Assisted death is the new pro-choice

When does life—and a doctor’s duty—begin and end? Assisted dying is dredging up the big questions of the abortion debate, for better or worse.

Share

One Monday night in late February, a woman in her 60s met Dr. Ellen Wiebe in Vancouver to receive her dying wish: a lethal medication. Hanne Schafer had been ravaged by neurological disease since 2013 and was sick of being sick. She and Wiebe had consulted for months about the prospect of dying and how Wiebe could help. Wiebe had researched available drugs, and discussed with lawyers and pharmacists. Now, in a matter of minutes, Schafer was gone. But what happened will not soon be forgotten. Wiebe not only became the first Canadian doctor outside of Quebec to provide a court-approved medically assisted death, she also became the de facto ambassador for the cause. “It felt very good to be able to offer this woman what she wanted,” says Wiebe, “a peaceful death.”

Within a week, Wiebe was already in discussion with two other patients seeking an assisted death, and since then she helped another two patients to die. She has also fielded “lots” more requests, she says, from Canadians in different parts of the country with a variety of afflictions but the same ambition: to reclaim life by choosing their own death. In no short time, Wiebe has encountered what some people would consider a slippery slope of more young and vulnerable people seeking assisted death.

One patient in particular stands out. “He is in his twenties,” says Wiebe, “and it’s non-terminal.” But it seems the extent of his suffering is undeniable. In talking with the young man, Wiebe was unconvinced he meets the criteria for an assisted death, which was decriminalized last year, and has been allowed with a judge’s permission since early January. The patient is still determined to die, though. “He said he will stop eating and drinking,” Wiebe says, referring to the practice of “voluntary cessation of fluids and nutrition” among the sick to hasten death. “And to me, that’s incredibly sad.” For Wiebe—who believes that children and the mentally ill should have access to assisted death too—these cases aren’t a risky outgrowth of allowing assisted death, they are a logical extension.

The young man’s situation illustrates the epic challenges ahead for Canadians as of June 6, when assisted death will become legal across the country without a court order. (Quebec passed its own euthanasia law last December.) That’s when patients and doctors more widely will begin to navigate legal and logistical questions around who can have an assisted death and who will provide one, as well as metaphysical questions about when exactly life ends—with a person’s last breath, or before that, when a patient loses his or her ability to really live.

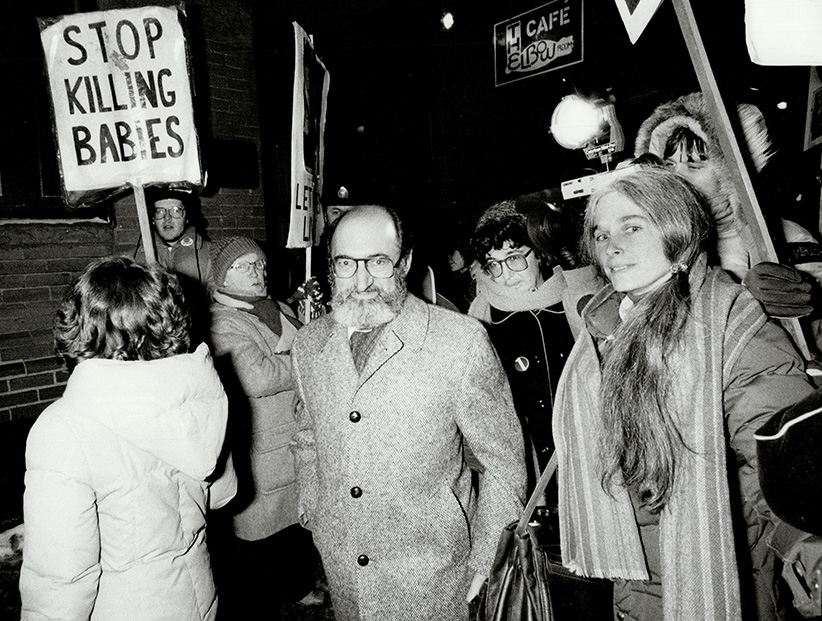

In this way, assisted death is a lot like abortion—and the fact that Wiebe is at the centre seems altogether fitting. Much of Wiebe’s 40-year career as a family physician she has spent doing abortions, including at Vancouver’s first abortion clinic, as well as patient advocacy and pioneering abortion drug research. She’s been called a murderer, her clinic has been doused with blood, its locks glued; she’s received death threats, and her colleagues have been shot. But rather than avoid getting involved in yet another complicated matter, Wiebe has run toward assisted death precisely because of her experience in abortion. Quite simply, she sees them both as “pro-choice” issues. “It’s so important,” says Wiebe, who is also a clinical professor at the University of British Columbia, “that each of us has the right to choose what we do with our own lives and our own bodies.”

