He stole their hearts. Then their money. Meet the women trying to catch him.

His hard-knocks childhood and high-paying job were fake. But multiple Canadian women say what a prolific romance scammer took from them is very, very real—and they want vengeance.

(Illustration, Dorothy Leung for Chatelaine)

Share

Like most middle-aged women dipping a toe back into the dating scene, Jodi got on Tinder because her friend convinced her to. They were hanging out, drinking wine. It was a few weeks into 2018 and Jodi hadn’t been on a date in more than 23 years. Having recently gotten out of a difficult marriage, she was in the process of moving on with her life—she had bought a new house and lost a bunch of weight. When she wasn’t stressing over her long-term financial security, she was feeling optimistic and open to new possibilities. Her profile mentioned her love of camping and kayaking and included a link to her favourite country song: “Meant to Be.”

The first guy she met was nice, if not exactly her dream man, and things petered out after a couple dates. She remembers swiping right on Andy’s profile a few days later—he was totally her type in a baseball hat, with a little bit of scruff and good teeth. (“I always look at teeth,” says Jodi, who is now 50 and works as a health information analyst.) She was sitting in her home office in West Kelowna, B.C., when she got a message from him: “I like your profile.” Turns out they had the same favourite song, which felt promising. They met at Starbucks that afternoon and engaged in the typical first date chit-chat. She talked about her career, her dog. Andy told her that he was moving back home to Canada after having spent the last decade in Vietnam. He was an engineer on offshore oil rigs and had apparently done well for himself. Now he wanted to slow down, do some travelling, enjoy this stage of life with someone who wanted the same things. He was figuring out where he wanted to settle down and buy a house, which is why he was in Kelowna. He told her his name was actually Andre; Jodi started calling him Dre.

READ: How Canada became the ‘crown jewel’ of smuggling destinations

Their second date was a movie the very next day. On date three, he came to her place for dinner and they talked for hours about their similar life experiences. He had also gotten out of a troubled marriage, and had grown up with parents who were addicts. They discovered they both hated seafood and loved Mexican. He showed her photos of his fancy condo in Vietnam and his KTM motorcycle. That night, sitting together in her living room, Dre told Jodi he was falling for her. Big time. “Everything he said was exactly what I wanted to hear,” says Jodi (who asked us not to print her last name). Dre was super affectionate—something she hadn’t experienced in years. The first time he went to hold her hand, she was caught off guard, and when she explained that her ex had never done so, he said—wait for it—that he would never let hers go. He met her mom and some of her friends and everyone thought he was wonderful. One of her closest friends has a daughter on the autism spectrum who is generally non-communicative, but Dre was able to bring her out of her shell. “I remember my heart just exploding,” Jodi says. “That was the moment where I thought to myself, ‘Wow, I think I might really love this guy.’ ”

They started to plan their life together. Dre would have to go back to Vietnam to get his money, much of which, he explained, was in gold bars. They would go together, he said—sort of like a honeymoon. First, though, he was going to take a job delivering water to oil rigs in Edmonton. It would just be a few weeks, and the money was great, he told Jodi. Then he asked if he could borrow $500, so he could pay for the recertification required to take the job. Jodi wasn’t totally comfortable with the idea, but Dre had a story about how he couldn’t access his own funds and he promised to pay her back. A single gold bar was worth three times that much, and he had dozens. “I’m doing this for our future,” he said. And at the time, she believed him.

Romance scams are on the rise. If you happen to be a single woman over 40 with a social media account or dating profile, you probably know that already. Recently I was chatting with a friend who fits that description; she told me that weeding out scammers is just another reality of dating these days, right up there with fielding dick pics. (“There are the gross guys who want to turn you into a blow-up doll,” she said. “And there are the ‘nice’ ones who just want you to send them money.”) If she’s exaggerating, it’s only by a bit. Of course, con men (and women) have been faking love for financial gain for centuries. But like many forms of fraudsters, phony Romeos are thriving in the digital era, where you don’t even have to meet your mark in person—or live on the same continent—to take them for all they’re worth. According to the most recent numbers from the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC), romance fraud cost Canadians $26.7 million in 2018—that’s more than any other form of fraud in terms of monetary losses. It’s also an extremely low estimate: The CAFC and the FBI believe that only between five and 15 percent of fraud victims contact the authorities, meaning the actual damage is far greater, both from a financial and psychological perspective.

