Donald Trump is starting a trade war. Here’s why it will go dangerously wrong.

The consequences of the president’s enthusiasm for economic conflict could be widespread and severe. In trade wars, no one wins.

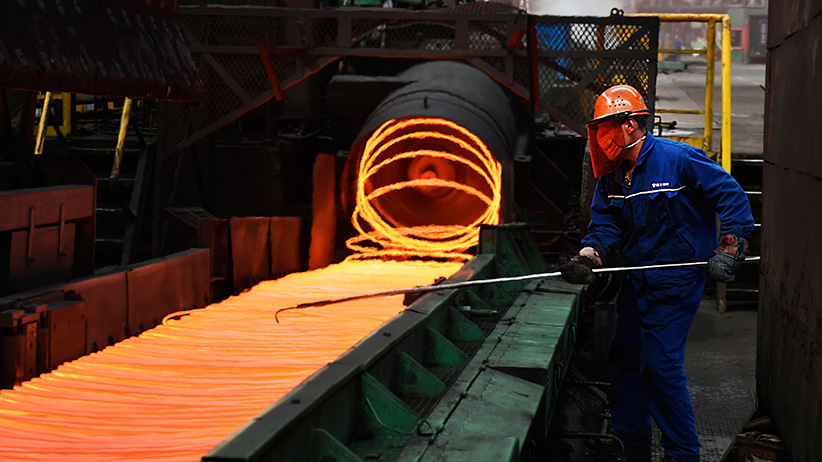

U.S. President Donald Trump delivers remarks before signing the ‘Section 232 Proclamations’ on steel and aluminum imports. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Share

If Edwin Starr were to re-work his most iconic number with current events in mind, it would begin, “Trade war, huh, yeah, who is it good for? Absolutely no one.”

But Donald Trump disagrees. The president today signed orders imposing tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum. He’d provided advance notice of the new duties in the form of tweets, including one that took a sunny view of trade wars:

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 2, 2018

Trading partners of the U.S. have signalled that they could respond in kind, with duties and tariffs on American exports. The result could be an escalation of the conflict, leading to price increases and job losses.

Observers and economists are keen to stress that the worst-case scenarios are unlikely to play out. Elements within the president’s own administration and party have reportedly been working to convince Trump not to go down this path, and corporate interests have also aligned against the new duties.

Even with the tariffs implemented, all of what happens next depends on the specific wording, the action that other countries and companies take in response, and the length of time that these measures unfold over. “I don’t actually think this is going to lead to a full-on [trade] war,” says Mark Warner, an international trade lawyer and principal at Toronto’s MAAW Law.

Trump is hardly the only world leader today who believes globalization and free trade have more cons and pros. But his explicit enthusiasm for economic conflict is unusual—and misplaced, say experts. Trade wars ultimately hurt the economies of the countries involved and consumers. It starts with retaliation.

Retaliation

Canada has been granted a temporary exemption to the new steel and aluminium tariffs. But the president has tied the issue to the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation, in which the U.S. is making demands that are are unacceptable to Canada, says Craig Alexander, senior vice-president and chief economist at the Conference Board of Canada. “If you think the tariffs are a bullying tactic, do you stand up to the bully, or do you let it go?” he asks.

History suggests it’s hard for a Canadian leader to ignore aggressive trade action from the U.S. When the U.S. imposed protectionist policies known as the Smoot–Hawley tariffs in 1930, William Lyon Mackenzie King was seen as being insufficiently tough. That perception helped sink him and make R.B. Bennett prime minister.

Trudeau faces a similar problem. “Even though he might not want to retaliate, in a way he has to,” says Judith McDonald, a professor of economics at Lehigh University, who has studied the Canadian reaction to Smoot-Hawley.

The European Union was the most strident in its response to the initial news of Trump’s tariffs. “We can also do stupid,” European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker told a German TV channel. He picked out Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Kentucky bourbon and Levi’s jeans as particular targets, which an official told the New York Times were “just examples,” and a full list of products was in place.

Still, there’s logic to those choices. “You have to put it on something that will get their attention,” says Warner. U.S. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell is from Kentucky, for example. “The idea that his constituents will say, ‘McConnell, fix that.’ ”

Harley-Davidson hails from House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan’s home state of Wisconsin. India recently cut its duties on high-end motorcycles, something Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted to the president in a recent call, though Trump was dismissive of the gesture.

The level of economic integration across the 49th parallel leaves no easy targets, and Canada has historically shied away from retaliatory measures because of the potential domestic damage. In a 2015 dispute over meat imports, “Canada spent a fair amount of time putting together a very strategic list of products” to levy duties on, says Laura Dawson, director of the Canada Institute at the Wilson Center. California wine and Washington apples were both targets, though the issue was resolved before retaliatory tariffs were imposed.