The list of concerns over assisted death is a study of the hardest parts of abortion, which was fully decriminalized in Canada in 1988. There are the practical challenges, such as how to avoid a “patchwork” of policies and ensure accessibility across the country, and which drugs are optimal to use, and to what extent they are readily available. And the ethical challenges: what to do about conscientious objection among health care practitioners and institutions; how to navigate questions of religious belief; and of course, who among us should be allowed this medical service and when.

In effect, both issues present a similar philosophical dilemma: how would we respond if our body were occupied in a way we didn’t choose? To what extent can we control what happens to our body—and how much suffering could we endure? It’s a medical question wrapped up in an existential riddle.

The other side of the assisted-death debate is exemplified by another formidable physician but with opposite views from Wiebe. Dr. Nuala Kenny is the founding bioethicist at Dalhousie University in Halifax and a Catholic nun who, for 34 years, was a pediatrician with expertise in terminal cancer. She was also part of the provincial-territorial expert advisory committee on assisted death. As such, Kenny sees this subject from many angles, and “each one is painful,“ she says. “Care of individual dying children has been easier than this issue.” In her own way, Kenny considers assisted death akin to abortion, too: patient self-referral for abortion has “set the stage” for assisted death in Canada. “It has fuelled what I call the market model of medicine. It’s not ‘ask’ your doctor, it’s ‘tell’ your doctor,” says Kenny. “Everyone should understand the seriousness of this. You don’t get a do-over.”

That’s not lost on anyone paying attention, including Wiebe. Especially given what she witnessed in helping that first patient to die a few months ago. Schafer, a 66-year-old psychologist, had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which impaired her ability to move, eat or speak. Her husband and best friend accompanied her to meet with Wiebe. But that night, for the first time in years and for the last time, Schafer had some sense of being in charge. “This is the only time ever that I’ve watched a person be totally in control of their death. She decided where and when and who. She was totally in control, right to the end,” Wiebe recalls, “And that was wonderful. It was beautiful.”

It’s a gripping observation that is bound to provoke. And that might be the point. In a matter of months, Wiebe has emerged within the assisted-death realm as the closest incarnation of Dr. Henry Morgentaler, the late abortion advocate and physician—albeit minus the years of civil disobedience and criminal prosecutions. “I have no concerns whatsoever,” says Wiebe about the legality of her work with patients such as Schafer. “I am doing everything under the law.”

In a way, for her critics as well as her supporters, that may be what’s most astounding of all.

Wiebe understands personally the religious concerns expressed by many people who oppose assisted death. She was raised in a Mennonite family in Abbotsford, B.C., and Wiebe says,“I know my Bible pretty well. I could quote it, no problem.” Her mother was a homemaker, and her father was a teacher who worked for the Canadian International Development Agency, which meant Wiebe and her three siblings spent parts of their childhood in Asia and Africa with them. They were “wonderful people who loved life,” says Wiebe of her parents, and their Christian beliefs were an “important part of their lives for everything and anything.” But as Wiebe moved through adolescence—precociously so, finishing high school at 15—she abandoned her faith. “I lost all my religiosity by the age of 17,” says Wiebe. “It was just part of being in university, questioning and wondering and learning who you are.”

She had always planned to be a physician, but looking back Wiebe says, “Don’t know why. None of us were sick enough to spend time with doctors and we didn’t have any close to us.” From the outset, she focused on women’s health: delivering babies, providing sexual assault care, prescribing birth control—and doing abortions. Wiebe rebuffs the notion that her decision to join Vancouver’s first abortion clinic when it opened in 1988 was a political act: “They needed providers and it was work I liked doing. I wasn’t a very political person. Just taking care of my patients.”