“People have so much shame around being conned,” says Lisanne Roy Beauchamp, a spokesperson for the CAFC. Unlike a lot of crime, she says, the attitude with fraud is often less “you were victimized” and more “you fell victim.” Given the highly personal nature of romance scams, it makes sense that this particular subclass of scamee may experience the stigma most acutely. Admit it: If you don’t have a personal experience with these types of crimes, you probably harbour some unflattering opinions about the women who fall for them. They must not be very smart or are extremely reckless or just so desperate for a man that they’re willing to overlook the obvious. In reality, this is not the case, says Monica Whitty, a psychologist at the University of Melbourne, who has published papers on romance scams and cyber security. “Those myths are actually part of the problem,” she says, since they can create a false sense of imperviousness.

READ: Put down your phone and make time for the relationships in your life

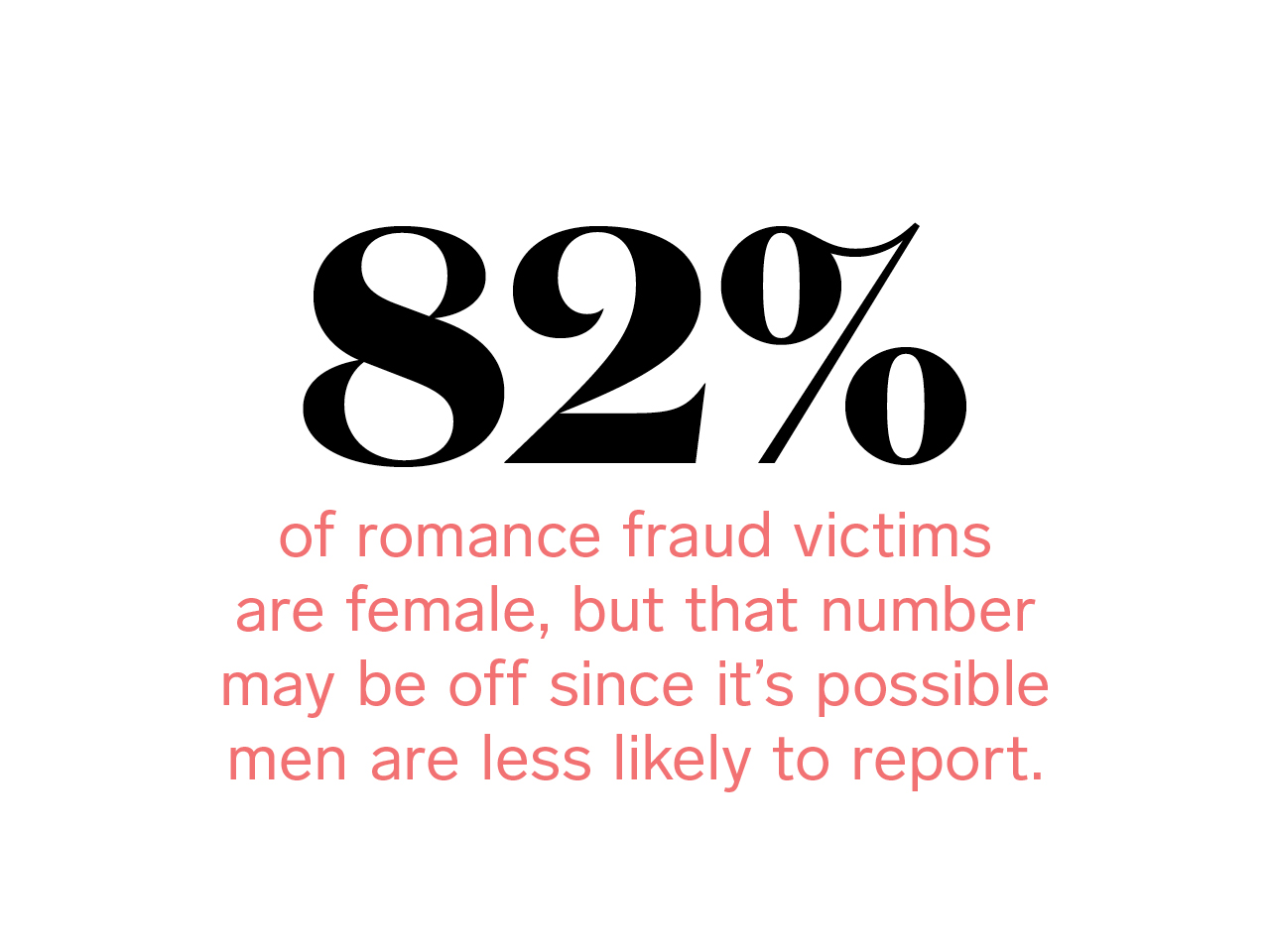

Under the right circumstances, almost anyone can fall prey to romance fraud, but the most common victims are well-educated women in their late 40s, 50s and 60s. (The FBI estimates that 82 percent of victims are female, but that number may be off since it’s possible men are even less likely to report.) They tend to be trustworthy, prone to impulsivity, community-minded and, yes, romantic.