The domestic problem

Politicians attracted to protectionism are banking on the idea that restricting imports will help boost domestic industry, Alexander says. But while some sectors might see additional investment, many businesses will do the opposite, scaling back because of now-higher input costs, causing them to hire fewer new people.

It’s a basic misunderstanding of the effects of free—or at least freer—trade. Take the example of a Proctor & Gamble plant in southwestern Ontario. Pre-NAFTA, the facility had been turning out 10 different items in short production runs for the Canadian market. After the deal, it shifted to making just two, but in much greater numbers because it was for all of North America. “Costs went down, employment went up, and everybody was happy,” said Walid Hejazi, an associate professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, speaking last year when Trump was threatening to withdraw from NAFTA altogether. “All of those gains would be lost” in the absence of free trade.

RELATED: Donald Trump is making America more expensive for consumers

The stock markets have already been moving on fears of interest rate increases because of inflation due to rising costs, McDonald points out. In the short term, tariffs reduce supply or make it more expensive. “Let’s say they have a dormant steel mill and they want to get it producing again—that’s going to take time,” she says. In the meantime, U.S. manufacturers and other firms will have to pay more for imported metal, creating an inflationary effect.

Consumers will also be hit in the wallet, because companies will pass some or all of their increased expenses in the form of price increases, or simply stop offering products if the tariffs become prohibitive. “Ultimately that leads to slower economic growth and worse outcomes for people,” says Alexander.

Escalation

Unchecked, opposing sides in a trade war could come to resemble two grade schoolers alternately crying, “No, you started it.”

A vicious cycle could be trigged if countries respond to the U.S. action with tariffs of their own, and the U.S. then imposes fresh levies on further goods.

Governments responding to what they see as unfair tariffs typically “try to make their response focused and proportionate,” says Dawson, because they’re trying to minimize the economic damage while still sending a strong message. It’s not the size of any one retaliatory tariff, but the number of duties levied back and forth that causes the escalation. “If you’ve got multiple countries and multiple sectors all over the world doing this, you can’t help but get a fairly chaotic effect,” Dawson says.

The U.S. would of course be the focus of retaliatory action. But “when you disrupt any node on a global supply chain, it has ramifications all over the world,” Dawson notes.

The U.S. investigation that preceded Trump’s tariffs does provide Canada with an escape route, but taking it could have consequences. The unions and companies petitioning the administration in that process allowed for an exemption if action was taken against circumvention—the exporting by other countries of steel and aluminium into Canada so that it can then be exported to the United States under the maple leaf flag. Major sources of imports to Canada include South Korea, Taiwan and China. But tightening our own import regime would not come without cost. “The price for getting out from under the U.S. order may well be agreeing to do things that piss off some of our Asian exporters,” Warner says.

‘Mutually assured destruction’

There’s another landmine hidden in this unfolding battle, and that’s the framing of Trump’s actions in terms of national security. It’s using a provision commonly known as Section 232, which stems from a 1960s-era U.S. law. “It stands outside of the WTO system,” says Warner.

Warner says the U.S. has only threatened to invoke this particular rationale within the framework of the WTO and its predecessors three times, with the last two coming in cases of economic sanctions or embargoes of Latin American nations. None of those cases were ever acted on, though, Warner says, because “this is kind of like mutually assured destruction.”

Any challenge within the WTO system to the U.S. action by another country would take a long time to reach a final verdict—years, between the initial ruling, appeals and compliance bodies.

Historically, the U.S. position has been that national security rationale is “self-judging,” meaning once it’s invoked, there is no recourse against it. If a trade dispute panel were to rule on that issue, it could have serious consequences either way. If the decision went against the U.S., the fear is that the country “would just, pretty much under any president, say, ‘bye bye’ to the WTO,” Warner says. But if the WTO were to uphold the U.S. position, it would provide a licence for every other member to cite national security as justification for any protectionist measures.

Warner calls this a “neutron bomb” scenario.

The fundamental flaw

Alexander says the president’s comments on tariffs and trade wars display the basic flaw in his thinking. “Trump views trade as a zero-sum game,” he says, but in reality the concessions that both sides make actually lead to greater shared prosperity.

The specific outcome Trump is seeking, the restoration of manufacturing and blue-collar jobs, will not be achieved through the measures he’s taking. “A lot of the disruption in the labour market hasn’t been because of trade, it’s been because of technology,” says Alexander.

That faulty logic applies in the case of the current tariffs, too. “If you’re going to get an old steel mill running again, aren’t you going to use the latest technology?” asks McDonald. That means robots and automation, not a huge number of new jobs for metalworkers.

Figuring out exactly how all of this will play out is difficult, because it’s never happened quite this way before. “It’s like the butterfly effect: How much can a single action in one part of the world affect global trade?” says Dawson.

But what is clear is that Trump’s assertion that “trade wars are good, and easy to win” is exactly backwards, says Alexander. “In point of fact, trade wars are bad, and no one wins.”