Does anyone care about fashion anymore? For so-called ‘influencers’ it’s a hot topic.

First-class travel tickets, six-figure salaries and luxury goods—for Canadian fashion influencers, business has hit an all-time low

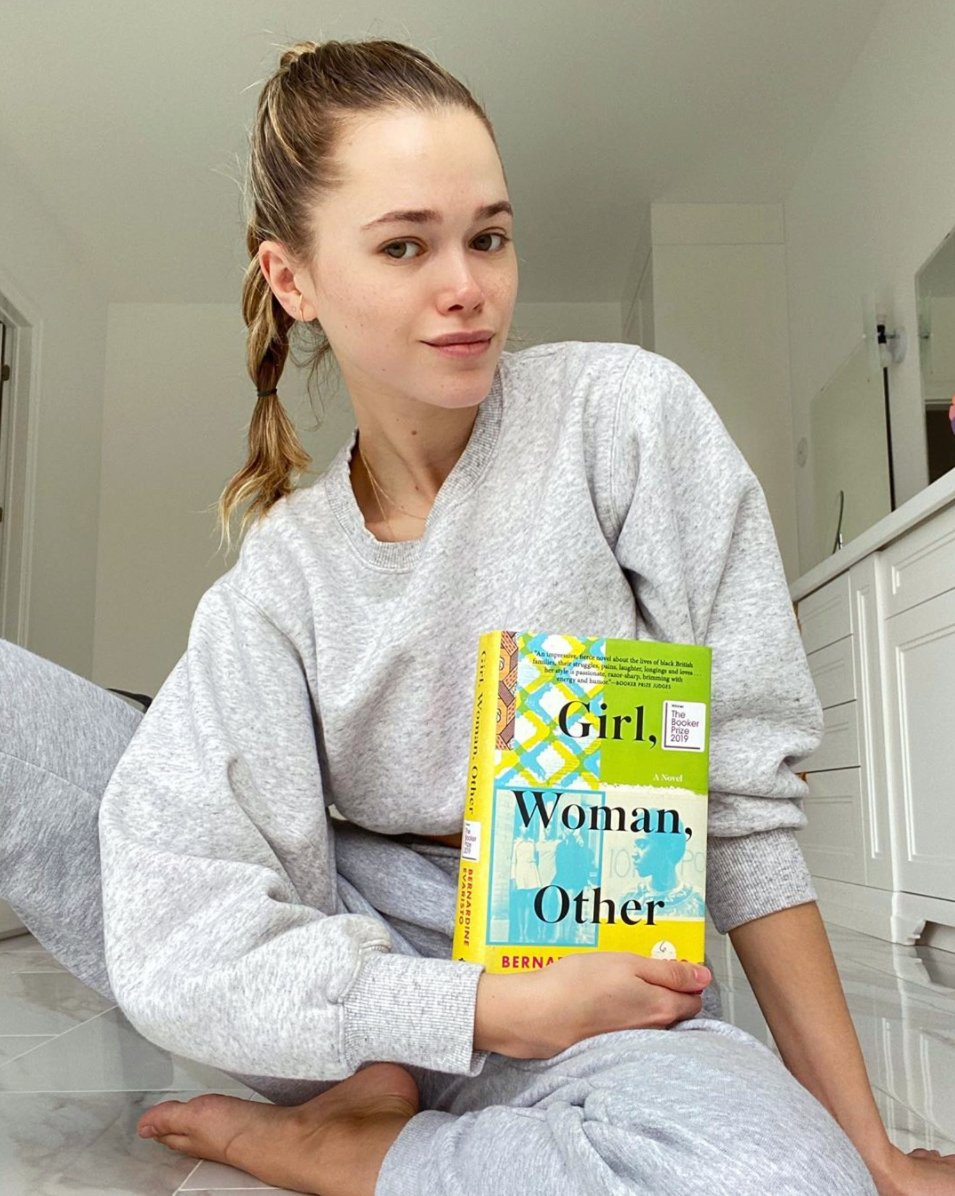

Lansky says her follower count is stable but people are reaching out for more than brands (Courtesy of Jillian Lansky)

Share

This time last year, fashion influencer Jill Lansky was on a first-class flight to South Korea. The trip was sponsored by Seoul-based Amorepacific, one of the world’s largest beauty and cosmetics companies. For the benefit of her Instagram followers (she currently has 119,000), Lansky, 32, documented what she wore: a Ganni leopard print maxi dress, an Alexander Wang fanny pack and Nike Air Force 1 Sage Low sneakers.

In a recent video entitled “How to Look Chic at Home,” she starts by saying, “I’ve gotten a few requests for a loungewear video, so I thought I’d show you what I’m wearing.” She stands up. “Surprise! It’s s–tty sweatpants.” While cute loungewear videos are indeed making the rounds on social media, Lansky isn’t buying. “The only fashion I really care about right now is the personal protective equipment that doctors are wearing,” Lansky says. These are not just words: Lansky is married to an ER doctor who is working on the pandemic’s front lines in Toronto.

When lives are at risk, the “lifestyle” category smacks of gallows humour. In 2019, influencer marketing was a global industry with an estimated value of US$8 billion. But now, in the midst of a global pandemic, even some fashion influencers aren’t that interested in fashion. Management consultancy firm Bain & Company predicts that the global market for luxury goods will shrink by 25 per cent this year alone. Are we done with aspirational content? Have we moved on from caring about $300 cashmere sweaters, Dior throw pillows and picture-perfect lives?