Consider the hugely popular Dirty John podcast (and follow-up TV series), a true story that brought a lot of attention to this type of crime in 2017 and 2018. The victim was the founder of a successful interior design firm. She was close with her daughters until her scammer, John Meehan, took steps to isolate her. “What people don’t understand is how the victims in these scams are manipulated and groomed. For the criminals, this is their job and they are extremely good at it,” says Roy Beauchamp. In most cases a fraudster will start with “love bombing,” either online or in person. The technique—flooding a person with affection and attention to fast-track intimacy and build dependence—is also used in cult recruitment strategies. Mirroring—reflecting a person’s experiences, likes and dislikes—is another effective tool for creating the illusion of having found one’s “other half.”

This is the other way that social media has changed the romance scam racket. To a con man, your Facebook page provides an invaluable cheat sheet: a years’ long record of your interests, values and personality, including the organizations you care about, the politics you subscribe to, your hobbies and favourite TV shows. So suddenly you’re not just meeting some guy—you’re meeting a fellow right-of-centre Christian and outdoor enthusiast who also loves dogs or basket weaving or your favourite country song.

Jodi and Dre had been dating for a month when he left to take the job in Edmonton. He told her he would miss her every moment he was gone. A few days later, he called to say he’d had chest pains, and a doctor told him he should return to Kelowna to recover. Looking back, Jodi believes this was just another layer of manipulation. “My dad died of a heart attack, so he knew that was a thing for me,” she says. Dre came back and planted himself on her couch. Everything would be fine with the job, he assured her. He had subcontracted the first part to one of his guys, and was still earning a cut. When he returned to Edmonton about a week later, he was in touch constantly, inundating Jodi with emailed copies of invoices and time sheets and getting her to input the information into an Excel document. Which is exactly what these guys do, says Whitty. “From a psychological perspective, we’ve only got so many cognitive resources to process new information.” By flooding a victim’s brain with random (and useless) details, scammers create a scenario where you’re more likely to miss what might otherwise read as red flags.

Shortly before Jodi was expecting Dre back in Kelowna, he called to say he was in trouble over unpaid back taxes. He had a big cheque to cash from the Edmonton job—a little more than $49,000—but if he put it in his account, the government would claim it. Without the money, he couldn’t pay his subcontractors. They wouldn’t be able to go on their trip. There was one possible solution, he said—not immediately, and almost like it had just occurred to him. Maybe he could have his employer make the cheque out to Jodi, and they could deposit it into her account instead. Jodi questioned whether this was legal; Dre’s answer was that pretty soon their names would be on the same cheques anyway. Wasn’t that what she wanted, too?

They were on FaceTime when Dre e-deposited the cheque into Jodi’s business account, and got her to transfer him $19,500. To this day, she doesn’t understand why her bank didn’t put a hold on such a large deposit. She doesn’t remember anything looking suspicious, but she admits she may have been distracted.

It was the Easter long weekend, and that same afternoon, Jodi was flying to Vegas for a wedding. For three days, she spent time with old friends and family, danced and got tipsy. And, of course, she told everyone about her new boyfriend, who was taking her on a trip to Vietnam in two weeks. (She had already booked the time off work.) “People said I was glowing,” she recalls. After she got home, she drove to the grocery store. Dre would be back in a few hours, and she wanted to have dinner ready. At the checkout, her debit card was declined. A second card didn’t work, either. She called a friend who agreed to send her some money. While Jodi waited, she started connecting the dots. And her stomach started to sink. When she got home, she sat down at the computer and brought up her banking information, which confirmed what she already suspected. Dre’s cheque had bounced, leaving her nearly $20,000 in overdraft. Between that and the money she had lent him for work expenses and accommodations, she was out $45,000. Her dream man was a con man. And he was gone.

On the same Easter 2018 weekend that Jodi was in Vegas, Rosey (who asked that we use a pseudonym for safety reasons) was boarding a train in Vancouver. The 48-year-old nurse and wellness professional met “Andre” in the bar car one night, while having a drink with some women she had met on board. He was confident and gregarious—he talked about working on oil rigs in Asia, and how he had made a fortune on some well-timed real estate investments. Now, he wanted to enjoy life. The group hung out a lot during the four-day train ride, and when they got off in Toronto everyone exchanged emails and phone numbers. Rosey was visiting family who lived in southern Ontario. The next day she got a text from Andre. He was just a short drive away, he said, as if the whole thing was a happy coincidence—maybe they should get together for a coffee? They met at a Starbucks in the lobby of the Sheraton where he said he was staying.