Still, it’s easy to see that from an early age Wiebe has never shied away from expressing her personal convictions, however unpopular. Even her recent habit of using the term “pro-choice” to describe assisted death has made her something of an outlier among those who might cheer loudest for her abortion work. “Some feminists think that’s a terrible word to be using for assisted death, that [it] is only for women,” says Wiebe, laughing as she often does when delivering a wry line. “And of course I don’t.”

For Wiebe, positioning herself as the outspoken promoter and go-to provider for assisted death has been an extension of her life’s work so far. “I recognized there was going to need to be somebody like me who would make sure that access was available,” she says. Over the years, women across Canada have struggled to find a doctor willing to help them end their pregnancy, and Wiebe believes the same will happen with patients seeking to end their life. “It’s so much like abortion because you can have the legal right but if you don’t have providers, you can’t exercise your legal right. And that’s true for assisted death.”

Although Wiebe is at the forefront of the right-to-die movement now, it wasn’t a cause she had considered taking up until last September. That’s when she learned in conversation with a palliative care physician that the majority of those who specialize in end-of-life care will refuse to administer assisted death. Many doctors see it as being at odds with the medical ethos that they should “do no harm”—even if assisted death is legal and requested by a patient. “I was shocked,” recalls Wiebe. “I knew that I had to educate myself.”

What ensued was a crash course for Wiebe and another colleague, who contacted assisted-death providers in Oregon and the Netherlands, where the practice has long been legal. “We travelled to the Netherlands. We did a course in palliative care. We read everything there was to read. We watched all the documentaries,” recalls Wiebe. “We made sure that we had all the knowledge we needed to be ready for Feb. 6.”

That’s when assisted death was supposed to become widely available in Canada. The date marked one year since the historic Supreme Court ruling, which found that sections of the Criminal Code prohibiting “physician-assisted death” infringed on the Charter rights of “a competent adult person who clearly consents to the termination of life and has a grievous and irremediable medical condition that causes enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual.”

The Supreme Court suspended its decision to decriminalize medically assisted death from taking effect until February to give the federal, provincial and territorial governments the option of enacting laws. That deadline was later extended to June. In the interim, several patients, such as Hanne Schafer, have sought exemptions by lower court judges to die sooner. Their identities, as well as the names and motivations of the doctors who helped them, have remained mostly private, no doubt in part because of concerns about safety and stigma.

The sense of fear that hushed abortion discourse for years is now cloaking assisted death. “People judge other people. Some of the patients that I’ve talked to are keeping it a deep dark secret that nobody can find out. They were worried about neighbours seeing the hearse come, which was bizarre because they [would] be dead,” says Wiebe of those individuals who have inquired about receiving an assisted death at home. And “certainly doctors are looking at the issue of stigma and not wanting to be seen as somebody who provides,” she adds. While Wiebe has not received any threats of violence or vandalism, as she has doing abortions, she says, “I’m perfectly aware that it is a possibility.” But she appears unfazed; Wiebe recently established a group called Hemlock Aid to provide consultations to doctors and patients about assisted death, and she has run webinars for medical professionals.

The Canadian Medical Association is attuned to the risks, too. In April, Dr. Jeff Blackmer, vice-president of medical professionalism, was in Kingston, Ont., to talk about assisted death at a meeting open to the public. Planted among the crowd were a few special guests. “There were three plainclothes [police] officers, all armed, in different parts of the auditorium,” recalls Blackmer. Their presence had nothing to do with a local threat; police have been on duty at other CMA events when doctors have gathered to discuss assisted death. So far, there’s been no trouble. “It’s pre-emptive,” says Blackmer of the extra security, and “really very much based on our experience with abortion.” The concern is so significant that doctors interested in upcoming courses will only find out the venue once they’ve signed up. This level of caution is not “something that’s nice to have,” says Blackmer, “it’s something that we need.”

Nevertheless, for many patients and doctors, any concerns about assisted death are outweighed by a desire to at least have the conversation. “The wonderful thing about the choice for an assisted death is that in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Oregon—where they’ve had assisted death for a long time—many people talk about it without doing it,” says Wiebe. “That talk gives them some peace of mind. Somebody gets a terrible diagnosis, ALS or metastatic cancer, and when they know that if it ever gets too bad, ‘I can take the exit,’ then they can face it better.” It’s a strange kind of hope or relief because, of course, says Wiebe, “you still have to die.”

