Prince William’s Middle East trip is the future king’s biggest test

Prince William’s Middle East tour, which includes the first official visit to Israel by a senior British royal, will be fraught—and it’s unclear if he’s up for the challenge

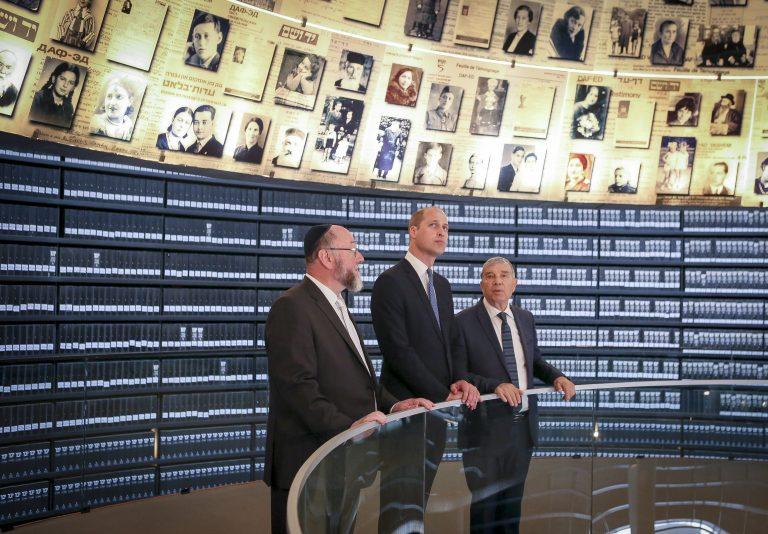

Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, visits the Hall of Names with the UK’s Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis (left) at Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial and Museum during his official tour of Jordan, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories on June 26, 2018 in Jerusalem, Israel. (Ian Vogler/Pool/Getty Images)

Share

For two days, Prince William’s trip to the Middle East was a cakewalk. It began in Jordan, where he was hosted by Crown Prince Hussein, whose father King Abdullah II was in Washington to meet with President Donald Trump to talk about the myriad problems afflicting his small nation. It was relaxed and oriented around youth, a specialty for William, and formality—something William endures with limited patience—was at a minimum; the two future monarchs went to Fablab, an initiative of Hussein’s that equips entrepreneurs with needed technology, and also met with some of the hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees who have sought asylum in the country. The pair even camped out in the royal family’s private residence to watch England defeat Panama 6-1 at the World Cup.

That was the easy part. The Jordan leg was just the start of Prince William’s high-profile five-day trip to the Middle East, which will include the first official visit by a senior member of the House of Windsor to Israel—and one that may make or break the reputation of the British monarchy’s future king.

The Duke of Cambridge has arrived in Israel for the first official visit by a senior member of The Royal Family. pic.twitter.com/gBHbjjqhfG

— The Royal Family (@RoyalFamily) June 25, 2018

The 36-year-old has never undertaken a trip to such a volatile area, and the Middle East is layered with enough political, cultural and historical pitfalls to trip up even the most experienced diplomat—and to this point, William has relied more on his easy charisma than his prep books. The stakes, too, are increasingly high. His grandmother Queen Elizabeth II, whose workload continues to be significant, is now 92, and so his performance is being carefully watched by palace officials who need William to step up the pace of his royal duties both in Britain and abroad.

While the events in Jordan played to William’s strengths, the more formal agenda in Israeli and the occupied Palestinian Territories is where the trip’s success or failure will be decided. Well after the visit ends, every word and gesture will be analyzed for the slightest hint that he’s taking sides in the region’s fraught politics. Though it’s been billed as an apolitical trip—“There is no political message, the duke is not a political figure,” emphasized David Quarrey, Britain’s ambassador to Israel, ahead of the visit—being involved in the region’s complicated relationships is all but unavoidable.

