How grieving has changed during coronavirus: A funeral director’s experience

‘I realized how important rituals are in response to the chaotic experience of grief. I feel disoriented right now because I’m not able to provide families with those comforts.’

Funeral Director RIchard Paul adjusts a body in a casket. (Photograph by Isaac Paul)

Share

Richard Paul, 65, is a funeral director at Paul Funeral Home in Powassan, Ontario.

I have been in the funeral business since the day I was born. I learned all about this profession from watching my father, who learned from his father, but it wasn’t until I took university psychology courses that I realized how important rituals are in response to the chaotic experience of grief. I feel disoriented right now because I’m not able to provide families with those comforts.

When we experience loss, such as the recent horrific events in Nova Scotia, there is that natural stirring of wanting to help, to alleviate the suffering, to make meaning out of the senseless acts, and give significance to the lives ended. I think we are all coming to realize that virtual activities—although better than nothing—hold just a shadow of the benefit compared to being able to express loss and sorrow when we’re physically together.

Our last “traditional” funeral at Paul Funeral Home was on Mar. 9. All churches have since been closed and the Bereavement Authority of Ontario has instructed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, all funeral activities, whether inside a funeral home or outside at a cemetery, are now limited to 10 people in total. In Nova Scotia, the maximum is five people. In Newfoundland, because they can trace most of the province’s COVID-19 cases to a funeral visitation that happened in March, the chief medical officer of health ordered a complete provincial ban on funerals and wakes.

It’s crossed my mind that I’m at an increased risk of contracting the virus because of my job, but I feel prepared because I worked through the AIDs epidemic in the 1980s. That’s when I started using universal precautions, which essentially means treating each body as if it is infected with a transmutable disease.

Since the restrictions of COVID-19, we have responded to 20 deaths, none of them due to COVID-19. Roughly one-third of my clients opt for immediate cremation and no ceremony, but the rest are having their funeral plans deferred indefinitely or completely cancelled.

Most of the families I have recently served have accepted the limitations imposed upon their funeral activities with resignation and varying degrees of frustration. One family was angry because the restrictions were forcing them to ask: Who isn’t allowed to come to the funeral? It’s a very difficult question and all I could do was reiterate that I’m just the messenger here.

For years, I’ve felt that North American funeral practices are a luxury that people in war-torn or developing countries are not necessarily afforded. I can’t imagine how gut-wrenchingly painful it would be to have my mother or child laid to rest in a mass grave, like we’ve seen in other countries. Even now, we are still finding ways to give all our clients an individualized service.

MORE: Quarantine nation: Inside the lockdown that will change Canada forever

One instance was a lifelong resident of our community, who under normal circumstances, would’ve had a public visitation followed by a Roman Catholic Mass, burial ceremony and reception. None of those happened. Instead, for the first time in my lifelong career in this industry, I had multiple cars out in the driveway of the funeral home so the five adult children and their families could come in separately and spend time with their deceased father and grieving mother. Any celebration of life or memorial ceremonies are indefinitely postponed until the COVID-19 restrictions are lifted.

I’m a certified death educator and the most satisfying part of my job is being able to help people work through their grief. Right now, I feel more helpless than I ever have in the face of families looking broken-hearted, not only by the death, but by their inability to “do the right thing” in memory of their loved one.

Since COVID-19 restrictions prevent us from showing up and supporting each other the way I would normally encourage, for now, I advise people to go beyond platitudes, like “if there is anything I can do, let me know” or “sorry for your loss.” Instead, share a meaningful memory or story about the deceased. On our online memorial page, someone recently wrote a tribute saying how the person who had died meant so much to her because they had both had cancer at the same time. Stories like that really give significance to the memory of the life for the survivors—it’s an added gem in their treasure chest of memories.

After the coronavirus restrictions are lifted, we need to take action to support the bereaved: to give support without being asked; to deliver some food, to take the kids to the park; yo help with the laundry, the yard, the cleaning. We need to give the support that we would’ve normally offered at the funeral.