It seems the dread people feel about suffering in death is correlated with their desire to maintain control in life. “The issue that everybody grapples with is loss of function. Can I stand it if somebody’s got to wipe my bum? Will life be worth living when I can’t feed myself anymore? You don’t know that until you get into the situation. But it’s a fear most people have,” says Wiebe. “Not only do they not want pain or vomiting, they don’t want that terrible dependence on others for everything.”

In essence, they want what opponents of assisted death disavow: the power to live and die on their own terms. “There used to be a kind of rhetoric about suffering that had a religious basis—that suffering can be noble, and that [there is] something almost cowardly about trying to avoid or prevent it,” says Wayne Sumner, a philosopher and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, who has written about abortion and assisted death. “That has pretty much eroded away,” he says, “and people now just tend to see suffering as needless. Once you’ve reached that mindset, then you start thinking about ways that you can control for it at the end of life.” The net effect, says Sumner, who served as an expert witness for the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case, is that, “we used to see death as the enemy. Now we’ve come to see suffering as the enemy.”

The experience of suffering is subjective. “It’s not up to anyone else to decide how much somebody is suffering,” says Wiebe. “It is only the person themselves who can decide that.”

On the opposite side of the country from Wiebe in Vancouver, Nuala Kenny recalls how, when she entered medical school in 1962, the profession was already changing in significant ways. The first heart transplant had just occurred, and other developments were under way, including cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, the portable ventilator, and the dialysis machine. “From the beginning of my life in medicine, technology has expanded its scope and possibility profoundly,” says Kenny, who joined the Sisters of Charity–Halifax Catholic ministry that same year. Insofar as assisted death provides an “instant fix” for patients, Kenny says it could be considered a modern technology too. That might explain its popular appeal, as the majority of Canadians polled have long supported decriminalization. “More people in 2016 believe in technology,” she says, “than believe in God.”

To Kenny, the duty of physicians to improve the quality of life through healing is incompatible with assisted death. She is mystified by physicians such as Wiebe who don’t appreciate the contradiction: “If she and I were head to head I’d ask her: in what ways should doctors be using death as a treatment? It is just amazing to me,” says Kenny. “A treatment means you provide an intervention and it is [of] benefit afterwards. If death is a treatment, there [is] no patient after to see whether there’s been a benefit.” While Kenny endorses palliative care to alleviate discomfort at the end of life, there may be some hardship that no doctor can fix. “People suffer all the time, and it has nothing to do with health care issues,” she says. “If you have chest pain, medicine has lots we can do for you. If you have heartache, I have no prescription.”

Scientific achievements have “created the illusion that medicine has the answers to all of our human ailments. We expect that medicine can provide whatever we want, including being able to control the timing and circumstances of our death,” says Dr. Harvey Chochinov, a palliative care psychiatrist and professor at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. The growing emphasis on individual rights and self-determination has also shifted society toward accepting assisted death. “For many, autonomy is synonymous with personhood,” says Chochinov, who led the federal panel on assisted death appointed by the previous government, and is the Canada Research Chair in palliative care. “To not be autonomous is thought of as not being fully human, and therefore as having a life that is dispensable.”

Over the years, Christian opposition to both abortion and assisted death has been much discussed, but many religions have combined voices on this latest issue to release a joint statement that has been endorsed by more than 50 Christian, Jewish and Muslim leaders across Canada. It emphasizes the need for better palliative care, which is supported by most people on both sides of the assisted death debate. The religious leaders share the view that “life is sacred, and we should do nothing on an active level to either hasten or cause the death of someone,” says Rabbi Reuven P. Bulka of the Machzikei Hadas modern Orthodox synagogue in Ottawa, about Jewish theology. “We look upon life as a gift from God, and we are the trustees. Our obligation is to preserve it in the best way possible,” he says, even if the “Canadian consensus would be far removed from such an idea.”

