The best and worst federal party climate plans, graded

A climate scientist and an economist assign letter grades to the major parties’ plans to cut carbon emissions

(Photo: Artur Widak /NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Share

A thermometer isn’t blue, red, orange—or green. It doesn’t give us a different answer based on which political party we support. But increasingly, today, our perspective on climate change—Are the impacts serious? What should we do to fix it?—depends not on the science but rather on our political ideology.

Climate change is a big problem, a global problem; and we know that our own personal choices—reducing food waste, increasing energy efficiency, flying less often—will only get us a fraction of the way there. It’s true that Canada is responsible for about two percent of global carbon emissions each year. But if you count up all the carbon we as a nation have released since 1900, we’re in the global top 10. Per person, we emit the same amount of carbon as two and a half people living in the United Kingdom, 10 people in Zimbabwe, and more than 20 people living in Yemen today. That’s not fair, especially when you consider that some of the people who emit the least, in the world’s poorest nations, are also the most vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate.

We have the technology, human capital, and resources to reduce our emissions today without facing immediate energy poverty. These factors are what the Paris Agreement calls common but differentiated responsibility: climate change is a global problem, and we as Canadians have a lot to contribute to fixing it.

As a climate scientist, I (Katharine) know that the climate system doesn’t care how we cut emissions: but the science is clear that the faster we do so, the better off we’ll all be. And if we want to meet our part of the Paris Agreement, to hold the increase in global temperature to below 2.0C and 1.50C if we can, we don’t have a lot of time.

As an economist, I (Andrew) have spent a lot of time thinking about how we can cut emissions through climate policies. How you define our action relative to others is subjective, but I like to view Canadian policies through a global lens. If the world acts as we do, would we reach our global goals? Today, that answer is mixed. If everyone in the world implemented our current policies, we’d see significant emissions reductions. But if everyone lived and used energy the way we do, we’d be in much deeper trouble.

That’s why, heading into the election, we were so interested to see our political parties’ proposals for cutting our carbon emissions and preparing for the impacts of climate change on our country. Here’s what we think of them.