—as told to Ishani Nath

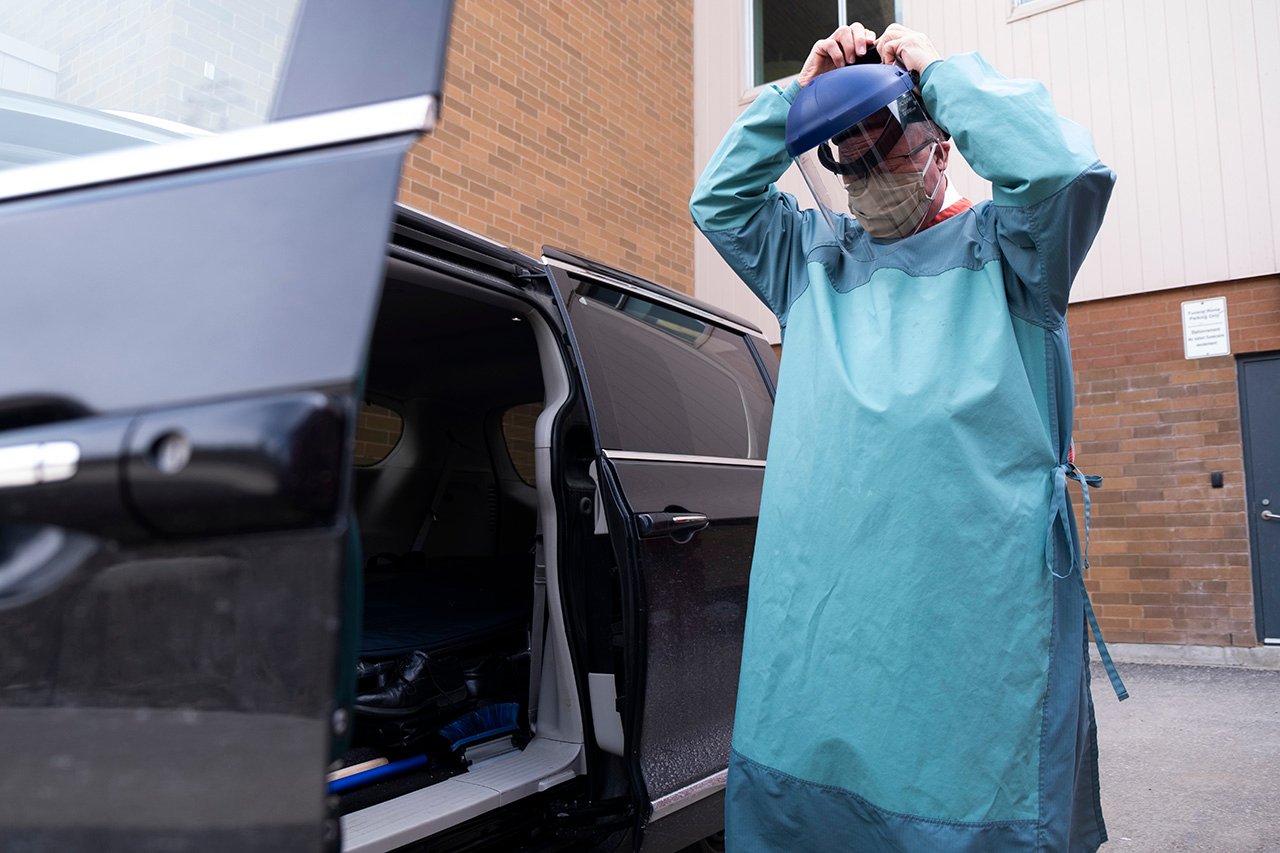

Paul at the North Bay morgue. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he is required to wear extra protection.

“I have boxes of paper masks and I actually don’t have a clue how I’ll get the N95 mask. I’ve been speaking with a supplier in Brampton about masks, gloves and body bags and they told me they could have supplies shipped in about three weeks… I’m hoping I can last until then.”

Paul filling out forms at the crematorium

“There’s a new directive from the Bereavement Authority of Ontario that crematoriums be open seven days a week and that they don’t allow any stockpiling of bodies during COVID-19. As a comparison, I’ve seen crematoriums in the past get backlogged because they stick to three cremations per day on a Monday-to-Friday schedule. Recently, I went to deliver a cremation container and they had no bodies stored because they’re working every day and processing bodies right away.”

Paul storing bodies in the cemetery’s winter vault.

“The winter vault is a building on the property of the cemetery that’s been made to use the natural cold of the winter to preserve bodies until the spring season, when the cemeteries can dig graves again. Right now, we aren’t anticipating a surge in deaths like we’ve seen in other countries. The thought is that if everyone sticks to the rules and regulations, there won’t be an increased need to store bodies because we’ll be able to continue using the crematorium or cemetery as soon as a death occurs. If there are more deaths than I can bury or cremate, we’ll have to use our winter vault until the end of May.”

A burial is being conducted with social distancing put in place

“We started in-earth burials in mid–April partially due to the early spring, which helped thaw the ground, but also because of concern surrounding the government forecasting an imminent surge in coronarvirus deaths. According to the new guidelines, a maximum of nine people, plus the clergy person, are allowed to attend the graveside ceremony and they all must practice physical distancing.”

Paul heading back to his family home

“One of the directions from the Bereavement Authority of Ontario is to treat each body like it is a COVID-19 body, so I’m taking all the precautions I possibly can to protect myself. If I’m protected, then my family is protected.”