Imam Hamid Slimi of the Sayeda Khadija Centre in Mississauga, Ont. is equally unambiguous. “It is clear for a Muslim, you are not allowed to kill yourself,” he says. “We have a problem with suicide bombers and we tell them: you have no right. You do not own your body, it is God who owns your body,” says Slimi. “Neither the suicide bomber has a right to take [his life], nor the one who is feeling pain.” The imam understands that assisted death is looked upon by many as an act of compassion. “I don’t doubt the intentions are good. People want to show mercy. But there is a bigger picture,” says Slimi, “and that is: How does God see things?”

Foremost on the minds of many religious people is the protection of medical professionals and vulnerable people from feeling forced to participate in assisted death. Kenny says the use of a central referral system—basically a hotline for individuals to request information and access to providers—could adequately balance the obligation of physicians to not abandon their patients while protecting conscientious objectors from having to provide a direct referral for assisted death. But she is worried that religious hospitals, many of which are publicly funded, won’t be safeguarded from providing the service. “I see no appetite for the notion that a faith-based facility could receive the exemptions they have with abortion,” says Kenny, who has worked with the Catholic Health Association of Canada. “What many of us have been saying is this may be the end of Catholic health care,” she says, though she emphasizes this is speculation.

For Wiebe, who is on staff at the Vancouver General Hospital, “the problem is not that we need to be doing assisted death in [religious] hospitals. That’s going to be a very small proportion,” she says. But Wiebe wants patients who wind up hospitalized and faced with a choice between going on a respirator and dying, for example, to have the option of “a consultation with an assisted death provider. And they need it there,” she says. “A Catholic hospital has to allow this, it’s essential.”

On a personal level, Wiebe says she can understand the religious opposition; she has navigated such questions over the course of her career. Wiebe says her parents, who are deceased, were “practical and scientific, well-educated,” and even after she became an abortion provider, they supported her. “As one of my sisters said when my parents were still alive, they might be anti-choice, but they’re pro-Ellen so that’s okay.” This hasn’t changed now that Wiebe has become involved with assisted death. “Our family style is to be warm and loving and avoid certain topics. We do that happily,” says Wiebe. Those who “don’t agree with what I do still hug and kiss me and want to know how the rest of my life is going.”

Over the past five years, the CMA has polled doctors about their views on assisted death, and the results reflect the potential obstacles ahead. “What we know is that about 30 per cent of our members have said that they would be willing to participate in these activities under a legislative framework,” says Blackmer. As modest as that support may sound, it’s an uptick as the topic of assisted death has become less taboo among doctors over time. “As this dialogue became more publicly permissible and we allowed ourselves to have this discussion, we saw a little bit of a shift,” Blackmer says, but “certainly the profession is divided on this, there’s no question.”

The effect of this unease surfaced in the case of Hanne Schafer, who lived in Calgary, where there appeared to be no physician offering assisted death. She located Wiebe only after contacting providers in the Netherlands looking for a lead. “She found me via circuitous route,” recalls Wiebe. “It was hard work.” That Schafer had to then travel to British Columbia, where Wiebe is licensed, to end her life was bittersweet; it was better than going overseas for an assisted death, as other Canadians have done, including Kay Carter, one of the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case who died in Switzerland in 2010. “One hour’s flight is one thing,” says Wiebe, “but 10 hours is quite another.”

In the wake of Schafer’s death, Alberta Health Services announced that, after sending around a survey, it had identified at least 80 doctors willing to facilitate assisted death and had set up a central referral system. As of early May, there were five applications under way, but after June 6, a surge in assisted deaths is expected. “When there’s no longer requirements of a court order I think we’re going to see quite a number of people because [that] process is expensive,” says Dr. James Silvius, the province’s medical lead for preparations for assisted death. “In Oregon there are about 100 a year,” he says, citing its similar population size to Alberta, “so we’re guessing in that range.”

A central referral system in every province and territory will be critical, especially in the early days of assisted death, says Blackmer, adding that the federal government has signalled its support for such mechanisms across the country. Otherwise, he says, “initially it will be next to impossible” for patients to find doctors willing to provide the service. “There will be a very small number of physicians who will be comfortable having their identity made public, and it will be up to the patients to scour the Internet. They’ll be left to their [own] devices.”

