Should we withhold child benefits from those who don’t vaccinate?

Our current approach to getting parents to vaccinate isn’t working. Why it may be time to look further afield for solutions

CANADA, Joliette: The Joliette (Centre local de services communautaires) CLSC where the Direction de santé publique invites the population to go to get tested for measles, on February 22, 2015. A 19th case of measles has been detected in the Lanaudière region. The infected person had been to the Rogers shop of Les Galeries Joliette. The Direction de santé publique advised pregnant women who aren’t vaccinated, children under one and persons with a weak immune system who had been to the shop between February 12 and 19 to visit the Joliette CLSC (Centre local de services communautaires). RICHARD PRUDHOMME/CP

Share

A C.D. Howe report released today contains some disheartening information for everyone involved in the fight against preventable infectious diseases in Canada: vaccine coverage is in decline in many parts of the country.

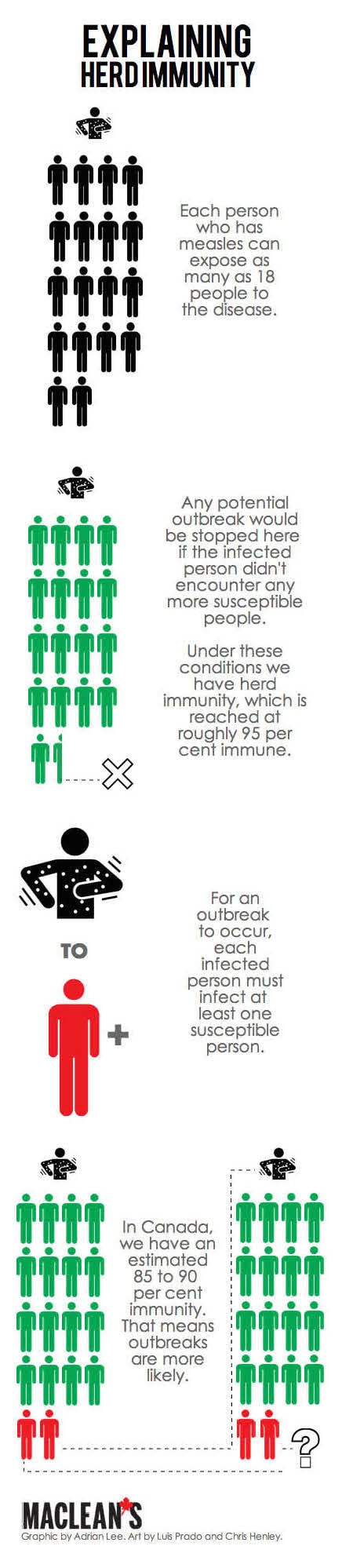

This is particularly unwelcome news given the exponential spread of measles that is once again under way in Quebec. The Lanaudière region, about two hours northeast of Montreal, has seen 119 confirmed cases of measles since the disease was imported last month by a vacationer returning from Disneyland, in California, where an outbreak began in December. An additional 160 insufficiently vaccinated people were exposed to measles in Lanaudière earlier this week when an infected child attended school. The case count is sure to rise.

Related: The real vaccine scandal

So far in 2015 the U.S. has seen more than 170 measles cases; Canada 138. That’s more than all our cases from 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007 combined. The vast majority can be traced to Disneyland.

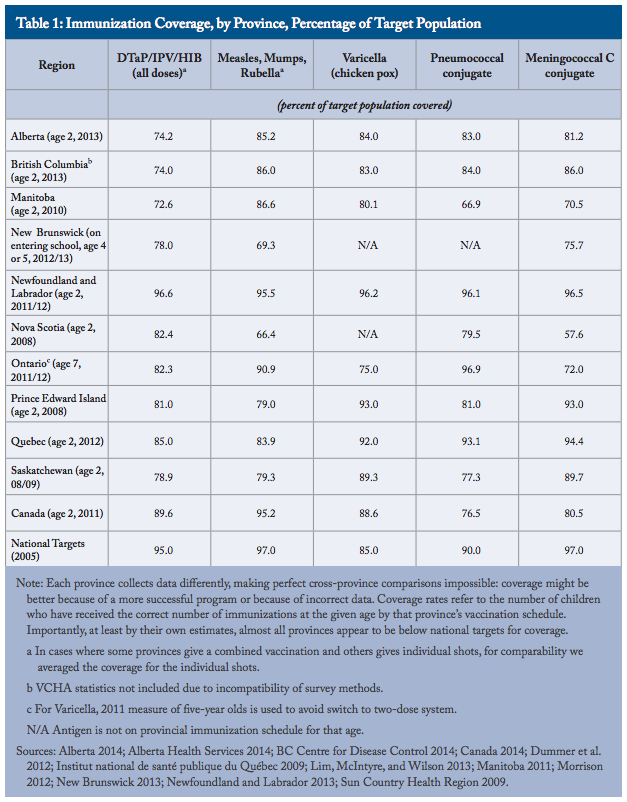

According to the report, the only province that is consistently hitting national targets for five key vaccines is Newfoundland and Labrador; some are falling dangerously short.