Rosey was going through a rough patch in her marriage at the time. She was also in the middle of a career change and had travelled to Ontario to visit her aunt and uncle after her cousin had died tragically. Andre had his own sob story about how his parents were addicts, how he lived on his own as a teenager. They were walking around downtown when he got his wallet out and showed Rosey his driver’s licence photo, which he said he hated. Later, as he was getting out of her car, he started slapping at his pockets. Wouldn’t you know it, the wallet was missing! His ID, credit cards and thousands in cash were gone, he said. This was a big problem, because the rest of his money was in Vietnam. He would have to cancel his cards, file a report with the police and figure out where he was going to stay for the night. That was the first time Rosey lent Andre money, paying for his hotel room before driving back to her family’s place.

Over the next few days, Andre made a big production of talking on the phone with the police. He said he would have to go back to Toronto to sort things out with his bank; Rosey lent him money for the bus. Two nights later, she went to the casino with her brother, and won $5,200 on the slots. Andre called shortly after and she told him about her winnings. He was calling, he said, because he had decided to come back to see her. “I can’t stop thinking about you,” he said. When he “got back” (because it’s possible he never left), they headed to a nearby jazz bar. He told her that he had never met anyone like her before. He loved the way her mind worked. He understood that she was going through a tough time, but what if he could make her troubles disappear? He offered to pay off her half of the mortgage so that they could get away. He had a boat that was just sitting in the Caribbean. She could work from her laptop while they lived like one of those couples in a Freedom 55 commercial. As they toasted her windfall, Rosey allowed herself to imagine the life Andre was describing—even if she was the one paying for their drinks.

Rosey and Andre spent three days and two nights together in southern Ontario, all on her dime. When she returned to B.C., he texted her several times a day. He would come to see her soon, but first he needed to fly to Singapore to meet with his accountant and then to Vietnam to get his gold. She wired him funds to pay for his travel visa. She paid for his bus fare from Toronto to Montreal—he had to fly out of Montreal, he explained, because the flights out of Toronto went through the U.S., and he wasn’t allowed into the States because he had taken the rap for his ex’s DUI charge. He always had a detailed story and the receipts to back it up. Later, he texted her photos “from Vietnam”—one of his condo, another of a bed covered in stacks of American bills. He had her money and would be home soon. At this point, Rosey had lost a little under $7,000.

She gets that this all sounds crazy. “I can’t even explain it. It’s like you want to take care of him because you believe he’s going to be taking care of you later. I was confused, but I was intrigued.” Looking back, she says the experience was “like being in a trance.” That is more or less an accurate assessment, says Whitty. “Part of being in a trance is being focused purely on one thing, which is why romance scammers work to isolate their victims.” They also seek out individuals who are already isolated. A Federal Trade Commission survey from 2013 found that participants who had experienced trauma—a death, a divorce, a stressful career incident—in the previous 24 months were more than two-and-a-half times as likely to have experienced fraud than those who had not. Rosey was dealing with all three.

It was only once she was back in B.C. that her brain started to sort everything out. One night she had a dream and woke up with a very strong sense of what was going on. She texted Andre: “I know what you’re up to. I’ve figured you out.” The number was out of service; his WhatsApp had disappeared. Along with any other traces of the man she thought she knew.