It’s already begun. Before the trip even started, Israel caught wind of the fact that William’s itinerary referred to the Mount of Olives and East Jerusalem as “Occupied Palestinian Territory,” as per British government policy, prompting Jerusalem Affairs Minister Ze’ev Elkin to call the name a “distortion” of his government’s belief of a united Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Even the hotel he is staying at, the King David in Jerusalem, is a testy part of the region’s history: In 1946, it was the headquarters of the British Mandate when the Irgun, a militant Jewish organization, bombed it, killing 91 people.

This will not be a tour where William can get by with charm and a quick smile. The three days in Israeli and Occupied Palestinian Territories start with a visit to Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. He’ll meet countless politicians with their own political agendas, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who could use a distraction from his myriad legal problems: his wife Sara was just charged with fraud, while he’s entangled in multiple corruption investigations. He’ll also meet with the elderly, ailing Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, who is facing increasing pressure from a moribund economy and peace process. There will be endless receiving lines where he must make lots of non-committal small talk at lots of diplomatic receptions.

Indeed, Israel’s president Reuven Rivlin asked William during a meeting, “as a prince and a pilgrim,” to “send a message of peace” to the Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas, a reminder that the two sides broke off all talks when the United States moved its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. William avoided a political stumble by being non-committal: “I very much hope that peace in the area can be achieved.”

William’s senior advisor Sir David Manning—who was Britain’s ambassador to Israel—is there to help navigate him through the diplomatic tangle. But unlike previous high-profile trips, the prince’s wife, Kate, stayed home to be with their newborn third child, Louis. Ultimately, then, the responsibility will fall on the prince’s shoulders alone.

But past experience suggests it’s unclear if William will rise to the occasion. Typically, given that nothing on a foreign tour is left up to chance, royals are given briefing books detailing every aspect of the events they’ll undertake, including the purpose of each visit, bios of people they’ll meet, information about the organization or charity, and minute-by-minute accounting of what they will do. Yet talk to royal reporters on a tour about which royals assiduously plow through the research files and who tends to skim the highlights, and William’s name is put in the latter category.

That was on display in Vancouver during the duke and duchess of Cambridge’s most recent Canadian tour. Everyone who’d read the itinerary knew the couple’s visit to Sheway House, a pregnancy support centre in the Downtown Eastside, was because it was modelled after one in Glasgow, Scotland, that William’s mother, Diana, princess of Wales, had opened—at least, everyone except William. “Oh, I didn’t know, that’s good to hear,” he said upon being told. “It’s probably in my briefing notes somewhere. I’ve got this huge file of notes I haven’t managed to get through yet but I’ll get there.” Sure enough, that’s what dominated coverage. “Prince William admits he didn’t read briefing papers on Diana link to charity,” was the Daily Express headline.

These questions about whether Prince William wants the responsibilities that go with his position have existed for years. In 2016, he was named a “work-shy petulant prince” when he didn’t undertake his first royal engagement of the year until mid-February. This year, he’d finished just 104 events before flying to Amman, enough to put him in just ninth position among full-time working royals.

More importantly, he has a reputation for being stubborn and resisting staffers who question his decisions. As Ingrid Seward, the editor of Majesty magazine, said two years ago during a PR contretemps involving a luxury vacation: “His aides are very young and very good, but the problem is William has never really taken advice and has a tendency to think he is always right.” He appeared to plunge into the political debate surrounding Brexit by delivering a speech to the Foreign Office that was widely perceived as pro-European just two days before the referendum date was announced.

But the short Middle East tour is the sort of trip William will be expected to undertake several times a year, for decades to come. Its apolitical mix of formal ceremony, charitable efforts and mingling with locals is the royal family’s stock-in-trade. On such tours, he is never fully off-duty. On June 28, he’ll follow in the steps of his grandfather, Prince Philip, and his father, Prince Charles, by visiting the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in East Jerusalem, where his great-grandmother Princess Alice is buried. Prince Philip’s deaf mother hid a Jewish family from the Nazis in her home in occupied Athens during the Second World War and, in 1993, Yad Vashem recognized Princess Alice as Righteous Among the Nations.

The cameras will record every moment for posterity. A few hours after that personal moment, Prince William will leave the Middle East. And the evaluations of how he did will begin.