Be wary of charities that pay their staff too much—or too little

Exclusive analysis shows that charities paying high salaries fare worse on financial and transparency metrics. But low compensation is a warning sign also.

Hand putting Coins in glass jar for giving and donation concept

Share

Eighteen hospital fundraising charities across Canada had at least one employee earning $350,000 or more in 2016. Out of those active today, Toronto’s Michael Garron Hospital Foundation is the smallest to pay someone that much money.

Of the 86,000 charities across the country, only 221 had employees making $350,000 or more. Just 553 people in total earned that level of compensation—and foundation president Mitze Mourinho was one of them. Exact salaries aren’t reported, but Mourinho’s salary accounted for at least 4.7 per cent of the charity’s total revenue of $7.7 million.

Under Mourinho’s leadership, the hospital foundation’s total revenue has since increased to $13 million in 2018 and the organization argues his salary is competitive with other similar organizations in the Toronto area. But Kate Bahen, managing director of the research organization Charity Intelligence, said this level of pay is an example of how charity executive salaries are spiralling upward.

“You get this cycle of out-of-control cost escalation with nothing to do with performance,” Bahen said. “There definitely seems to be runaway compensation at some charities.”

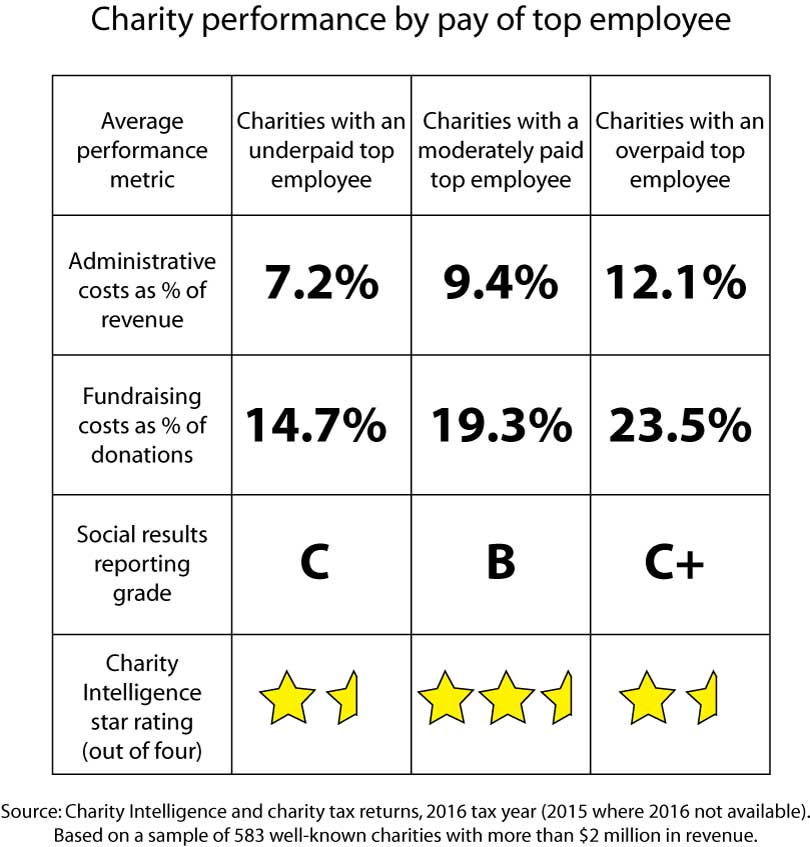

In fact, a Maclean’s analysis of charity data suggests extremely high compensation is linked to poor results for charities. But intriguingly, so is extremely low compensation. Charities that pay their highest-paid employee much more or much less than their peers of a similar size perform worse on a variety of financial and transparency metrics. Last year, Charity Intelligence put out a report calling charity salaries “a useless metric in intelligent giving,” saying the organization had been unable to find any link between compensation and performance. But Bahen said she was re-thinking that stance in light of the Maclean’s analysis.

“I think you’ve got something there,” she said. “Too many smart people have said, ‘Salaries matter.’”

Maclean’s looked at data from almost 600 of Canada’s best-known charities with revenues over $2 million. The analysis found that charities paying their highest-paid worker at least $100,00 more than the average top employee at organizations of a similar size are both less efficient and less transparent.

