Immigration of only the fittest: The cruel biases facing people with disabilities in Canada

Anne Kingston: Heroes do scale walls, but some of those walls aren’t physical ones. People with disabilities face heavy biases in Canada’s immigration system.

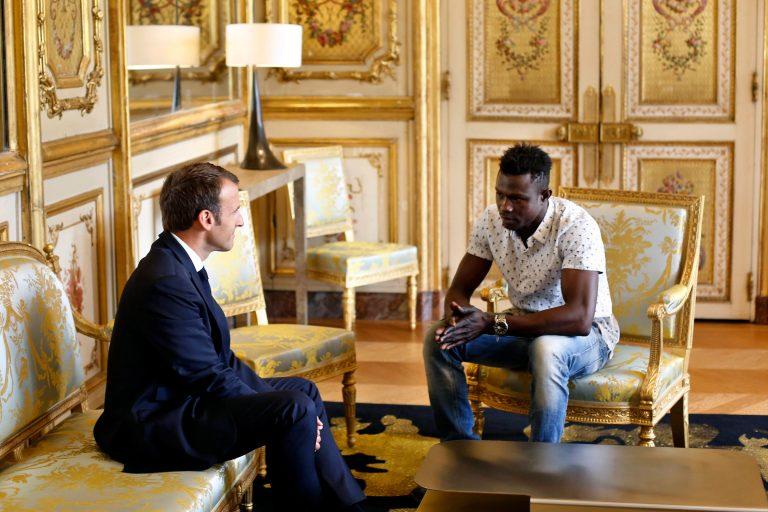

French President Emmanuel Macron meets with Mamoudou Gassama, 22, from Mali, who was living illegally in France who was honored for scaling an apartment building to save a 4-year-old child dangling balcony. (Thibault Camus/AP/CP)

Share

Who could have foreseen that being granted French citizenship only required scaling a Parisian apartment building like Spider-Man to rescue a four-year-old boy dangling from a balcony? But, as we saw, days after 22-year-old undocumented Malian migrant Mamoudou Gassama performed this heroic feat, captured on video in May, he met with French President Emmanuel Macron, who welcomed him to the country. Macron, who’s calling for tougher immigration laws, praised Gassama’s “courage and devotion,” commenced his naturalization procedure and offered him a job as a fireman.

Seeing citizenship granted so quickly to a man who exhibited societal engagement via physical dexterity is the inspiring stuff of cinema. It also reminds us of an uglier flip side: the unconscious biases and systematic discrimination facing people with physical disabilities who can’t scale buildings but who’d be excellent citizens.

After Gassama’s daring rescue, jokes flew that immigration decisions should be made via Hunger Games-style cage matches. They already are, in subtler ways. In 2016, the Trudeau government vowed to overhaul immigration laws that deny people residency based on “medical inadmissibility,” meaning that they or an immediate family member have a disability or medical condition that could place “excessive demand” on publicly funded health and social services. This year, the government loosened medical criteria denying permanent residency and tripled the ceiling on annual health care costs in order for a person to be admissible, to about $20,000.

READ MORE: How universities are helping students with ‘invisible’ disabilities

Disability and immigration advocates criticized the changes as minor and noted that Canada is not compliant with its domestic and international human rights obligations; federal NDP immigration critic Jenny Kwan contends any move short of terminating the policy ignores benefits these newcomers would bring to Canada and frames them as a net drain on the system. In a culture that glorifies “action-adventure” and conflates “strength” with physical might, such biases are predictable. Consider the stream of imagery from the federal government emphasizing its “fitness” and vigour. Justin Trudeau was only taken seriously as a political contender, recall, after prevailing in a boxing ring. Yet Trudeau also recognizes that diversity includes those with disabilities; he named Calgary MP Kent Hehr—rendered quadriplegic* in a shooting before becoming a lawyer—minister of veterans affairs and formed the Ministry of Sport and Persons with Disabilities in 2015. Granted, “sports and disability” is an adjacency destined to summon the feel-good athletic achievements of the Invictus Games or Terry Fox and Rick Hansen. “Ministry of Justice and Persons with Disabilities” is more appropriate.

But politics has always embraced the optics of physical vigour. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who contracted polio at 39 and relied on a leg brace and cane, avoided being photographed with the wheelchair he used in private. President Kennedy hid his back problems. President Obama’s physique summoned gush. Even the way we discuss “disability” focuses on burden, not accessibility. People without disabilities are “able-bodied,” “healthy” or “normal”; those who rely on a wheelchair are “confined” to it. The needs of those with disabilities are often overlooked, evident in the plastic-straw-ban debate or disdain for packaging for pre-cut fruits and vegetables; those with limited mobility rely on both.

RELATED: Breaking down barriers for med students with disabilities

People with disabilities increasingly feature in popular entertainment, though actors with disabilities tend not to get the gig. We’re seeing characters with disability appear without it being a plot point. Yet there’s still a tendency to deify (read: dehumanize) those with disabilities—Hehr’s ejection from caucus for reportedly sexually harassing women was a useful reminder of that fact.

Looking away from disability is also political. After Donald Trump mocked New York Times reporter Serge F. Kovaleski, who has arthrogryposis, a condition affecting the joints, he expressed discomfort over the Olympic and Paralympic Games, calling them “a little tough to watch too much, but I watched as much as I could.” Nazi Germany didn’t like seeing people with physical disabilities either; it started sterilizing them in 1933, then killed them.

Alternatively, the voices of people living with a physical disability can provide an antidote to political and cultural biases. The brilliant Wheelchair Kamikaze blog by Marc Stecker, a former New York City video producer diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, for instance, is a wise, wit-filled and often harrowing account of living with a chronic, degenerative disease; it’s also a profound meditation on what it means to be fully human.

Eleanor Roosevelt called her husband’s disability “a blessing in disguise,” and said it was why he served an unprecedented four terms: “It gave him strength and courage he had not had before. He had to think out the fundamentals of living and learn the greatest of all lessons—infinite patience and never-ending persistence.” It’s a reminder that heroes do scale walls, and that most of these walls are not physical ones.

CORRECTION, June 6, 2018: This story originally referred to MP Kent Hehr as paraplegic. In fact, Hehr is quadriplegic.