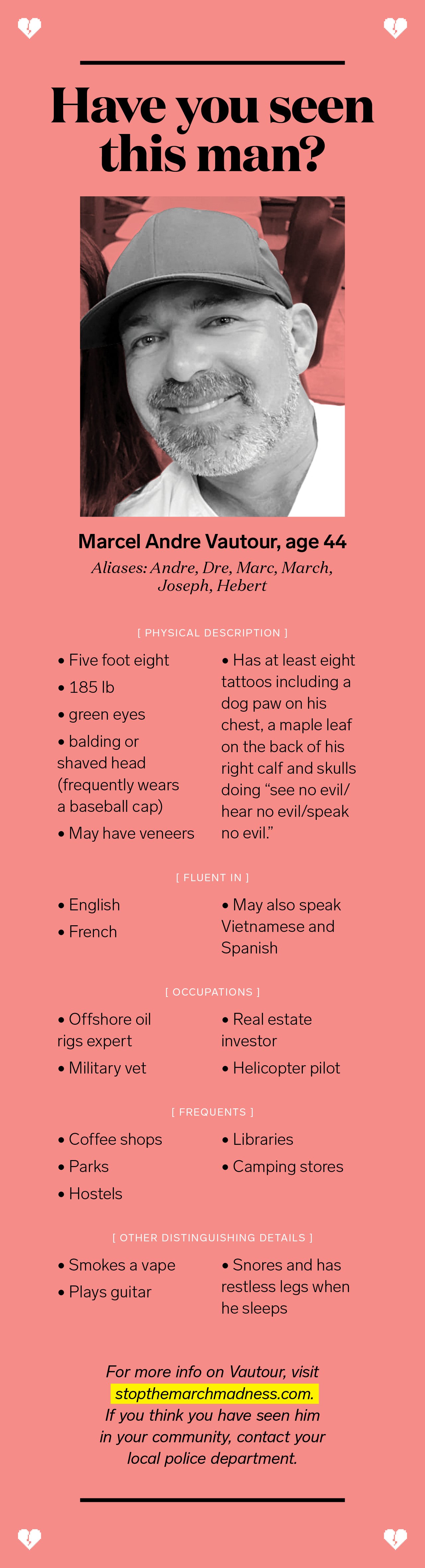

So who is Marcel Andre Vautour? According to his driver’s licence (or one of his driver’s licences), he was born on September 25, 1975. He has at least three siblings, none of whom responded to messages I sent them. Between 2001 and 2008, he was in a common-law relationship with a woman with whom he has three kids; she claims Vautour destroyed her credit by making purchases on her cards and opening cellphone accounts in her name. It’s likely the hard-knocks back story he gives his victims is largely an invention. According to a friend who knew Vautour in grade school, he grew up with a pool in his backyard.

Police records on Vautour go back at least 24 years. While romance scams appear to be his specialty, other allegations and charges against him include credit card fraud, identity theft, possession of goods obtained by crime over $5,000, obtaining by false pretense and auto theft. He has mostly escaped prosecution, but in 2005 he did receive a suspended sentence of one year’s probation in Quebec for credit card fraud. In 2009, he served a six-month conditional sentence in Victoria, followed by two and a half years of probation, for fraud. There are (or have been) arrest warrants for him in Quebec, Winnipeg and New Brunswick—and it’s likely there are more.

The fact that romance fraud is almost never handled federally plays a key role in how scammers like Vautour are able to evade capture by skipping from one jurisdiction to another. Explaining why they do what they do is a little more difficult. Obviously there is the financial motivation, but despite what we see in the movies, your run-of-the-mill grifter is not living like Leo in Catch Me If You Can. “Think of these individuals as having a parasitic lifestyle—when they have a gracious host, they do well. Otherwise, they may be experiencing adversity,” says Simon Sherry, a psychology professor at Dalhousie University who studies various forms of personality disorder. Vautour seems to fit the description: When he isn’t scamming, he’s often holed up in hostels or the Salvation Army. His victims say he has faked illness just to stay overnight at a hospital. They also say he is extremely good at fixing things, including cars and electrical systems. Which begs the question: Why not earn a good living as a mechanic or an electrician? “That’s assuming there is a choice being made,” says Sherry, who has no specific knowledge of Vautour. In general, he says such individuals exhibit traits like remorselessness, social deviance and an unwarranted sense of superiority from an early age. “There is often this sense of, ‘What kind of a sucker would work nine-to-five?’” he says.

In a lot of ways, con men like Vautour and Dirty John’s John Meehan are relics, even outliers, in the new scammer economy that takes place almost exclusively online. According to the CAFC and the RCMP, the majority of the complaints they hear relate to mass-market romance scams: fraudsters who play a numbers game, sending out thousands of messages a day on social media and dating sites—to see who bites. Often attached to larger criminal organizations, they use scripts and work in groups so that the dashing military officer or rare gems trader you think you’re dating is actually a bunch of different people who specialize in various stages of the con: the initial contact, the seduction, the big ask. In most cases, the relationship will escalate quickly and then suddenly there is an emergency: your guy is stuck at the border, his sister needs surgery. The CAFC gets reports all the time from women who head to the airport to meet the love of their life, only to return home humiliated—and cleaned out. And still a scam may continue; the guy will make up an excuse for why he didn’t arrive, or he will admit that yes, this started off as a scam, but now it’s true love. Concerned relatives and friends often call the CAFC, saying that the victim can’t or won’t believe what seems obvious—which simply reflects the power of the manipulation.

For Jodi and Rosey, finding each other was an important step in breaking the spell. The two women met on Facebook after Rosey came across an account Vautour had created while he was with Jodi. After exchanging messages, they started talking on the phone and found that the similarities in their stories were glaring. Both had heard tall tales about gold bars and fancy homes, both had seen the same photo of the bed covered in American cash. It was surreal and also therapeutic, says Jodi. “It’s one thing to tell yourself that it wasn’t your fault—these guys are predators. But meeting Rosey it was like, ‘Okay, here is a smart, capable woman who fell for the same thing.’” Investigating Vautour became their shared passion project. They would check in every few days, giving each other assignments: Jodi traced the phony cheque that he had deposited into her account. Rosey spoke with members of Vautour’s family in Quebec and New Brunswick. They learned a lot about their scammer, but nothing about his whereabouts. “We had almost given up,” says Rosey. “And then we heard from Andréa.”