Charities that overpay their top employees spend more on fundraising and administration, devoting a smaller percentage of their money to accomplishing their charitable goals. They also provide lower-quality communications to donors about how money is being spent and the results of their work. This results in them receiving lower ratings from Charity Intelligence.

The correlation held for charities with operating costs up to $20 million. For organizations that large, high salaries did not appear to be associated with worse performance.

Charities that substantially underpay their employees run into trouble as well. Charities of any size that pay their highest-compensated staff member less than $80,000, or do not have any full-time staff at all, are less likely to have audited financial statements posted online, provide less information to donors about how their money is helping people and also receive lower ratings from Charity Intelligence.

Meredith Ferguson, a spokesperson for the Michael Garron Hospital Foundation, took issue with comparing the charity to others in different sectors and regions.

“We aren’t an outlier when you look at Michael Garron Hospital Foundation geographically,” she said in an email. “The GTA is an incredibly competitive market for executive talent, and of course, salaries are higher in Toronto across the board in all sectors than elsewhere in the country.”

Both salaries and overhead costs tend to be higher at hospital foundations than similar-sized charities in different sectors. Fundraising and administrative costs at the 88 hospital foundations included in the Maclean’s analysis accounted for 27.3 per cent of revenues on average, compared to 19.5 per cent at other charities.

At the Michael Garron Hospital Foundation, fundraising and administrative costs accounted for 30 per cent of revenue in 2018, an improvement from 39 per cent in 2016. Ferguson said the foundation’s fundraising costs are comparable to other similar-sized community hospital foundations in the Greater Toronto Area.

“In large, noisy markets like the GTA where there are approximately $5-billion in capital fundraising campaigns happening in the healthcare sector, market share is a particular challenge for community hospitals – we are competing for donor dollars with huge brands,” said Ferguson. “We attract a smaller share of healthcare fundraising dollars in our area in comparison to community hospital foundations across the country.”

But Bahen, from Charity Intelligence, said hospital foundations have advantages that should make it easier and cheaper to fundraise. They can use lists of former patients to send fundraising appeals, which are more likely to be successful because people are naturally inclined to give back for the services they received, she said.

“Raising money for hospitals should be one of the easiest fundraising jobs,” she said. “Do you really need to be paid that kind of money to shoot fish in a barrel?”

There are many who think donors shouldn’t spend much time worrying about salaries when deciding where to give. Bruce MacDonald, president and chief executive of Imagine Canada, an organization that provides support to charities, suggested interest in compensation is overblown by the press.

“We hear a lot of media who ask about charity salaries,” he said. “But I’ve got to tell you, in the fundraising world, I don’t actually hear a lot of that.”

Greg Thomson, Charity Intelligence’s director of research, said that has certainly not been his experience.

“We speak with donors who really care about salaries all the time,” he said. “Some folks just think it’s wrong, it’s immoral even, for someone working at a charity to get paid very much.”

MacDonald also took issue with the very idea of comparing and ranking charities on financial and transparency metrics across sectors.

“The hard part is to look for absolute rights and absolute wrongs in our business,” MacDonald said. “The cookie-cutter approach to understanding who’s good and who’s bad does not, I believe, accurately reflect the state of each organization.”

Maclean’s analysis suggests that in most cases, the compensation of the highest-paid staff member does not affect performance at charities. The correlation only holds at the extreme ends of the spectrum.

Most charities in Canada are very small and six-figure compensation is relatively rare. Tax return information from 2016, the most recent year available, for the country’s 86,000 registered charities shows they had median total annual expenses of $102,000 per year. Three-quarters of charities have two full-time employees or fewer.

The median top salary for charities with at least one employee is between $40,000 and $79,999. The Canada Revenue Agency requires charities to report a salary range, rather than an exact salary, for their 10 highest-paid employees.

That makes the 221 registered charities paying at least one person in the highest salary bracket of $350,000 or more extreme outliers. Because the bracket has no ceiling, the staff reported in it could be making $350,001 or $3.5 million.

