Sheila Montague on being a COVID-19 contact tracer—back in January 2020

She learned on the fly how to track the virus. ‘Back then, I was making lines on a piece of paper with a ruler to record the temperatures,’ she says. ‘Now it’s so streamlined.’

Sheila Montague. This portrait was taken in accordance with public health recommendations, taking all necessary steps to protect participants from COVID-19(Photograph by Nathan Cyprys)

Share

The first call was scary—“like entering the unknown,” says Sheila Montague. It was January 2020, and she was assigned to case management and contact tracing of the first positive COVID-19 case in southwestern Ontario’s London-Middlesex Health Unit, and only the third in Ontario. “When I heard the test was positive, it was like, ‘What do we do?’ ”

Montague dialled the number on record, but there was no answer—so she turned up at the person’s doorstep. “She was jet-lagged and had turned her phone off,” Montague tells Maclean’s. “She took the news amazingly well. She just asked, ‘What do I do?’ ”

It turned out to be one of the easiest cases she would manage: a student at Western University who had returned from visiting family in China. The woman was asymptomatic while travelling, yet fully aware of the stakes of COVID spreading. She wore a mask throughout her journey, sat far from others and—miraculously—took the names and contact information of strangers on her shuttle bus ride from Toronto’s Pearson Airport to London, Ont. The next day, she woke up with a mild fever and cough, and took a taxi to the hospital—gathering the driver’s contact information, too. Montague checked in with the student every day. “Back then, I was making lines on a piece of paper with a ruler to record the temperatures,” she says. “Now it’s so streamlined.”

The term “contact tracing” was unknown to most Canadians when Montague started phoning up strangers. Within months, health units across the country were scaling up teams of people who learned on the fly about the dynamics of the virus—and about human imperfection. Their work was considered a vital tool that could allow Canadians to get back to something resembling normality. But as case counts rose sharply during the second wave, it proved too fine an instrument on its own. Contact tracers simply couldn’t keep up.

READ: Contact tracers are the new front line against COVID-19

They’ve remained essential, though—not only in curbing the spread of the virus but in lending their ears to those anxious about a positive test result. “At first, people would ask if they were going to die,” says Montague, who eventually shifted out of contact tracing last year. “My job was constantly reassuring them.”

Some people would get upset when Montague told them they had to self-isolate for two weeks. Or that she couldn’t tell them the name of the person with COVID they’d been near: “They’d ask, ‘Then how am I supposed to stay away from them?’ ” Her answer: “Well, you’re going to have to stay away from everybody.”

Suffice to say, her job was more than being a bearer of bad news. She would check for symptoms, log temperatures and make sure those quarantined had access to food and medication. Many have been grateful. The Western student, for one, kept in contact with Montague long after there was any need from a public health perspective. The two became friends and, at one point last year, the student told Montague about passing her driver’s exam. As soon as COVID-19 is in the rear-view mirror, they’re going to go for a ride together.

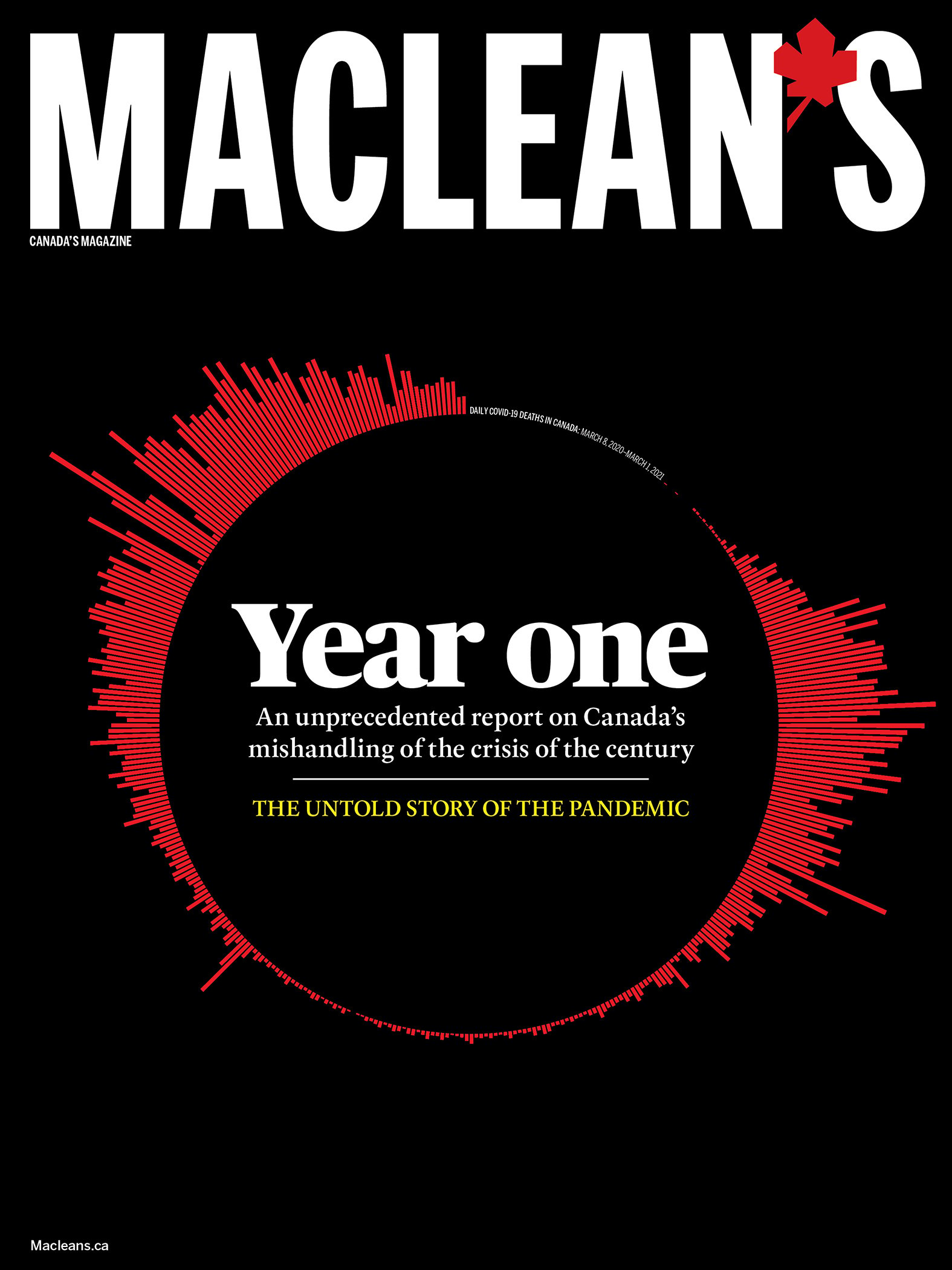

This profile appeared in the April 2021 issue of Maclean’s, where we gave our magazine over to a 22,000-word special report, “Year One: The untold story of the pandemic in Canada.” Read that whole story, and learn why we did it.