Andréa Speranza is a 50-year-old divorcée who reminds me of a no-nonsense Toni Collette character. When she met Vautour at a Tim Hortons in Halifax (three months after he had scammed Jodi and Rosey), he was going by March Hebert. She wasn’t looking for a man at the time, and she certainly didn’t need one. Andréa is a fire captain (one of the first women to hold the position in Halifax) who, in 2006, founded Camp Courage, a program that encourages teenage girls to consider careers as first responders. She loves dogs and paddleboarding and corny movies—information I learned from speaking with her, but it’s also readily available online, if you happened to be looking.

It was her friend who first started chatting with Vautour that day in Timmy’s. He mentioned that he was a big outdoors guy and had recently bought 300 acres nearby (but not too nearby) in Digby, where he was building a facility for at-risk youth. “By the time he left, my friend was like, ‘Oh my god, could this guy be any more perfect for you?’” Andréa remembers.

They ran into each other a few days later at a local park and campground—a community hangout where Vautour was living. He showed her his fancy trailer (which was not actually his fancy trailer), and said he was staying there to help out his stepmom (who was not actually his stepmom). Andréa obviously didn’t know this at the time, and everyone at the park was constantly smiling and waving at him. “Of course, I’m thinking he must be a good guy.”

Their first date was a walk in the park; Vautour casually mentioned that his Crohn’s disease sometimes held him back from physical activity. He was extremely attentive and an amazing listener. About a month in, he asked her if they were boyfriend and girlfriend. (Andréa said she wasn’t much into labels, but quietly felt excited about the future.) When Vautour said he had a medical emergency relating to his Crohn’s, she lent him $1,500, then $500 more when it turned out the medication he needed was more expensive than he thought; then another $2,000 for a second dose. He couldn’t access his own money, he said, because his backpack had been stolen. He claimed he spent a day in the hospital recovering from the emergency, but Andréa was working a 24-hour shift at the time so she had no way of knowing.

They both worked a lot. Most days Vautour would text photos to demonstrate the progress he was making in Digby. They would have dinner at her place and he would constantly be taking calls from contractors. “He would be on the phone arguing about the price of a telephone pole!” she says, laughing now at the brazen specificity of his deceit. Andréa has been reading a lot since she learned the truth about Vautour. Malcolm Gladwell’s Talking to Strangers taught her about truth default theory, which is essentially the fact that humans are programmed to believe that other people are telling the truth, particularly if they happen to be idealistic and moral themselves. Looking back, she sees how the stolen backpack and the unproven medical claims were warning signs, but in the moment her brain just didn’t go there. “What seems crazier—the idea that he had his backpack stolen or that every single thing he ever told me was a lie?”

When Andréa thinks back on the things Vautour used to say to her, she feels sick. ‘You’re my soulmate,’ ‘I can’t take my eyes off you,’ ‘I’ve never wanted anyone more.’ Which again, in hindsight, feels a little scripted. But she wasn’t the only one he sucked in. During their relationship, she took Vautour to a number of work events and parties. Everyone seemed to really like him. Even more than that, she says, people were thrilled that she was in a relationship: “They seemed excited, almost relieved, to see me paired off.”

Their relationship lasted for just over five months. During this time, Andréa gave Vautour about $5,000, most of it for medication. The last time she saw him, he was going to Toronto to pick up his dog, Cowboy, from his ex. (Andréa paid for his train and accommodations.) From Toronto, he emailed her a link to the hotel he wanted to stay at; it came from an email address under a name Andréa didn’t recognize: March Vautour. Unsure of what this might mean, she started typing variations of Vautour’s name into Facebook, ultimately landing on a picture of her boyfriend with a single word written across it: BEWARE!

“I’ve heard from women in similar situations at least six times just in the past month,” says Suzanne Edmundson, a private investigator in Vancouver. The number of calls she gets about romance scams has tripled over the last few years, both in terms of inquiries and actual cases she takes on. The reason for the distinction is that a lot of the time, there is nothing she can do. Telling people there’s no recourse is horrible, she says—especially because they’re often bawling and have lost their life savings. “The way I see it, these people have been lied to enough.”

The scams where Edmundson is able to help tend to be the ones like those involving Vautour, where there has been an actual in-person relationship, albeit a fraudulent one. If the scammer has used a real name (or has a lot of online aliases), she can run a background check and hopefully find a criminal record and track them to an address—perhaps even locate assets. Then, their victims can serve them with a small claims charge. This may or may not cover the full extent of the loss—in Ontario, for example, small claims max out at $35,000—but it’s often the best of the three available options, the other two being civil or criminal charges. Victims of romance fraud can (and should) make a complaint with the police, but actual criminal charges are rare. Numerous victims and experts I spoke with say that just getting the authorities to take a complaint seriously can be a challenge. “I can’t tell you how many of the women I talk to have been laughed off the phone,” says Edmundson.

