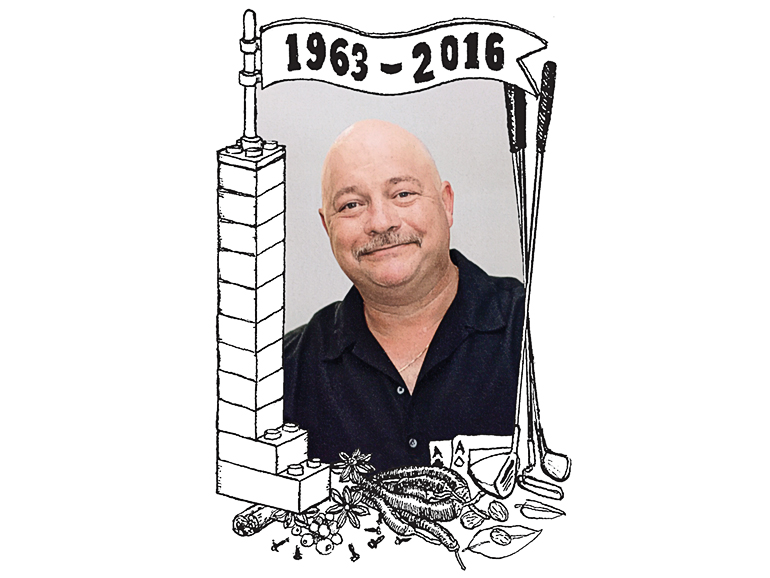

Barry Dean Maitland, 1963-2016

His father’s death transformed him into a diligent, hard worker. A welder by day, he dreamed of running his own food truck.

Share

Barry Dean Maitland was born on April 22, 1963, in Edmonton to Phyllis, a stay-at-home mom, and John, a long-haul trucker. The couple had six kids; four in rapid succession and then, eight years later, twin girls. Sadly, one twin survived less than a day.

Barry Dean Maitland was born on April 22, 1963, in Edmonton to Phyllis, a stay-at-home mom, and John, a long-haul trucker. The couple had six kids; four in rapid succession and then, eight years later, twin girls. Sadly, one twin survived less than a day.

Barry was fourth and proved a handful, says Phyllis. When he was six, she says, “he and one of the little neighbour girls decided they wanted to have a wiener roast over a campfire. So they went and lit a fire on the floor of a house that was under construction.” Fortunately, it didn’t burn down. In his teens Barry frequently snuck out of his bedroom window at night, rounded up buddies, bought beer and found trouble. Tragedy turned Barry’s life around at age 16. His father, who was helping unload heavy equipment off a lowboy trailer, fell 1.5 m off the gooseneck hitch when a board snapped. John, 45, fatally struck his head. Phyllis was left alone at home with Barry and his younger sister, Wanda. Barry, who had already quit high school to get a job, quickly became a more diligent, responsible person.

In August 1983, Barry, then 20, went for a weekend at the family cabin at Long Lake Provincial Park north of Edmonton. Linda Maracco was on the lake paddling a canoe with two girlfriends “when a guy went waterskiing by and sprayed us.” Later that day the girls joined a beach volleyball game. One player, Barry, invited them to his cabin for drinks. “I mentioned some jerk on a boat [had] sprayed us,” says Linda. “Barry starts laughing and says, ‘Yeah, that was me!’ ” Barry gave Linda his phone number and she phoned him as soon as she returned home from the weekend. A month later, at a drive-in movie, Barry asked Linda, an administrative assistant at a brokerage firm, “What would you say if I asked you to marry me?” She said, “Sure.” They married a year later.

Linda got pregnant and discovered after an ultrasound they were having twins. She excitedly called Barry. He joked to her: “No more ultrasounds please, because they are probably going to find another one.” Steven and Jason were born in 1985. A third child, Amanda, came in 1987. Barry, says Linda, was “an awesome dad.” He introduced the kids to Lego. There were cars, spaceships, and military vehicles. “Two of the biggest we did,” recalls Jason, “were a submarine and the USS Kitty Hawk.” The latter, a 1,700-piece aircraft carrier over 1.5 m long, took five days to build. The boys struggled to keep their dad’s paws off the blocks.

In 1985, Barry, then working for a roof truss manufacturer, decided to take a welding course at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology, finishing the four-year program in three. Though welders made good money in the oil patch, Alberta’s boom-bust cycle made for some tough times for the Maitlands. In the late ’90s Barry worked two jobs for three years straight, doing a night shift at one, a day shift at the other. “He’d be home for a grand total of four hours and then be off back to work,” says Jason.

He was working hard, hoping he could retire early. But Barry also had a retirement plan in mind for his kids, says Jason. “He wanted it set up where we could work to our late 30s, then retire ourselves. Maybe have a hobby on the side to bring in a bit of money.”

When he was off the job, Barry loved to golf, cook and play Texas Hold’em with pals. He was also a spice-aholic. He and Linda loved watching Food Network programs together like Cutthroat Kitchen and Top Chef. Barry, who kept a cupboard with a constantly evolving spice collection (smoked paprika was his favorite) loved replicating recipes on those shows. He was known for his own pizza creations, his chicken and pork schnitzels and his slow-cooked ribs made with his own spice rub. He dreamed of operating a food truck, thinking maybe he’d sell donairs or pizzas.

A welder for 29 years, Barry nudged both his boys into similar careers. It could be dangerous work; Barry, for instance, once worked on the 45-m-high water tower at Fort Saskatchewan. But ever since his father’s workplace death, Barry had always been extra cautious about safety, says Linda. “Anyone that knew Barry, he would drill it into their head. He would drill it into our boys.”

On Jan. 18, Barry, working for a fabrication and engineering company, was welding atop a steel tank when he somehow fell nine metres to his death. He was 52.