The Conservatives’ Real Plan

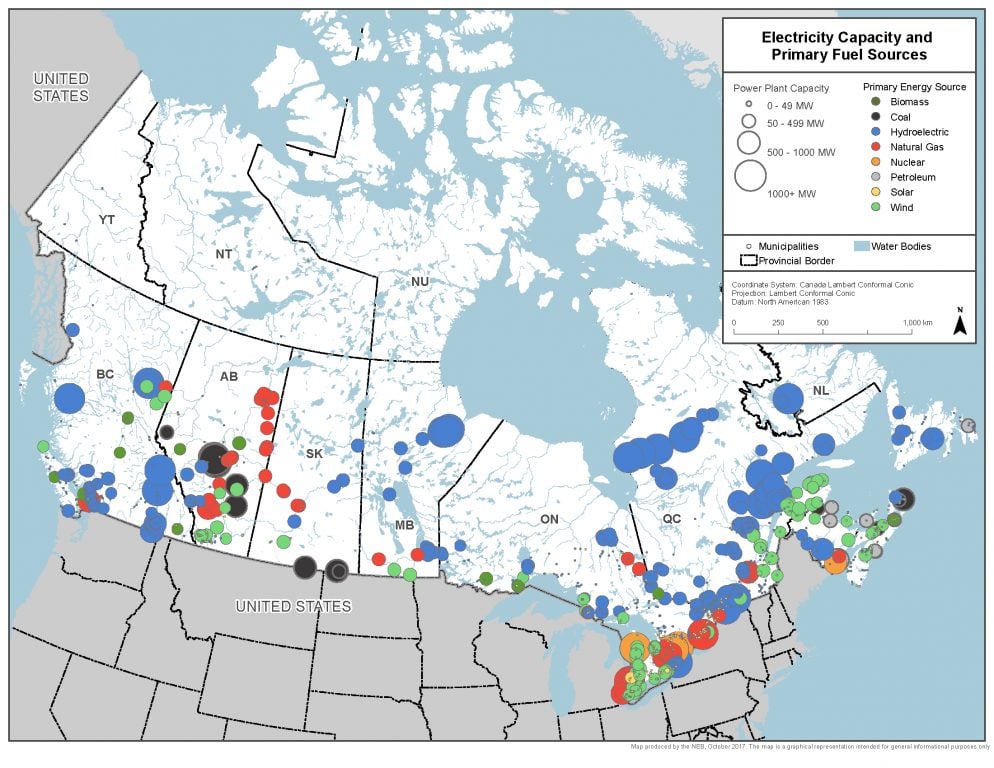

The Conservatives’ climate plan has all the right buzzwords—it talks about green and clean technologies, and emphasizes innovation and protection from pollution. But its actual substance is vague. Very vague. There are some bold promises about how this plan gives Canada the “best chance” at meeting the Paris targets, but there’s not much evidence to back that up. In fact, they’ve been so shy to make commitments that they’re not included on the graph above.

You might think you know what Scheer’s plan is: cut the carbon tax. But that’s not quite true. His plan has one, it’s just hidden. For large emitters, the plan sets emissions limits and forces them to invest a certain amount (How much? No one knows!) for any emissions above that (also unknown) limit. Other aspects of the plan come directly from the Harper government, such as credits for transit passes and home renovations. But both of these policies are relatively expensive per tonne of carbon reduced, since most people who collect government dollars have already planned to make these changes. And the Conservative plan also bets heavily on the idea that we’ll be given an “emissions credit” for shipping natural gas to China, on the premise that doing so reduces their coal use. This is a longshot at best.

The bottom line? Economist Mark Jaccard concluded that, by getting rid of the current carbon pricing system and replacing it with largely optional incentives, the CPC plan is more likely to increase Canada’s carbon emissions than decrease them. David Sawyer and Seton Stiebert of Enviroeconomics separately found that the CPC plan would be insufficient to meet Canada’s Paris target.

What’s good: The plan acknowledges that you can’t expect to win a Canadian election if you don’t have a climate plan.

What’s missing: Policies likely to lead to actual emission reductions.

Grade: D for ambition, F for feasibility

The Liberals’ on-going Pan-Canadian Framework

The Liberals came to power in 2015 on the promise of pricing carbon and collaborating with the provinces. And they’ve successfully priced carbon. The TransMountain pipeline is an albatross around their neck as well: it’s hard to convince people that you’re serious about cutting carbon when you’re funding new ways to transport it (even if those new ways will pay for our green innovation).

But the tax and the pipeline discussions often mask the significant progress that’s been made in other areas. The Liberals are aiming to phase out coal power by 2030, more than 30 years earlier than would have otherwise been the case. They’ve also implemented a clean fuel standard that pushes our fuel producers and importers to reduce emissions all the way from the oil field to our gas tanks. During the campaign, the Liberals have committed to a deeper target—net-zero emissions nationally by 2050—and pledged a $2-billion tree planting program. No matter how you slice it, the Liberals have implemented this country’s first serious, national climate change plan, and they’re looking to build on it.

What’s good: There’s a lot to like in this plan. It builds on four years of experience, it tackles emissions across the economy, and it has measurable targets and ambitious goals.

What’s missing: The Liberals need to prove to Canadians that they can still meet our country’s Paris targets with a new pipeline to the west coast and new liquefied gas facilities in BC. They’ve adopted a more stringent net-zero emissions target for 2050, but the policy path they’ve outlined won’t get them to their goals.

Grade: B for ambition, A for feasibility

The NDP’s Power to Change Plan

The NDP’s plan is ambitious. It argues firmly for meeting Canada’s obligations consistent with a global 1.5oC climate change target rather than the less ambitious (but still challenging) 2.0C target that underpinned the Paris Agreement. They plan to do so through an emphasis on expanding training and education for clean energy jobs, along with investing in zero-carbon housing and transportation and eliminating Canada’s fossil fuel subsidies which, according to the IMF, average around $220,000 per second at the global scale.

