How Nunavut has stayed coronavirus-free as a second wave hits Canada

Nunavut is a rare jurisdiction in North America that has kept the virus away. The territorial government has been lauded for its efforts, but also criticized by residents for taking extreme measures.

Eaton in her Ottawa hotel room, where she is quarantining before being allowed to enter Nunavut (Photograph by Frank Reardon)

Share

Update, Nov. 6, 2020: Nunavut confirmed its first case of the coronavirus on Nov. 6, in the Hudson Bay community of Sanikiluaq

A row of camping chairs lines a section of the Ottawa Airport Residence Inn parking lot, where Inuit elders watch fellow Nunavummiut walk circles around the empty expanse of asphalt. One young mother decides to run laps as she pushes her baby in a stroller. A father of three is trying to keep his kids entertained without straying from the lot.

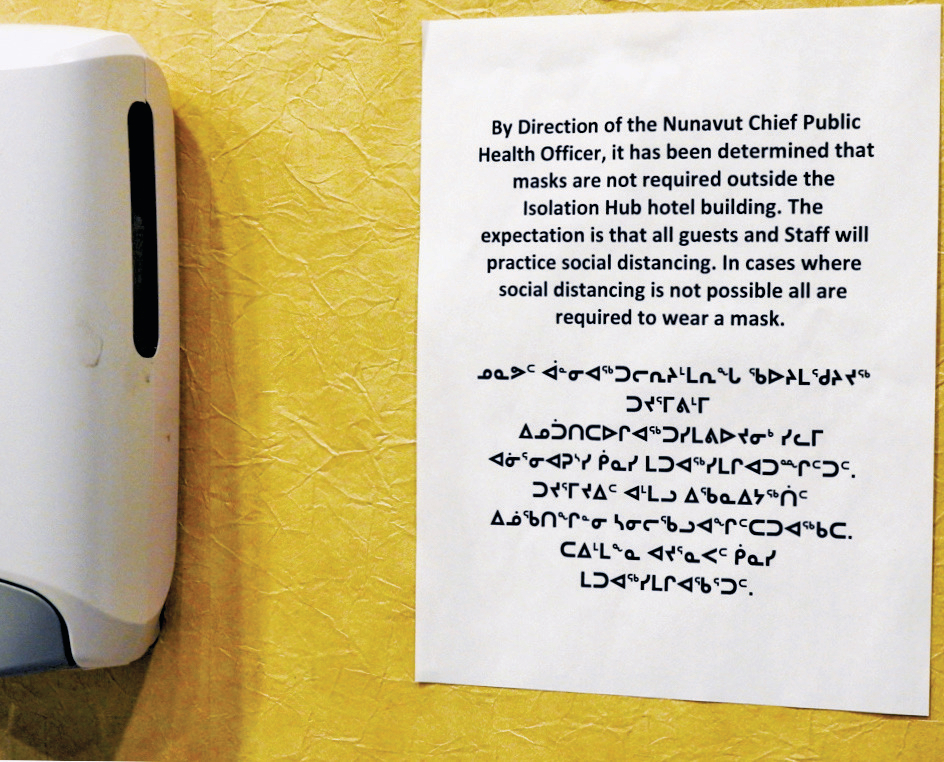

There are security guards on hand to enforce distancing, and more in the lobby of the hotel. And by the elevator. And in the hallway—constant reminders that no one can use the gym, swim in the pool, visit another guest’s room or even hang out in the corridors.

“The parking lot is the only entertainment in town,” says Susan Eaton, who, like the Nunavummiuq mom, spends more than two hours a day walking laps on the pavement. Eaton is set to become Nunavut’s newest resident, but before she can board the plane to Iqaluit for her new job with a marketing and communications agency, she must complete the government’s 14-day quarantine at one of the designated “isolation hubs” outside the territory. Her reward for two weeks of tedium—and “watching way too much TV,” she says—is significantly less concern about the coronavirus spreading in her new hometown.

That’s because there’s no second wave in Nunavut. In fact, the territory is still waiting on the first.

