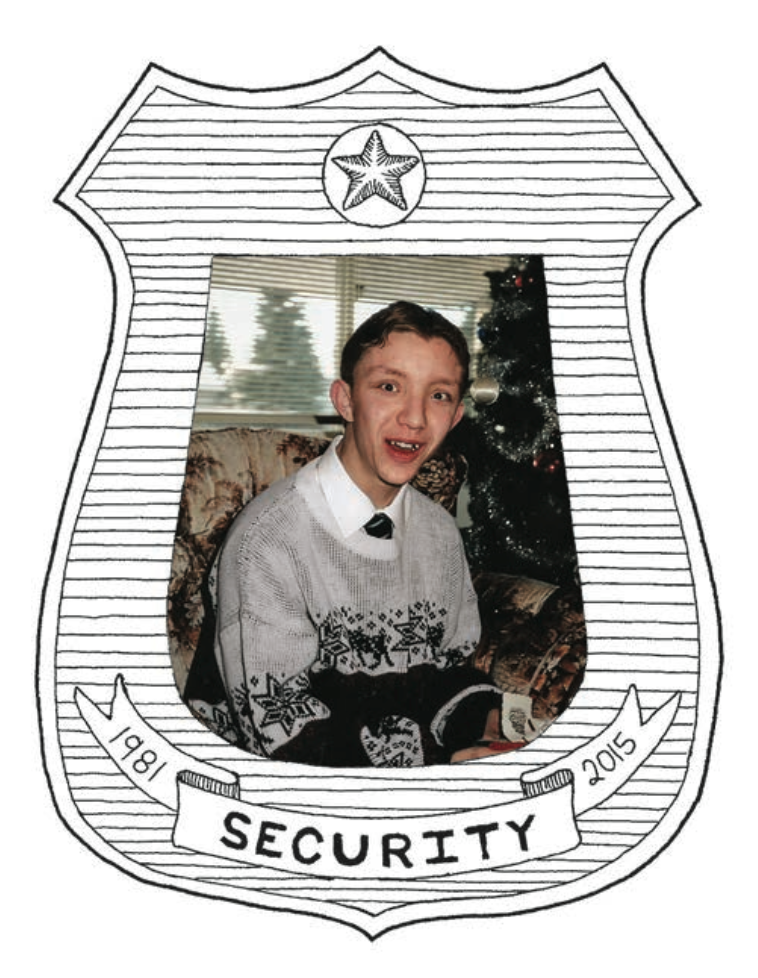

Curtis Allen Nadeau, 1981-2015

After a liver transplant at the age of five, he became national news. He dreamed of becoming a police officer and living a normal life.

Share

Curtis Allen Nadeau was born in Calgary on March 28, 1981. His mother, Kim, was 18 when he was born and his biological father was not involved in his life. Immediately after his birth, doctors knew something was wrong. “Curtis was jaundiced. It just never went away,” says Kim. At three months of age, he was diagnosed with biliary atresia. Potentially fatal, the disease blocks the ducts that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder. Curtis’s growth was stunted and the whites of his eyes and skin were yellow with jaundice, as he made numerous trips to the hospital for blood transfusions and vitamin D injections. At 11 months, surgeons performed a procedure to remove the damaged ducts and to drain bile into his intestinal tract, but the operation failed.

Curtis Allen Nadeau was born in Calgary on March 28, 1981. His mother, Kim, was 18 when he was born and his biological father was not involved in his life. Immediately after his birth, doctors knew something was wrong. “Curtis was jaundiced. It just never went away,” says Kim. At three months of age, he was diagnosed with biliary atresia. Potentially fatal, the disease blocks the ducts that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder. Curtis’s growth was stunted and the whites of his eyes and skin were yellow with jaundice, as he made numerous trips to the hospital for blood transfusions and vitamin D injections. At 11 months, surgeons performed a procedure to remove the damaged ducts and to drain bile into his intestinal tract, but the operation failed.

Yet Curtis was a “bubbly” child, recalls Kim. “He liked to laugh and smile. He was very inquisitive.” Although he didn’t walk until age two and was very small, “he was very witty, very smart.” The only thing he complained about was constant itching, a result of the bile buildup in his body.

In June 1984, Kim, whose maiden name was Radell, met Robert Nadeau, an administrative clerk in the Canadian military, at a bar. They married in Calgary in February 1985, with the honeymoon lasting less than a day; they had to fetch Curtis from Kim’s parents the next morning. “We connected pretty quickly,” Robert says of Curtis. “I always thought Curtis was an awesome human being. He smiled a lot, though he was always in a lot of pain.”

Curtis was three when specialists determined he was a candidate for a liver transplant. “Things got very intense then,” says Kim, as the wait for a liver stretched to two years. In the meantime, Curtis’s story appeared in the Calgary Herald and, soon after, he became national news. Finally, a liver became available after a boy in Windsor, Ont., was killed crossing a highway. On Oct. 14, 1986, Curtis was taken to the Calgary airport by police escort, then flown to London, Ont., for surgery. “Curtis,” who dreamed of being a police officer, “loved that police escort,” says Robert.

The transplant was successful, and five-year-old Curtis’s energy level skyrocketed. For the first time in his life, says his mother, “he actually had rosy cheeks. The yellow left the whites of his eyes. He looked . . . alive.” Curtis returned to Calgary, and his story made headlines for months, as Canadians followed his recovery. During a Calgary Flames game in February 1987, he was the guest of honour and got to mingle with players in the dressing room.

In 1989, Robert was posted to Penhold, Alta. The move away from friends and grandparents was difficult for Curtis. Never growing beyond five foot six, he was bullied. Adding to his health problems, Curtis’s spleen was removed that year. The family—growing after Kim and Robert had two children, Branden and Joshua—moved to Ottawa in 1993, then Wainwright, Alta., in 1996. Curtis grew increasingly frustrated with the cards life dealt him. He began to rebel and “got feisty,” says Kim. One day, he took a girl for a spin in Robert’s car and accidentally drove it off a cliff. The two escaped serious injury.

Kim and Robert decided to send Curtis back to Calgary to live with his grandparents. As a young man, Curtis was determined to live as normally as possible. He worked as a security guard in Calgary, Red Deer and Edmonton. But with weekly trips to hospital for blood work, and bouts of illness that prevented him from working for weeks at a time, he couldn’t keep a job. The anti-rejection drugs that saved him after the transplant were also destroying his kidneys. Between 2001 and 2005, Curtis fell off the family radar. When he finally showed up again, something clearly had gone terribly wrong—possibly a stroke, or a reaction to his medicine or other drugs. He couldn’t look after himself and, in 2011, was placed in a long-term-care facility in Calgary. Still yearning for purpose, Curtis convinced the facility to make him a safety checker. Wearing a uniform he made himself, he checked for locked doors, took disabled residents from one place to another and sometimes joined security on patrols.

Last November, Curtis had surgery to replace a heart valve. He went into septic shock after a dialysis line in his body became infected. He bounced back, but the line got re-infected in July, spreading bacteria to his heart and brain. For several days, Kim stayed with Curtis, holding his hand while he was on life support. “I kept telling him, ‘I love you, Curtis. I am proud of you and everything is going to be OK.’ ” He died on July 7. He was 34.