Why sudden NAFTA progress is thanks to the U.S.-China trade war

America doesn’t have the resources to fight China and its North American friends on trade at the same time. Something has to give.

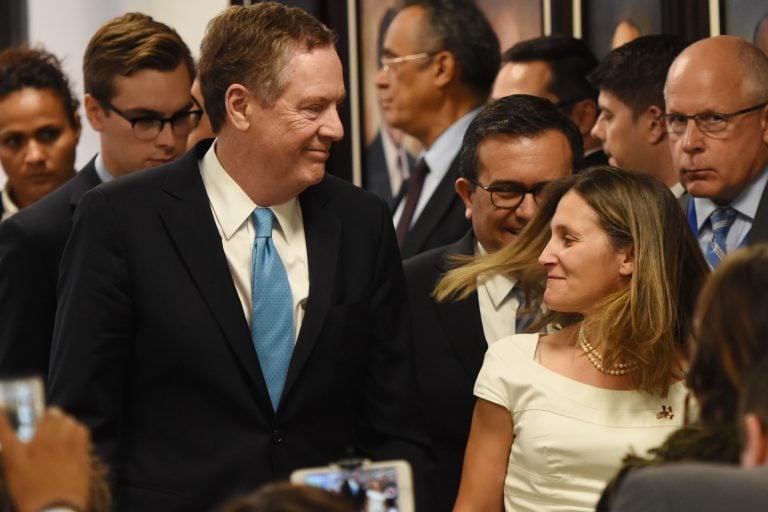

Chrystia Freeland, and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer at the finish of a press conference at the Second Round of NAFTA Negotiations on Sept. 5, 2017 in Mexico City, Mexico (Photo by Carlos Tischler/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Share

Slowly and unsurely the NAFTA negotiations went—until Friday afternoon, when Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland met with American trade negotiator Robert Lighthizer and their Mexican peers in Washington. “The bottom line is we had two days of intensive and constructive and productive work,” Freeland said. “We’ve entered a new, more intensive stage of engagement.”

It was America’s global trade war talking.

“This is U.S.-China relations in capital letters that is in the background,” says Paul Evans, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. “We may be into a possibility of a little safer NAFTA harbour, but the storm in the ocean out there is the bigger picture.”

North America could be on the cusp of restoring its trade deal, with U.S. President Donald Trump saying on Thursday, “we’re working very hard on NAFTA with Mexico and Canada. We’ll have something, I think, fairly soon.”

But fairly certainly, after three seasons of unproductive negotiations, this progress is less a result of shrewd bargaining than a symptom of Trump’s fight with Beijing, which suddenly pressures the U.S. Trade Representative to get NAFTA out of the way. Trump has threatened China with $100 billion in tariffs, and China has responded with threats of its own, raising the possibility of an unprecedented, far-reaching trade war.

If the U.S. signs NAFTA for the sake of frying bigger foreign fish, Canadians must beware this could only be a short-term win. “When we see the United States using the 301 instrument against China,” says Evans, “it brings shudders to the spine of Canadian negotiators with the United States.” Evans is referring to Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which Trump employed in 2017 to investigate China for theft of American intellectual property. The results showed billions of dollars of losses and led Trump to say he wanted a $100 billion reduction in trade with China (in early March, he tweeted that he wanted a “$1 billion” reduction, but his spokesperson said it was a typo).

READ MORE: Brian Mulroney: Anyone expressing fear and anger over NAFTA is ‘uninformed’

“They brought out the heavy artillery against China,” Evans says, “and while it’s not aimed at Canada right now, and we may be at a moment of some tactical advantage, in the longer term, that willingness to bring out 301s in that kind of way makes all of us shudder.”

The USTR could feel added pressure to free up their staff from North American trade talks because the department has been reportedly understaffed since Trump came to office. Amid negotiating rounds this fall, a source close to the talks told Maclean’s, “there’s just not enough folks in there.”

“I would agree that the imbroglio between the U.S. and China have helped the NAFTA negotiations,” says Lawrence Herman, a former diplomat and lawyer at Herman & Associates in Toronto. “The Trump administration has to deal with a serious battle, if not a war, with China and deploy as many resources as they can possibly deploy on dealing with that particular issue.”

That particular issue results from Trump’s geopolitical agenda outlined in the 2018 National Defence Strategy, which portrayed China (and Russia) as competing with the U.S. in diplomacy, economy and security. “It’s not called an ‘enemy,’ but it’s called a ‘strategic competitor,'” Evans notes.

Given its actions on China, there’s no telling now what America could be prepared to do to Canada in the future. Even if it signs a NAFTA deal, it shouldn’t be called a “friend.”