Here’s the problem, though—the plan doesn’t explain how they’re going to cut Canada’s emissions 40-50 percent in the next 10 years. It’s also unclear how they’re going to navigate the already tricky issue of provincial versus federal jurisdiction. Not to get too wonky, but if Jagmeet Singh is going to argue that provinces should be able to veto a federally approved pipeline project, it’s hard to understand how he’ll be able to impose a wholesale replacement of a province’s electricity generating assets in 10 years when, unlike pipelines, electricity actually is provincial jurisdiction. Further complicating their plan is the fact that a lot of the subsidies they’ve pledged to remove are provincial tax policies. Plus, the labour wing of the NDP might be swayed by the talk of green jobs, but their pledge to remove competitiveness protections from carbon pricing will increase the challenges faced by industries like refining, steel, fertilizer, and other operations with union workforces.

What’s good: The NDP pledges to keep carbon pricing and sets deeper 2030 goals than the Liberals have today, with a focus on jobs and clean energy.

What’s missing: The details on how exactly they’re going to cut carbon this quickly—and if their support base is negatively impacted, the pushback could be strong. They also need more serious consideration of federal versus provincial responsibilities.

Grade: A for ambition, D for feasibility

The Green Party’s Mission: Possible

As you’d expect, the Green Party is informed and honest regarding the extent to which our economy will have to be transformed in order to meet Canada’s most ambitious climate targets. Their plan also goes into some detail regarding how this transformation might be achieved. However, the proposed target, a reduction of 60 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, implies a 4 percent average reduction in emissions per year. In recent history, emissions have only dropped that fast during the global financial crisis. How likely is it that they can realize their ambitions?

Here are just three examples of the challenge posed by their 2030 goals. First, the Green plan calls for the phase-out of all fossil fuel power—not just coal-fired power—in just over 10 years. Our electricity sector is already very clean; but replacing 20 percent of our electricity generation in a 10-year span (80 percent for Alberta, including plants integrated into oil sands and petrochemical plants) in an area that is solidly within provincial jurisdiction is not going to be easy. Second, the plan also pledges to rebuild the electricity grid linking Canadian provinces with more extensive interties to support renewable power. The regulatory and interjurisdictional wrangling over such a plan could take 10 years in and of itself. And lastly, it aims for 100 percent EV sales by 2030, a goal not quite as ambitious as Norway but which would still require a very rapid transition of the fleet and charging infrastructure. It’s doable, but it’s going to require more than just car sales: charging infrastructure and grid upgrades will be required in spades to support such a change.

What’s good: The plan sets strong overall goals that track with the most ambitious Paris targets, and directly links its goals to specific policies and sectors of the economy.

What’s missing: A realistic path to achieve these goals, given the logistical and legislative challenges facing the country today.

Grade: A+ for ambition, C- for feasibility

Conclusions

The Liberal, NDP, and Green plans all propose to cut carbon emissions: but only the NDP and Green plans aim to meet the more ambitious targets of the Paris Agreement in the near term. However, their ambition is also their greatest challenge: how will such deep cuts be achieved so quickly? The Liberals have the experience to know how big a challenge it is. They’ve acted in line with their promises in the last election and brought in significant new policies. The Conservative plans may actually make the situation worse, not better.

So what’s our choice? Given the four parties’ plans, we can pick between those that offer strong ambition but lack realistic implementation strategies; realistic policies with less ambition; or weak policies that match a lack of ambition. For us, practical policy beats ambition without a viable plan; and anything beats a plan that’s not worth the paper it’s printed on.

Katharine Hayhoe is a Canadian atmospheric scientist. She’s a professor of political science at Texas Tech University, where she is director of the Climate Science Center.

Andrew Leach is an energy and environmental economist and is an associate professor at the Alberta School of Business at the University of Alberta.