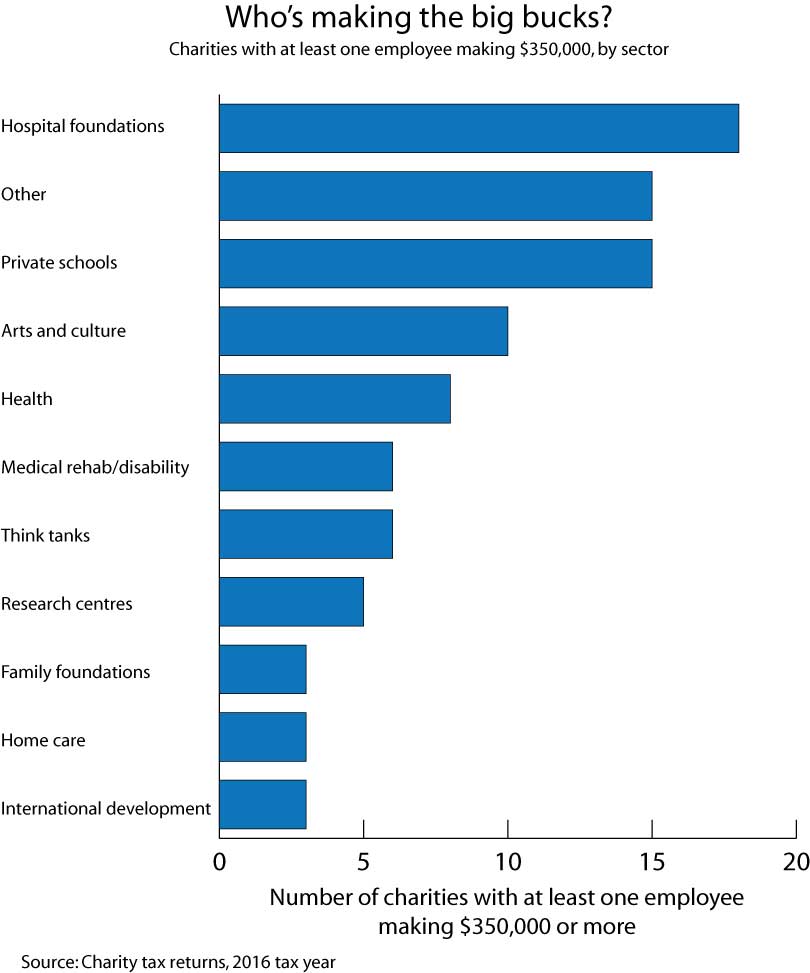

More than half of the 221 registered charities paying at least one person in that top salary bracket are organizations that have charitable registration numbers, but aren’t normally thought of as charities by the public, such as hospitals, governments and public school boards. Excluding those organizations, hospital foundations, private schools, arts and culture charities and health charities were the most likely to pay a staff member $350,000 or more.

Donors can draw their own conclusions about whether these charities’ top salaries are justified, but the list might be missing some members. There are ways a charity can report compensation that keeps it out of the CRA’s publicly available salary bracket schedule.

A donor who looks up Colorectal Cancer Canada in the CRA’s charities listing will see the organization’s total amount spent on compensation listed as $227,000 in 2017. The compensation schedule shows one staff member paid less than $40,000 and three others paid between $40,000 and $79,999.

But that donor would have no way of knowing chief executive Barry Stein, who is also a director, is paid as an independent contractor, with his remuneration filed under “professional and consulting fees” in the tax return. On the last page of Colorectal Cancer Canada’s 2015 financial statements, which are not available on the charity’s website, there’s a note titled “related party transactions,” stating that “the Association paid consulting fees of approximately $264,000 (2014 – $264,000) to a director.”

Stein confirmed he is the director the note is referring to, which means his compensation accounted for more than one-quarter of the charity’s revenue of just over $1 million that year.

Stein said he believed he had “an obligation under the audit rules” to report his remuneration this way and that it was not done with the intention of obfuscating. “There’s nothing to hide. We’re very transparent about what we do,” he said.

Stein also noted the $264,000 payment was a gross amount including taxes, expenses and pay for secretarial staff. He said he believed his compensation was reasonable given his three degrees, legal expertise, clinical knowledge and bilingualism.

“I’m not bragging, here, but I think with the type of expertise I would need, I would need three employees [to replace myself],” he said.

Laws about whether charity directors can receive compensation — as independent contractors or otherwise — vary province to province. Directors have the power to approve compensation, creating a potential conflict of interest.

It’s not clear what jurisdiction Colorectal Cancer Canada falls under, since it has offices in both Ontario and Quebec. Charity lawyer Mark Blumberg said the arrangement is unusual, even if it’s within the rules.

“When your most expensive person is not listed, boy oh boy, does it make your numbers look better,” he said “This is not what I would suggest to charities as a model of how you run things.”