When Rosey went to the police, she was told that yes, Marcel Andre Vautour was a fraudster with a lengthy record of complaints. But, since she had sent him the money while they were dating, proving criminal activity would be difficult. “With a lot of cops, there is the idea that romance fraud is more of a civil matter—a dispute between two people, rather than a criminal violation,” says Lisa Teryl, a senior civil litigator in Halifax, who has consulted with Andréa.

When Rosey went to the police, she was told that yes, Marcel Andre Vautour was a fraudster with a lengthy record of complaints. But, since she had sent him the money while they were dating, proving criminal activity would be difficult. “With a lot of cops, there is the idea that romance fraud is more of a civil matter—a dispute between two people, rather than a criminal violation,” says Lisa Teryl, a senior civil litigator in Halifax, who has consulted with Andréa.

But this doesn’t really add up. If I donated $10,000 to a phony charity, the fact that I was duped wouldn’t change the fact that a crime had been committed. Why doesn’t the same logic apply here? A representative from the RCMP told me that in cases where there has been a personal relationship between a victim and a fraudster, it often comes down to “he said-she said”—which does a good job of demonstrating the mentality that Vautour’s victims are up against. Sergeant Guy-Paul Larocque, RCMP acting officer in charge of the CAFC, says that in instances where there is “enough meat,” there is the possibility of obtaining a nation-wide warrant or even launching a federal task force. Is there a threshold for the amount of money lost or the number of victims impacted that might qualify as sufficiently meaty, I ask. He says these matters are looked at on a case-by-case basis.

The paradox is glaring: In order to get charges taken seriously, there must be proof of significant damages and multiple offences. But proving that would likely require federal coordination, which only happens when a crime is taken seriously. It’s not just romance scams that come against this hurdle (our legal system is weighted toward jurisdictional governance for all kinds of reasons). And yet, says Teryl, “if this guy was going across the country robbing banks, I’m pretty confident we’d see a more coordinated response.”

The difference, she says, lies at least partly in a historically patriarchal justice system where domestic crimes (read: crimes against women) have often been discounted. Less than 40 years ago, it wasn’t considered legally possible for a person to be raped by their spouse, and even today, emotional pain and suffering don’t get the attention they warrant.

After realizing she had lost her life savings, Jodi spent several weeks in a downward spiral of depression and self-medication. She lost income and feared for her safety. “I wasn’t sure if I was going to survive,” she says. (Some victims of romance fraud don’t. In 2018, a woman in Delta, B.C., died by suicide after she was defrauded of almost one million dollars in an online romance scam that rolled out over two years.) Victims who have been intimate with their scammer must also contend with the feeling of having been sexually violated. Currently, Canadian courts hold a narrow view of the kind of fraud that would override consent; romance scams don’t meet the courts’ criteria. The issue is one of slippery slope. People inflate and lie about their income, background and marital status all the time in intimate encounters, so where do you draw the line?

Which is a legitimate concern, says Janine Benedet, a law professor at the University of British Columbia who specializes in criminal sexual offences. Still, she wonders whether other biases may be at play when assessing the credibility of romance scam victims: “When women make a claim where proving the crime requires that we believe them, there is a historic pattern of skepticism and of questioning their motives.”

Like sexual assault victims, the victims of romance scams often feel blamed for their perceived participation. Rosey says she was humiliated and dismissed by police in a way that felt gender specific: “You’re hoping you’re going to be able to get some justice and essentially what you hear back is, well, you shouldn’t have been wearing that short skirt.”

It was Andréa’s idea to take their manhunt public. In March 2019, she launched “Stop the March Madness Campaign!,” an online publicity blitz with three objectives: to raise awareness about the prominence of romance fraud, to provide support and community to victims and, of course, to catch the dirtbag who did this to them. They got a few tips from women who had been out with Vautour in Toronto, but nothing particularly useful—until they heard from Nikola. The 28-year-old backpacker was visiting Toronto from the Czech Republic on a 12-month work visa and first met “Marc” at a hostel in North York in March 2019. She remembers wondering why a helicopter pilot with a substantial military pension would have chosen such a modest living situation; but everyone there seemed to know and like him, and he told her he was just not a flashy guy. Nikola and Vautour were never a couple; instead he said he could get her a well-paying job working as his assistant. When she mentioned her plan to drive to B.C., Vautour showed her a photo of his beach house in White Rock that he had been meaning to get back to, and offered to come along for the ride. After giving her a (fake) contract, he suggested Nikola get a Canadian credit card and went along to the bank posing as her new employer. Over the next three weeks, Vautour racked up $5,000 in charges on Nikola’s card and stole another $500 by depositing an empty envelope into her bank account.

