxic Superfund sites.

Now, the territory is reexamining the number of reported deaths due to Hurricane Maria, and suggesting that the official numbers need to be revised — 10 times as many people may have died.

These events highlight the Trump administration’s hostility towards science — and its fight against the public’s right to scientific information.

We need all the tools we can get to address the environmental and economic inequality felt by many across the globe. Knowledge is a key missing component.

Democracy depends on citizens having knowledge and being a part of the environmental decision making process — being shut out results in growing gaps between those who are protected and those who are not.

The key to public participation

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld is well known for his description of known knowns, the “things we know we know,” and the unknown unknowns, “the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

This second part is the realm of science. Exploring, searching, finding. But, as we saw numerous times in 2017, today we struggle to keep the catalogue of what we do know.

These are the details the public needs so that it can be engaged and informed, take part in the decision-making process and be able to shift its collective focus and energy to where it is needed most. This information is critical to holding all elected officials — from small town mayor to prime minister or president — accountable, a key point in a democracy.

The public’s rights to knowledge and to participate in the environmental decision-making process are outlined by the Aarhus Convention. Although neither the U.S. nor Canada are signatories to the convention, former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan said its “significance … is global… the most ambitious venture in the area of environmental democracy.” States have a requirement to collect and disseminate facts “important in framing major environmental policy proposals.”

The value of an informed public

Only when the public is made aware of environmental information, can it act.

We saw that in the 1970s when concern about the growing ozone hole and its link to an increased risk of skin cancer stirred public opinion and resulted in the groundbreaking Montreal Protocol, the international treaty that phases out the production of substances that deplete the ozone layer.

And we saw it in Canada when the longform census was cut by the Harper administration and vast areas of the country were unaccounted for. This vital information was no longer available to anyone, including the community groups and businesses that depend on reliable information to plan their approaches to addressing our key problems.

Knowledge increases accountability

Knowing the environmental facts is also key to holding our public officials accountable.

The drinking water situation in Puerto Rico echoes the story line from Flint, Mich. There, the public was shut out of the city’s money-saving decision to change the source of its drinking water.

The move resulted in a massive public health crisis that continues to unfold. More than year later, the residents of Flint still deal with contaminated water. Five people connected to the decision have been charged with involuntary manslaughter.

In both Flint and Puerto Rico, public policy failures were related to a lack of openness around public access to information. How can policy be evaluated in the absence of scientific fact?

As my own fieldwork in South Africa has shown, when members of the public have trouble accessing scientific information and the public participation process they can resort to the legal system. However, laws that support the public’s right are essential.

Our future — climate change and science

In the future, our response to climate change will be critical in determining what happens to the world’s most vulnerable people. Until recently, climate change mitigation has mainly been discussed on the global stage, but soon it will shift from being an international issue to one that affects communities large and small.

The impacts of climate change are numerous, and will increase inequality in many ways. Destabilized economies will shed low-skill jobs, rising sea levels will force many to move, and longer bouts of severe heat will create more demand for air conditioning, which will stress electricity grids, add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and release more heat to the environment.

These outcomes are more easily weathered by well-off individuals and families, but could prove disastrous to those living on lower incomes.

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, the U.S. administration began neutering references to the well-documented impacts of climate change. These actions were opposed by many cities, including Chicago.

“The Trump administration can attempt to erase decades of work from scientists and federal employees on the reality of climate change, but burying your head in the sand doesn’t erase the problem,” Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel said at the time.

![]() Science can help the public address an uncertain future. Only a policy of openness will ensure a shared commitment of equality for everyone.

Science can help the public address an uncertain future. Only a policy of openness will ensure a shared commitment of equality for everyone.

This piece was first published at ![]()

![]()