High salaries receive the most attention, but Maclean’s found a stronger correlation with poor performance at charities that underpay their staff or have no staff at all. In particular, large charities that paid their top-compensated employee less than $80,000 had worse social reporting scores, a metric designed by Charity Intelligence that assesses the quality of communications to donors about how their money is being spent and the impact it’s having.

Many donors may like the idea of a large charity with razor-thin overhead margins operating without any paid staff. But Bahen said she considers this a red flag.

“The minute I see a big charity with no staff, we’re just like, ‘What’s going on here?’” Bahen said. Out of eight charities reviewed by Charity Intelligence whose charitable registration was later revoked by the CRA, four had no staff and no salaries.

For example, in 2017 the CRA revoked the charitable status of Vaad Mishmeres Mitzvos Committee to Observe The Torah Laws, a charity that reported $32 million in revenue in 2015 and zero spending on compensation. The tax agency cited a failure to demonstrate the people benefiting from the charity qualified as needy beneficiaries, a failure to maintain adequate records and a failure to file a tax return.

In 2016, the CRA revoked the charitable status of Smile Train Canada, the Canadian arm of the New York City-based charity Smile Train Inc., known for its heart-rending television advertisements featuring children with cleft palates in the developing world. The CRA said Smile Train “lacks direction and control over the use of the Organization’s resources, failed to carry out its own charitable activities, failed to allocate the Organization’s resources towards its own purposes and activities, failed to maintain proper books and records and failed to file an accurate information return.”

Smile Train Canada reported no spending on staff or compensation, despite pulling in more than $2.5 million in revenue in 2013. It did, however, spend a lot on fundraising, reporting that just 21 per cent of its budget went to cleft-lip and -palate surgery for children in developing countries in 2012 while 88 cents out of every donated dollar went to fundraising costs.

In a statement to the Financial Post following the revocation of Smile Train Canada’s charitable status, a spokesperson distanced the U.S.-based organization from the Canadian one.

“It is important to know that Smile Train Canada was a stand-alone, separate organization from Smile Train, Inc. in the United States,” Shari Mason said in an email. “It is Smile Train Inc.’s hope that a new organization will be founded in Canada run by a fully engaged Canadian Board of Directors that we can partner with to advance our efforts of providing life-changing surgeries to children born with clefts worldwide.”

Of course, there are many legitimate and well-meaning charities that manage to pull in large amounts of donations on a shoestring. But MacDonald, the CEO of Imagine Canada, said some are so concerned with keeping salaries and overhead costs low that they scrimp on important things like transparency reporting.

“I think there are organizations who worry constantly about the public perception as it relates to costs of administration, overhead and fundraising,” he said. “They might be better served to engage in conversations about why having the backbone infrastructure… is in the best interests of the cause and the mission.”

Charities that spend lots of money on compensation can also run into trouble with the CRA. The tax agency has policies preventing the provision of undue benefits, personal benefits or compensation that is beyond fair and reasonable.

Etienne Biram, a spokesperson for the CRA, said 77 charity audits since April 2014 have uncovered undue benefits, with three of those 77 involving concerns related to unreasonable salaries. She said the CRA considers industry standards, job descriptions, past non-compliance and other factors when determining whether a salary is unreasonable.

Rather than seeing more enforcement from the CRA related to compensation, Bahen said she would like to see donors vote with their dollars.

“I would like donors to be much more active, not passive,” she said. “Make your own decision. But start thinking for yourself and start thinking critically.”

Methodology

Maclean’s analyzed 583 Canadian charities with revenues over $2 million that are also studied by Charity Intelligence. For all financial data except salary ranges, we used Charity Intelligence’s figures, as opposed to data from charity tax returns. Where possible, Charity Intelligence uses data from audited financial statements, which means the figures have been vetted by two independent parties.

Charities must report the salary ranges of their 10 highest-paid employees to the CRA. This information is not typically reported in a charity’s financial statements, so we relied on 2016 tax return data to identify the salary bracket of the highest-paid employee at each organization.

We divided the charities into groups by operating costs in increments of $4 million. Within each group, we compared how charities perform on a variety of financial and transparency metrics based on the salary of the highest-paid employee at each organization. We found each group had a salary bracket where charity performance started to decline, which was at least $100,000 above the median for the group or less than $80,000. The exception was charities with operating costs greater than $20 million, where only extremely low salaries appeared to affect performance.