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-xGfOWDadm/

“There are some people who definitely wouldn’t be upset about our downfall,” acknowledges Shannae Ingleton Smith, a Toronto-based lifestyle influencer who also manages other personalities through her agency, Kensington Grey. She worked in advertising for 10 years before turning her Instagram feed, which boasts almost 56,000 followers, into a full-time job. Before the coronavirus, Smith’s followers saw her sporting Away luggage inside the Fairmont Royal York (#gifted) or posing in the latest gown from a collaboration between Italian haute couture designer Giambattista Valli and H&M. It’s common for an influencer with an audience of this size, Smith says, to make nearly $200,000 a year from brand partnerships. And in industry parlance, anyone with under 100,000 followers is a micro-influencer. At the higher end, Jeffree Star, a Los Angeles makeup vlogger with 16.2 million followers, made a reported $18 million in 2018 through brand sponsorships, YouTube ads and, eventually, a makeup line of his own.

But since early March, the daily inquiries in Smith’s inbox have trickled almost to nothing, and contracts for her or the influencers she handles have been paused or cancelled. A campaign for the opening of an Old Navy location at Toronto’s Eaton Centre? The mall is mostly closed. A hair care brand offering an all-expenses-paid trip to Coachella plus a six-figure payment for a few posts? The festival is postponed. May and June are usually busy months, Lansky says, because shoppers are getting excited about the spring/summer season. But this year, there are no trends to look forward to, no high street window shopping to be done. The coronavirus lockdown has taken over everyone’s lives. Smith estimates her own loss of revenue is around 30 per cent.

Milad Sahafzadeh, the president of Imagemotion, a Montreal marketing agency that manages the influencer programs for brands like L’Oréal, Yves Saint Laurent and Zara, says there’s been a huge shift in the luxury sector. Chinese tourists in North America and Europe account for 70 per cent of luxury goods purchases, and the fashion industry has been looking to the mainland for much of its projected growth. But by Milan Fashion Week at the end of February, buyers and press from China had backed out, and Armani, Versace and Prada were among the luxury brands that had cancelled shows launching their spring lines. By March, Italy, one of the world’s fashion capitals, had become a terrifying example of what happens when cases of COVID-19 overwhelm the health care system, and in the U.S., March sales figures in the entire apparel and accessories sector dropped by half. “The first place they will cut,” Sahafzadeh says, “is influencer marketing.”

Consumer behaviour has no doubt changed. How could it not? Unemployment worldwide has soared to record highs. In March alone, one million Canadians lost their jobs. In one week in April, nearly four million Americans filed jobless claims. Never mind those fur Gucci slides; even modest frills are beyond reach as many are already struggling to make rent or mortgage payments.

It’s ironic in this case that influencers may be poised to capture more eyeballs than ever. With lockdowns in effect all over the world, people are spending more time on social media. In the first week of quarantine, Instagram Live views in Italy doubled, and Facebook usage has skyrocketed in the country by 70 per cent. Connecting with others—even through fashion—has offered an escape from all the death and economic chaos.

MORE: Appearing wealthy on social media has become its own industry

Lansky’s follower count has remained stable, she says, but her Instagram impressions have gone up by 15 per cent. People are reaching out to have more personal conversations, rather than just asking what brands she’s wearing. They write to her about missing the ocean, or sunshine, or the view over Dublin. Her followers know she is married to a health care worker, and she gets a lot of “say thanks to your husband for me.”

There is also the question of how tasteful it is to hawk skin cream or Balenciaga flip-flops during a global crisis. Smith believes that people aren’t wrong in thinking this is a bad time to share fashion posts, but fashion and beauty have always been some people’s lifelines during dark times. In England during World War II, the government recognized the public’s need for sartorial variety—fashion designers were brought in to design the “utility suits” that consumers could buy, at a time when materials for civilian clothing were being rationed.

When entire populations are churning with fear and anxiety, there’s valour in small acts of glamour. “Getting dressed, feeling good about yourself and putting on lipstick—those things aren’t cancelled,” Smith adds.

From a production standpoint, influencers may now have an advantage over traditional fashion media; influencers were already working from home and putting together their content with small teams, and can still reach their audiences while major sporting events, music festivals and other advertising venues are shut down for the foreseeable future. In Finland, influencers have been classed as “essential workers” because of their ability to spread information quickly among younger people—an interview with health experts conducted by Roni Back, a blue-haired vlogger who usually does videos like, “Trying Finland’s HOTTEST snacks!” was viewed 100,000 times in two days.

Some fashion influencers have pivoted to posting more wellness, parenting or food-related content. Valeria Lipovetsky, a Canadian influencer with 778,000 Instagram followers and 1.4 million YouTube subscribers, has started inviting meditation gurus to co-host videos on her channel. Lipovetsky’s usual content is more Lancôme than literary, but she’s recently revitalized her book club on Instagram (and it’s not a fluffy one either: Bernardine Evaristo’s Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other is a recent title). Others have shifted to a different kind of beauty product. After the lockdown started, Smith’s agency booked about $70,000 worth of beauty campaigns. The new clients are brands whose wares are available at drug stores—hair products to achieve that salon look without the salon, DIY kits for nail art without the nail bar.

There are signs, too, that pent-up demand will lead to a luxury bounce-back. When Hermès reopened its location in Guangzhou, China, on April 11, customers bought a record US$2.7 million worth of goods. And while storefronts have closed, online retailing is booming, and marketing dollars could follow.

Longer term, Lansky believes fashion influencers will continue to be relevant in our new economy, but they will no longer be making “haul” videos, showing all the disposable fast-fashion items they bought at Zara. “I think moving forward there’ll be more videos of five or 10 ways to wear the same jeans, or the same blazer, because that will be more realistic for what’s going on,” Lansky says.

That may well be true. But, without the major ad buys from brands, fashion influencers may have all the influence with none of the cash. They, too, may go back to basics: Rather than being VIPs making six-figure salaries, they might once again become ordinary people who want to show you their clothes.

This article appears in print in the June 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Falling out of fashion.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.