But even with a central referral system, there may be access problems, especially for people living in remote or rural areas. “One of the things about Canada that makes it complicated when it comes to health care is our vastness,” says Jennifer Gibson, co-chair of the provincial-territorial expert advisory committee on assisted death and a bioethicist at the University of Toronto. In its report, the group recommended, among other things, that physicians be permitted to consult with patients via Skype. “The distribution of health professionals with expertise and willingness to participate in a lengthy process related to assisted death, it’s not going to be equally distributed across the provinces.”

In fact, among the patients who have reached out to Wiebe since Schafer is another woman from Alberta who Wiebe says couldn’t find a local physician to provide an assisted death—even after the referral system was implemented. Silvius acknowledges one case early on when his team couldn’t help a patient locate a doctor nearby. Since then, effort has been made to overcome this problem by having assisted-death resource teams cover a wider swath of the province, but Silvius acknowledges the logistical challenges ahead: “At the end of the day we’re going to have to have either physicians travel or patients travel. That’s just the reality of the geography.”

There may be another hitch even for patients who are able to access an assisted death: “We have to use second-best drugs,” says Wiebe, because the optimal medications used elsewhere are not readily available in Canada. “It’s not any extra suffering for the patient,” says Wiebe, but they don’t work as fast. The effect is that patients may feel obliged to have an intravenous injection by a doctor, which would end their life in 10 minutes, rather than take an oral prescription by themselves, which would take four to six hours, says Wiebe. She is well versed in the arduous process of obtaining the best medications: In 1998, Wiebe first published research on the medical abortion drug mifepristone and began pushing for its use in Canada; Wiebe says it’s estimated to finally be marketed in September.

The most immediate challenge for assisted death in Canada relates to what the eventual law governing it will look like. Since April, the federal government has hustled to pass controversial legislation that might limit the scope of assisted death to patients whose “grievous and irremediable medical condition” is “incurable” and for whom “natural death has become reasonably foreseeable.” In the near term, it would also prevent mature minors and the mentally ill from accessing assisted death, and prohibit Canadians with conditions such as dementia from using advanced directives to plan for ending their life.

People such as Kenny and even the CMA are relieved by the cautious approach. But many others see these restrictions as unnecessary, out of step with the Supreme Court decision, unconstitutional—and cruel. “I understand why these are lightning rods,” says Jocelyn Downie, a Halifax lawyer and professor at Dalhousie University, and a member of the provincial-territorial advisory group, but “I think we do have to allow it.” Downie has worked on assisted death for more than two decades, including as a member of the pro bono legal team arguing for it. “When you know the decisions that mature minors and [patients] who have mental illness are already permitted to make, you understand why these were reasonable recommendations,” she says.

Wiebe agrees. “There’s no way a child should be forced to suffer more than an adult. That’s completely wrong,” she says. “And if you’re one of those [patients with] treatment-resistant depression, are you supposed to suffer hell for the rest of your life?” Wiebe is equally upset by the case of the young man who plans on ending his own life if she cannot provide an assisted death. Although she doesn’t reveal the specifics of his illness, Wiebe says, “I believe [patients] should have a good death if they choose death. You would want to go to sleep and not wake up, and you can’t do that by yourself easily. I can guarantee you a peaceful end.”

Plans are under way for Wiebe to provide patients with exactly that after June 6. Even if the federal legislation on assisted death doesn’t pass, the Supreme Court ruling will become the law of the land—a far less restrictive one, too. The weight of what’s ahead is palpable, but Wiebe’s convictions don’t falter. “These are people who are going through tragedies, every one of them.” If Wiebe ever loses sleep about it all, she remains undisturbed. “I’m a 64-year-old woman,” she says with trademark wryness. “I’m up at night, anyway, so what does it matter.”

As a family doctor, Wiebe says she’s seen “a lot of death, good and bad.” Her personal experience has left an impression on her, too. “I’ve certainly had loved ones die good deaths and not-so-good. And as you get older, you think about your own death more,” says Wiebe. Insofar as she can imagine her final days, Wiebe anticipates holding the reins to her life for as long as possible. “That doesn’t necessarily mean an assisted death, but I want to be in control, that’s for sure,” she says. “Because I like control.” So if Wiebe is rare among doctors today, in the end she may not be so different from most Canadians.

Editorial note: The online version of this story was updated on May 27, 2016 to indicate that Dr. Ellen Wiebe has completed three assisted deaths so far.