Comparing the data across provinces is a bit hard to do, as every province has a slightly different vaccination schedule and its own way of collecting data. Moreover, the newest information available from one region is six years old. “Immunization registries should start at birth. A national system that allows public health authorities and immunization providers to track immunization status would be ideal,” the report says, adding that past failures in that regard have indicated that a network of provincial registries might be the only compromise.

The institute paints the federal government’s phone survey of childhood immunizations as insufficient to identify the specific, regional weak links in our vaccination defences. Outbreaks, after all, always start as a local problem, and under-vaccinated people tend to cluster together.

Nevertheless, some provinces have smart, effective programs. Newfoundland children get their shots during consistent, regular visits from public health nurses, who also administer vaccinations in schools. Written consent is required at infancy, kindergarten, and grades four, six and nine, which gives nurses regular opportunities to address parents’ concerns. Alberta has a somewhat similar nurse-led approach, and vaccine information is collected from birth at community health centres. Reminders and follow-up after that first vaccination appointment are spotty, though, and a large portion of the province’s kids are only partially vaccinated.

Ontario’s strict approach to vaccination of school-aged children—to opt out you need to get an exemption form notarized—is really effective at upping vaccination rates for older children, though rates are far from where they should be. But there’s little to no enforcement of vaccination for kids below kindergarten age. In Ontario, family doctors give most shots, which might not be the best idea because of the high demands on doctors’ time, limited availability of appointments, and the significant population without a family doctor.

From the archives: Why we’re asking for an outbreak in Quebec

No province is doing a good enough job seeking identifying groups at risk; including immigrants, home-schooled kids and, interestingly, children delivered by a midwife, who are less likely to be vaccinated. The report’s authors make a guess that parents who are hostile to the medical establishment—including vaccinations—are also more likely to seek a natural approach to childbirth. Midwives, however, are medical professionals who base their practice on scientific evidence. They don’t generally give vaccines; their care extends only for a short time after birth. Ontario midwives explicitly endorse the provincial vaccine schedule. Getting midwives more involved with vaccination could help reach many families who aren’t currently vaccinating.

The report suggests combining the best elements of all the provinces’ approaches to create one robust immunization system for the whole country; keeping in mind that some approaches, like home visiting, might be more feasible in rural, sparsely populated areas and could overwhelm resources in a big city.

Drastic improvement, however, might require drastic change, and the institute points to Australia as inspiration for future vaccine policy. In that country, child benefits—the equivalent of Canada’s Child Tax Benefit and Universal Child Care benefit—are contingent on vaccination. Australian parents earn an additional Maternity Immunisation Allowance of roughly $120 at 18 months and again at four years old if their child gets every single one of their recommended vaccines. This carrot-and-stick model has done wonders for vaccination coverage—rates for all recommended vaccinations are above 90 per cent, and are recorded in a comprehensive database.

Nothing motivates people to change their behaviour like putting a significant chunk of their income on the line. Requiring shots for child benefits could help reach the lazy, harried or procrastinating parents who haven’t kept their kids’ shots up-to-date. Since research shows that reasoning with anti-vaccination parents is largely a lost cause, the possibility of introducing financial incentives is a proposal worth debating.

The situation in Quebec has been a wakeup call and an indication that it might be time to open up the conversation about a change in vaccine policy. There was an overnight jump in cases this week from 80 to 119—a 40 per cent increase in just 24 hours. Health authorities are now scrambling to isolate the sick and stop the spread, a massive task given the lack of comprehensive data and the amount of catching up to do.

The C.D. Howe report recommends against investing time and energy in getting hard-core anti-vaxxers, including religious objectors, to change their tune. The community at the heart of the Lanaudière outbreak is a small, insular religious group, la Mission de l’Esprit-Saint. None of the infected people have been vaccinated, and it’s unlikely they will be. That’s why it’s doubly important to ensure that the surrounding community is protected. If less than 90-95 per cent of the population is immune to measles, chances are the disease will continue to spread person-to-person.

Don’t be surprised if travel during the upcoming March Break spreads measles out of Quebec into other regions in North America or around the world as people who are incubating the virus travel far and wide for holidays. Even if only a few of the sick people pass the disease on, the outbreak could persist for a long time. Although Lanaudière does not compare to Disneyland in terms of tourist traffic, any measles hotspot can become an infection “sink,” like California has been, seeding further outbreaks all over the continent. During the last Quebec outbreak, in 2011, a single “super-spreader” (one highly social person who was particularly talented at infecting others) was linked to 678 measles cases. There’s nothing—yet—to prevent that from happening again.