[contextly_sidebar id=”O8CPo6OZal9Fh2xlfOl45Mzlq3H2RpBk”]

Eaton is the latest of about 6,000 people—most of whom left the territory for work, vacation or medical reasons—to undergo the two-week hotel lockdown before being allowed to enter Nunavut. It’s the strictest requirement for entry to any province or territory, entailing six isolation sites across four cities that have cost the territorial government more than $22 million, not including millions spent to maintain two additional hubs for more than 1,000 southern-based construction workers who’ve flown in for building projects.

Still, throughout winter, spring and summer, Nunavut was the only state-level jurisdiction in North America that could call itself coronavirus-free. That distinction appeared to be jeopardy in late September, when several employees at the remote Hope Bay gold mine tested positive for COVID-19, and the results were sent for confirmation at a southern testing lab. Permanent residents of Nunavut, though, could rest assured their communities remained safe, as the mine is isolated and no Nunavummiut are currently on the site.

The government has been lauded for keeping the virus out for so long, but also criticized by residents for the extreme measures it has deployed to achieve the feat, none more stringent than the forced quarantine of locals outside the territory before they are permitted to come home.

“Most people would prefer to be in their own home for 14 days,” acknowledges Dr. Michael Patterson, the territory’s chief public health officer. But with limited access to testing and overcrowded housing, he adds, the hub model made sense for Nunavut: “We needed to be more rigorous and careful to limit the chance of an outbreak until we improve other circumstances, like testing turnaround time.”

The government identified its unique vulnerability back in January: Iqaluit’s 35-bed hospital is the only one in the territory, and many locals must leave Nunavut if they require serious medical attention. Meanwhile, more than half of the territory’s Inuit population live in overcrowded homes, according to Statistics Canada data. “That would be a risk point for the spread of the virus,” says Cynthia Carr, an epidemiologist who previously worked with the territorial government. “It just takes one case to start that chain of transmission.”

Not to mention the singular logistical challenges of testing, tracing and treating potential cases among 38,000 people, who live in 25 small communities scattered across roughly 20 per cent of Canada’s land mass. There are no roads into the territory, and while isolation from the rest of the country helped keep the pandemic at bay, it would pose huge problems if COVID began to spread within Nunavut’s hamlets. “If there is an outbreak,” says Patterson, “the only way we can respond to it is to charter a plane to [fly in more] staff.”

Which is why the territory declared a public health emergency in March despite its zero case count. Bars were closed. Restaurants moved to takeout only. The 2019-2020 school year ended early and a couple dozen low-risk prisoners were released to prevent overcrowding. Restrictions have since been loosened, and school is back in session. Nunavummiut can travel to the Northwest Territories or Churchill, Man., without the mandatory isolation period. But if they go anywhere else, the rule remains.

When Jean Kigutikakjuk suddenly fell ill over the summer and needed an air ambulance lift out of Nunavut, she knew she needed her family by her side. When she was feeling well enough to come home, that meant she’d have to be confined to a single hotel room in Ottawa for two weeks with her three daughters—ages 10, 12 and 14—and her husband, Randy.

The period provided some rare, family-only bonding time, with sports or arts and crafts, Kigutikakjuk says. But after two weeks, the routine had worn thin. The food seemed bland, the security overwhelming. “I really don’t want to go through it again,” Kigutikakjuk says. “After 14 days with your kids and husband, you need a break.”

Absurdly, two days after their return, the family was warned that one of the security guards at their hotel had tested positive for COVID-19. They would have to quarantine again, at home. By then, the kids had already visited friends and attended a birthday party. (They were later told they had been in a low-risk zone and were given the all-clear.)

Given the rigmarole, many residents have rethought their plans to travel outside the territory. A few who were in isolation hubs lost patience, abandoning their hotels and the chance to fly home. Some Nunavut government employees have expressed frustration that, if they leave the territory on a non-essential trip, the quarantine period must come out of their vacation allotments. Nunavut’s lone MP and members of its legislative assembly count among the few who can apply to bypass the requirement, along with a list of essential employees that includes mineworkers. Perhaps sensing hazard in the public mood, the politicians had all reportedly forgone the privilege as of this writing.

Successful though it’s been at keeping the virus out, Patterson says that Nunavut can’t remain coronavirus-free indefinitely; the isolation hubs can’t stay forever. “We have to balance our work to delay the arrival of COVID with the harms it causes,” he says. “We have to change from responding to COVID to living with COVID.”

This article appears in print in the November 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Zone defence is a grind.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.