Soon after they arrived in B.C. together, Vautour had to leave; an emergency, he said. By the time Nikola realized what had happened, she was alone and broke. She spent a few nights on the streets before getting a job at a hostel in Victoria. When she told her new boss what had happened, the woman said that Vautour had worked at the same hostel two years ago. They kicked him out in December 2017 after he was caught stealing from a guest. A few weeks later, he met Jodi.

For Nikola, connecting with Vautour’s other victims was the only thing that got her through that terrible time. “I went to the police and they basically kicked me out of the room,” she says. “Rosey and the other women gave me a lot of support.” And she gave them a good tip: Vautour had bought himself a fancy backpack with her credit card and, knowing him, he would try to sell it. Rosey went onto Kijiji and there was the identical backpack, for sale by a guy in Nanaimo named Marc.

This was in June 2019; by then I had been researching this story for a few months. I was at my mom’s 70th birthday party when I got a text from Jodi: “WE’VE GOT HIM!!! FINALLY!!! WE’RE GOING TO GET THIS GUY!!!” She was in Nanaimo, having made the six-hour journey from Kelowna. Her new boyfriend, Vince, was with her and they checked into a hotel before setting off on their mission. Rosey was also en route.

Jodi and Vince started passing out flyers left over from the “Stop the March Madness Campaign!” They focussed on the types of locations Vautour liked to frequent. At Tim Hortons, a worker said Vautour had been in just a few hours ago. Next, Jodi went to put up posters in the library (where Vautour often went to use the internet), while Vince waited outside. Killing time, he showed a flyer to the guy standing beside him, who responded, “Oh yeah, sure—that’s Marc.” He was living just a few blocks away at the Salvation Army.

At this point, Jodi had spent more than a year fantasizing about coming face to face with the guy who nearly ruined her life. “I wasn’t looking for an apology or anything. I just wanted him to see that he hadn’t broken me,” she says. Just as she and Vince walked through the door at the Salvation Army, she spotted Vautour walking out in the other direction. “Hey, Dre,” she said, cornering him in the reception area. At first, it seemed like he was trying to place her. And then he looked scared. She told him he owed her a lot of money and he (of course) had a story: He had been messed up on drugs when they were together, he barely remembered anything. He was finally getting clean and would pay her back, he said, before getting buzzed into a secure area of the shelter. Jodi called 911. She says a Salvation Army employee told her there were no alternative exits, but according to the police report on the incident, Vautour most likely escaped via a back door. Jodi believes he jumped two stories out of a window. Either way, by the time police got there, Vautour had vanished.

Running on a mix of shock and adrenaline, Jodi barely remembers what happened next. Back at the hotel, she was lying down when she heard a knock; it was Rosey. “I think we just hugged for two or three minutes straight,” says Jodi. It was the first time they’d met in person.

That day in June was the last time Jodi, Rosey, Andréa or Nikola have seen or heard anything about Vautour. They are still in touch with each other and with a community of people (12 in total, so far) who allege that Vautour defrauded them. They would rather not think about what happened, but decided to share their stories in the hopes of drawing attention to what they see as an overlooked crime.

Nikola is still working at the hostel in Victoria, using her earnings to pay down some of her debt each month.

Jodi has been with Vince for 18 months now. She is working through her trust issues and doing her best to put the heartbreak behind her. That day in Nanaimo, when she saw Vautour, her heart was pumping pure ice. But sometimes, she’ll come across a photo of the two of them and she’ll feel a sudden rush of affection. “It’s only for a second. I have to knock myself in the head and remind myself of who he really is.” That part is worse than losing the money, although not as bad as the shame.

Andréa has taken a self-defence course and installed a new security system at her home. For a woman who runs into burning buildings every day, the vulnerability has been the hardest thing to accept. I remind her of how she said everyone was so happy to see her paired up. “That’s what society wants to see,” she says.

Rosey is back together with her husband. When she came clean about what happened, it was a moment of reckoning for their relationship. She doesn’t blame anyone but Vautour, but says that maybe if she had felt listened to in her marriage, she wouldn’t have been so susceptible to his charms. It’s a good point and maybe a key thread to this entire story. Yes, romance scammers are master manipulators who target, groom and exploit innocent victims. But our culture has its own role to play. “Invisible woman syndrome” describes the phenomenon wherein women are ignored after they reach a certain age—by potential employers, by suitors, by bartenders. No longer imbued with youth or fertility or (as Amy Schumer would say) “f-ckability,” we have ceased to serve our biological purpose and are deemed less valuable. And then along comes a person who sees you and appreciates you and promises to make all of your dreams come true. Who wouldn’t want to believe in that?